It’s hard to think of a single product that’s had a bigger impact on the design world than Adobe Photoshop. Ubiquitous with photo editing and image manipulation, the application turned 25 years old last week.

“There are so many people using and learning Photoshop now who are younger than Photoshop itself,” David Wadhwani, Adobe’s digital media head, tells Quartz. Wadhwani, who joined Adobe through its acquisition of Macromedia in 2005, remembers picking up a copy of Photoshop 1.0 at a local Frys electronic store all those years ago. Then, it came in the form of floppy disks housed inside a special box—the way most software was sold.

Wadhwani took over Adobe’s digital media business unit four years ago. Early into his role, he saw Adobe at a crossroads. The company was profitable, but it was price increases—not new customers—that was driving growth. Meanwhile, productivity software, from Google Docs to Basecamp, was increasingly delivered over the web, either for free or as an inexpensive subscription.

And so, in 2012, Adobe debuted the Creative Cloud, retiring its Creative Suite of software the next year to transition customers over to its subscription service. That meant no more boxed software or resellers, just a link to download.

With a subscription model, Photoshop and other software from Adobe, such as Illustrator and After Effects, became much more accessible, with packages beginning at $10 a month, compared with a one-time fee of $700 for Photoshop alone. For users, the cloud-based infrastructure meant Adobe could push out updates more frequently, and people could sync workflows across devices.

For Adobe, it means more revenue recurring, reducing the company’s reliance on huge, new version launches and convincing its user base to upgrade every couple of years for even more money. Furthermore, the constant connection to the web would also help thwart piracy, a big problem for Adobe. (Wadhwani stresses this was not the company’s motivation to switch to a subscription model, however.)

The move, successfully executed, has set Adobe—one of the world’s largest software companies—up for the current industry realities. (Another aging giant, Microsoft—which has long based its business on software licensing—is now also trying to shift to subscription services.) Of course, it also prompted plenty of backlash. David Hobby, prominent photo blogger at Strobist, called it “the biggest money grab in the history of software.”

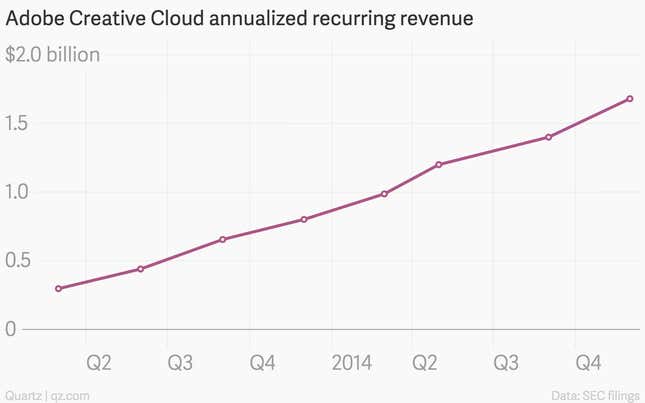

But glancing at Adobe’s quarterly reports, it’s apparent users have adjusted. At the end of fiscal year 2014, Adobe reported $1.7 billion in annualized recurring revenue for Creative Cloud, a 70% increase from 2013. About two-thirds of the company’s fourth-quarter revenue was from recurring sources, up from 44% a year prior. Adobe’s share price has nearly doubled over the past two years.

Ultimately, Wadhwani says the goal is to make Photoshop and other Adobe products more accessible—to “take technology sold to tens of millions of people over the last 25 years and turn that into technology that we can have hundreds of millions of people use over the next 25 years.” For Adobe, though, it means continued relevance as its old business model—expensive, one-time software licensing—is going extinct.