Today Wal-Mart conceded it needed tighter controls over its supply chain so that the factory fire that claimed 112 lives in Bangladesh last month won’t happen again. The world’s largest retailer, though, stopped short of truly taking blame: The factory making Faded Glory clothing was not approved by Wal-Mart, according to the company, but rather subcontracted by one that was.

And Wal-mart’s standards audits of more than 9,000 factories in 2011 wouldn’t catch something like this either. “If a supplier or an agent chooses to subcontract without informing us, then that is a problem,” said Rajan Kamalanathan, the company’s vice president for ethical sourcing, according to Reuters. “We can put all kinds of controls in place, but if they don’t tell us where they’re putting our order, then that is a problem.”

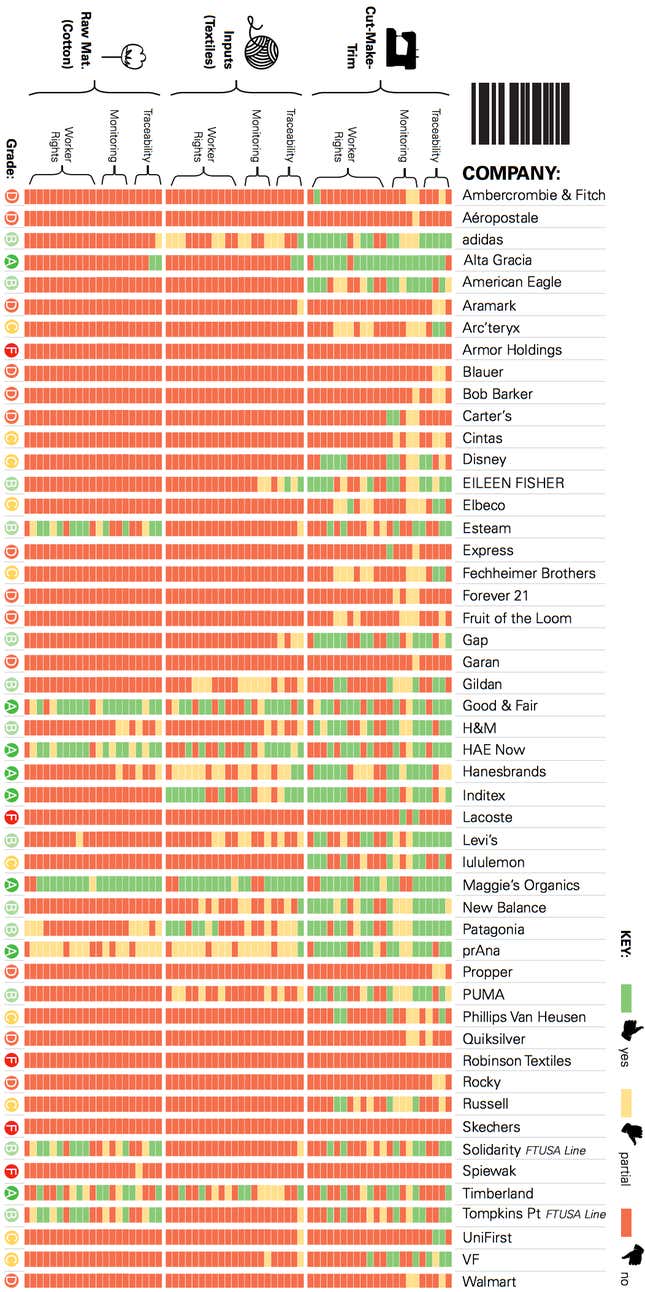

“All kinds of controls?” An in-depth study rating Wal-Mart’s supply chain practices and 49 other companies making apparel—out a week before the Nov. 24 fire—gave the company a failing grade on a variety of supplier-related practices that are standard procedures for some companies. Not For Sale, a non-profit that fights against human trafficking, analyzed how these companies guard against child and forced labor by ensuring workers can organize and bargain collectively to protect their rights, for example, and whether they used suppliers that paid reasonable wages, did any training and monitoring, or ensured decent working conditions. It also looked at how well companies traced their supply chains to make sure all subcontractors were known to the organizations—the area that got Wal-Mart into trouble.

Using the American grading system in which A, B or C are passing grades, Wal-Mart scored a D overall—failing on most fronts. An area that Wal-Mart said today is of particular concern relates to the transparency of sub-contractors, a responsibility the company says is up to its suppliers. “It is a must that they disclose factories they use for our production,” Kamalanathan told Reuters. “Once we know who these factories are, then we initiate the process for an audit to occur.”

But Wal-Mart did know the Tazreen factory where the fire struck. It inspected it itself in 2011, and found serious fire-safety concerns. Wal-Mart said the factory had been removed from a list of authorized factories and had no idea it was still part of its supply chain.

In reality, many companies that say they do audits don’t do them very well. According to the Not For Sale study, only 8% of the companies surveyed do unannounced audits or interview workers off-site in most cases.

Wal-Mart is hardly the only Western company that’s fallen short when it comes to monitoring and improving the conditions of the factories that make its products. Other well-known brands including Carter’s, Lacoste, Quiksilver, and Skechers also earned failing marks related to protecting workers’ rights, ensuring safe conditions, doing training, and keeping track of which companies produce products for them. What’s especially noticeable is that even the firms that are good at monitoring their immediate subcontractors (the “Cut-Make-Trim” level of the process) often have almost no idea what’s going on with their suppliers of textiles and raw materials. (See the full results here).

How well apparel manufacturers know their own suppliers