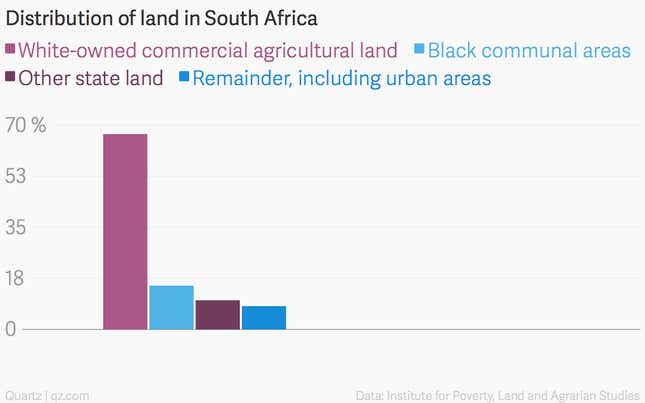

South Africa is retooling efforts to fix one of the main legacies of apartheid: the fact that in 1994 the white minority of less than 10% owned more than 90% of the country’s land. But the moves may tie less to tillage than to the travails of the ruling party.

President Jacob Zuma, who heads the African National Congress that led the transition to majority rule and still governs the country, sparked debate recently with a proposal to cap the amount of farmland that anyone can hold at 12,000 hectares (29,652 acres).

Zuma, who also proposes to bar foreigners from acquiring farmland, has cast the moves as a series of steps to right the imbalance left over from the era of minority rule. “We are taking these actions precisely because the fate of too many is in the hands of too few,” Zuma, who also aims to create one million jobs in agriculture by 2030, told parliament in February.

Though land reform has proved to be thorny for many countries on the continent that, like South Africa, struggled to achieve democracy, the latest proposals by Zuma suggest that the president may be playing to onlookers as much as attempting to address inequities, analysts say.

The push to pick up the pace of redistribution reflects a landscape in which the ANC has seen its majority shrink amid a slowdown in the economy.

Zuma is slated to take questions on Wednesday in parliament, where the Economic Freedom Fighters, an upstart party, won 25 seats last year on a platform that includes calls to expropriate and redistribute land without compensation. The Democratic Alliance, the main opposition group, proposes to allow people in urban areas who live in government housing for two years to take title to their homes, too.

Thus far, the program to redistribute land, which relies primarily on a combination of grants and loans that prospective farmers can use to buy land or shares in existing farms, has proved to be a slog. Despite a goal of reallocating 30% of the 82 million hectares owned by white farmers by last year, the government had managed as of 2011 to transfer about 6.2 million hectares, or about 7.5%, according to the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS).

Still, experts say the cap that Zuma put forth bears little relation to the distribution of arable land in South Africa, where only about 22% farmland has rainfall required for cultivation. ”A crude area measurement like 12,000 just shows how detached from reality this debate is,” Edward Lahiff, a lecturer at University College Cork who studies land reform in South Africa, tells Quartz. “If you’re talking about the value of land you might have a more realistic point.”

Though 45% of black South Africans – mostly those in rural areas – want access to land for food production, nearly half of them want one hectare or less, according to PLAAS.

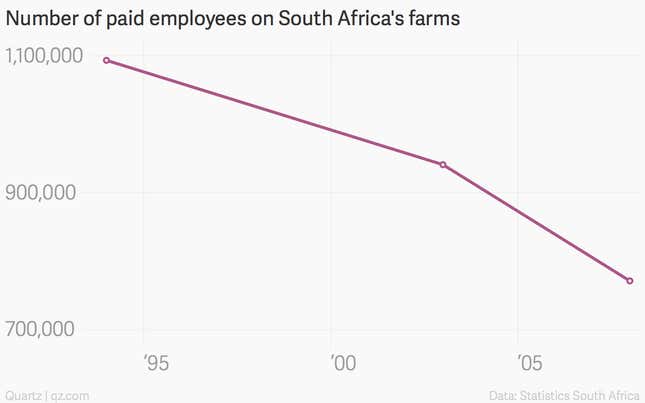

The effect of the proposals on the prospects of most South Africans also may be limited by the republic’s economy, which relies less on farming than on other sectors to fuel growth. Agriculture contributed 2.3% to South Africa’s gross domestic product of $328 billion (US) last year, mirroring a similar trend in post-industrial economies worldwide.

“If you compare land today with land 100 years ago, that same piece of land produces multiples of what land produced 100 years ago,” says Dawie Roodt, chief economist at the Efficient Group, a financial services firm based in Pretoria.

That’s not to suggest that land redress doesn’t matter. South Africa’s constitution aims to reverse the effects of earlier codes that reserved most of the republic’s land for whites. Nevertheless, adds Roodt, “What the president is proposing and what’s happening in the world are two different things.”