When the Obama administration changed the rules to make it harder for US companies to move their headquarters—and their taxable profits—overseas through the reverse mergers called tax inversions, it put the kibosh on at least one such deal. But now critics of the move say rules have made it easier for foreign companies to scoop up US firms. (paywall)

The logic is that US shareholders, no longer able to move their companies abroad to take advantage of lower tax rates, will be more likely to sell them outright to get a better value for their stock.

Republican senator Rob Portman cites foreign takeovers as evidence ”that one-off solutions instead of tax reform simply won’t work,” which is, ironically enough, exactly what the Treasury Secretary Jack Lew said when he announced the new measures.

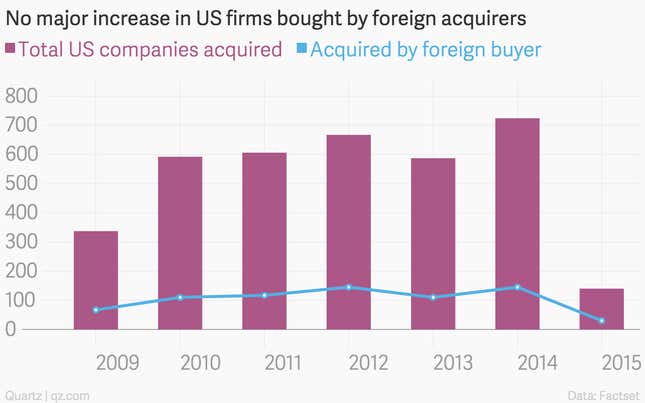

But lets get to the numbers—is there a noticeable increase in foreign deals since the rules changed? Not really. The share of US company acquisition deals worth more than $100 million that involved foreign buyers has averaged 19.96% since 2009; so far in 2015, 21.43% of announced US acquisitions are targeted by foreign buyers:

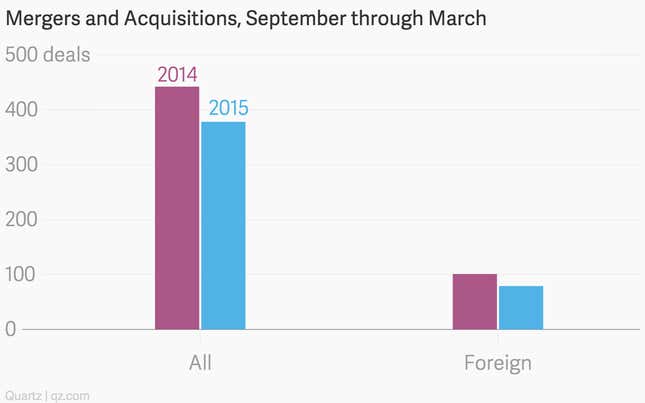

And let’s dig a little bit deeper into the numbers cited by critics, which compare deal-flow since the rules changed in September 2014 and compare it to the same period a year previous.

There have actually been fewer announced foreign acquisitions of US companies since the new rules were put in place…

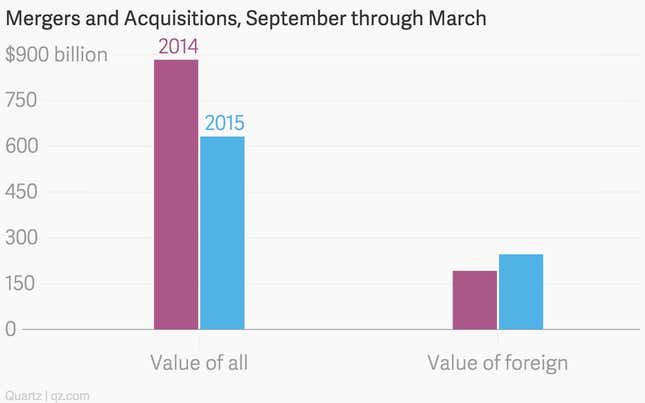

…but the foreign acquisitions have been of a slightly higher value:

That due mostly to the biggest of the new deals, the $65 billion sale of the US-based Allergan to Ireland’s Actavis. The deal only comes after the Canadian firm Valeant spent months trying to purchase the company well before the new rules were enacted. And Actavis is Irish in name only—it is an American firm that moved its “headquarters” to Ireland in a 2013 tax inversion; management remains in New Jersey. It’s also important to remember that, of the 79 foreign acquisitions of US companies announced this year, 48 are still pending and may fall through.

It doesn’t necessarily follow that rules blocking tax inversions would lead to more acquisitions by foreign firms. Since most companies seeking inversions tend to say—at least for public relations purposes—that tax considerations are just one part of the strategic logic of a merger, it seems unlikely that they would be the guiding factor in a firm’s sale.

And where tax considerations are the guiding factor in the sale—say, for pharmaceutical companies living off patent royalties—companies are already able to create many of those same benefits with offshore profit-shifting and stock buy-back efforts.

Of course, that only underscores the need for corporate tax reform. The ultimate motivation for tax inversions—as well as more prosaic tax avoidance by US companies—is the broken tax system that corporate lobbying is, so far, dedicated to preserving.

But beyond taxes, there is a much simpler reason for the growing value of US companies being bought by interests outside the country: The US is one of the few bright spots for growth in the global economy, and many international firms are seeking to expand their operations there as hedge against growth worries elsewhere.