A lot of people are trying to figure out what the future of music will look (sound?) like, and that now includes at least one heavy hitter on Wall Street.

A New York-based hedge fund, P Schoenfeld Asset Management, is trying to force French media conglomerate Vivendi to, among other things, spin off its Universal Music Group division, the world’s biggest record label and one of the biggest music publishers.

The hedge fund is preparing to formally challenge Vivendi at its annual meeting next month, the Financial Times (paywall) reported, and rally support among other shareholders for its desired course of action, which may also include demands for a higher dividend.

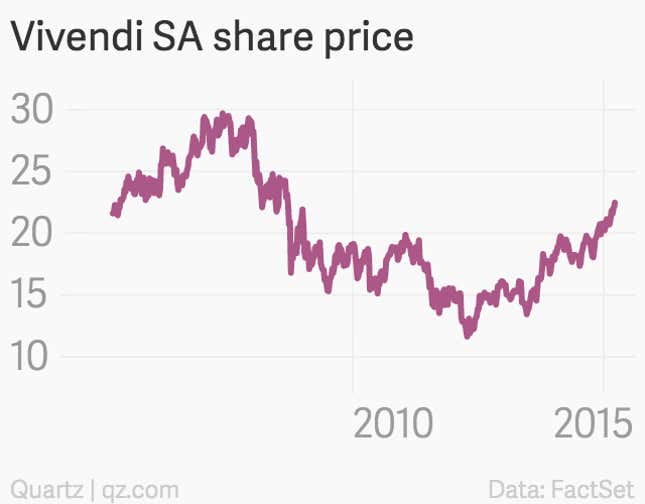

Vivendi’s share price is already trading at its highest level since 2009, but the hedge fund presumably thinks it could be higher. The fund did not respond to Quartz’s request to elaborate on its strategy by the time of publishing.

Vivendi CEO Arnaud de Puyfontaine has already said that music is central to his strategy at the company, declaring he would only sell Universal ”over my dead body.” But it’s still worth analyzing why some investors want to see that happen.

In one sense, the outlook for recorded music seems pretty bleak.

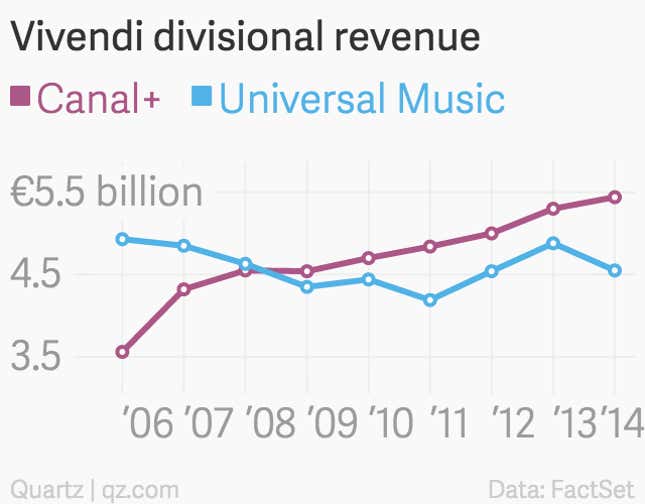

Revenue at Universal has declined over the past decade, a period during which consumers have defected from buying CD albums in full, to purchasing and downloading individual tracks through services like iTunes. And most recently, there has been an uptick in subscriptions to services like Spotify.

But some analysts think that the rise of streaming could eventually make music much more valuable. “We believe the value of music content will grow strongly over the next 10 years, driven by increased consumption of music via paid streaming platforms, including Spotify, Deezer and Beats Music,” Credit Suisse said in a note last year.

The investment bank has forecast that global recorded music revenue could even return to growth next year. At the moment streaming is a niche activity. Only 7.7 million people have taken out streaming music subscription in the US, according to figures from the Recording Industry Association of America. Compare that to streaming video (By comparison, Netflix had 37.7 million subscribers in the US at the end of last year.)

Yet streaming music could go mainstream, particularly if Apple can convince some of the 800 million credit card holders it already has on file to pay for its offering.

For its part, Universal has been leading a behind-the-scenes campaign to get consumers to pay more for music. It has pressured Spotify to drop its free, ad-based tier of subscriptions, and probably influenced Apple’s widely expected decision to not offer a free option when it launches its streaming service in the coming months.

A report in the New York Post earlier this month suggested billionaire John Malone was interested in buying Universal. But if more bullish forecasts for music are right, now might not be the best time for Vivendi to sell the world’s biggest record label.