Why China’s economy is slowing and what it means for everything

It’s really happening.

It’s really happening.

China, an increasingly important engine of global economic growth, is slowing fast.

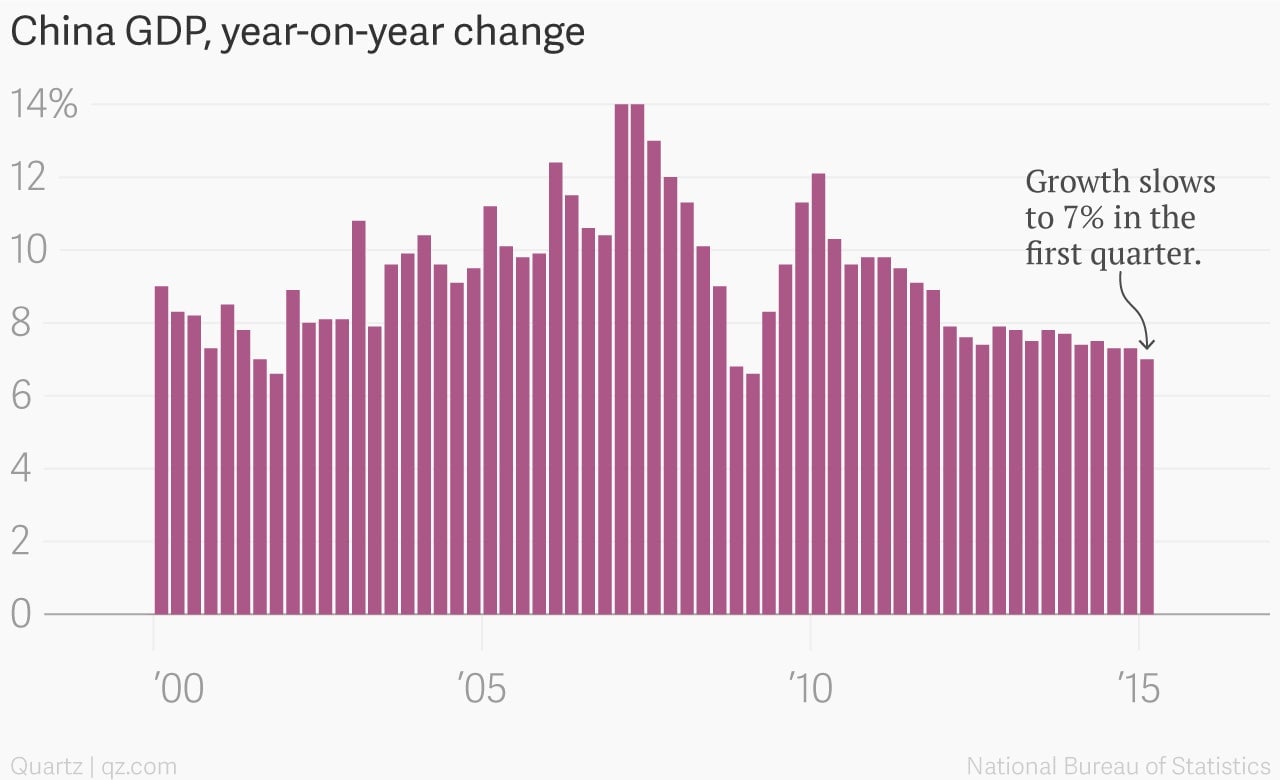

Just last week, China’s National Bureau of Statistics reported that growth in the world’s second-largest economy had slowed to 7%, the slowest clip in six years.

Skeptics would note the remarkable coincidence that growth arrived exactly on the government’s 7% growth target during the quarter. But that’s sort of missing the point. The government itself is admitting that its growth targets look increasingly difficult to hit over the coming year. During the week, Premier Li Keqiang was quoted by state media as saying the first-quarter data are “not pretty.”

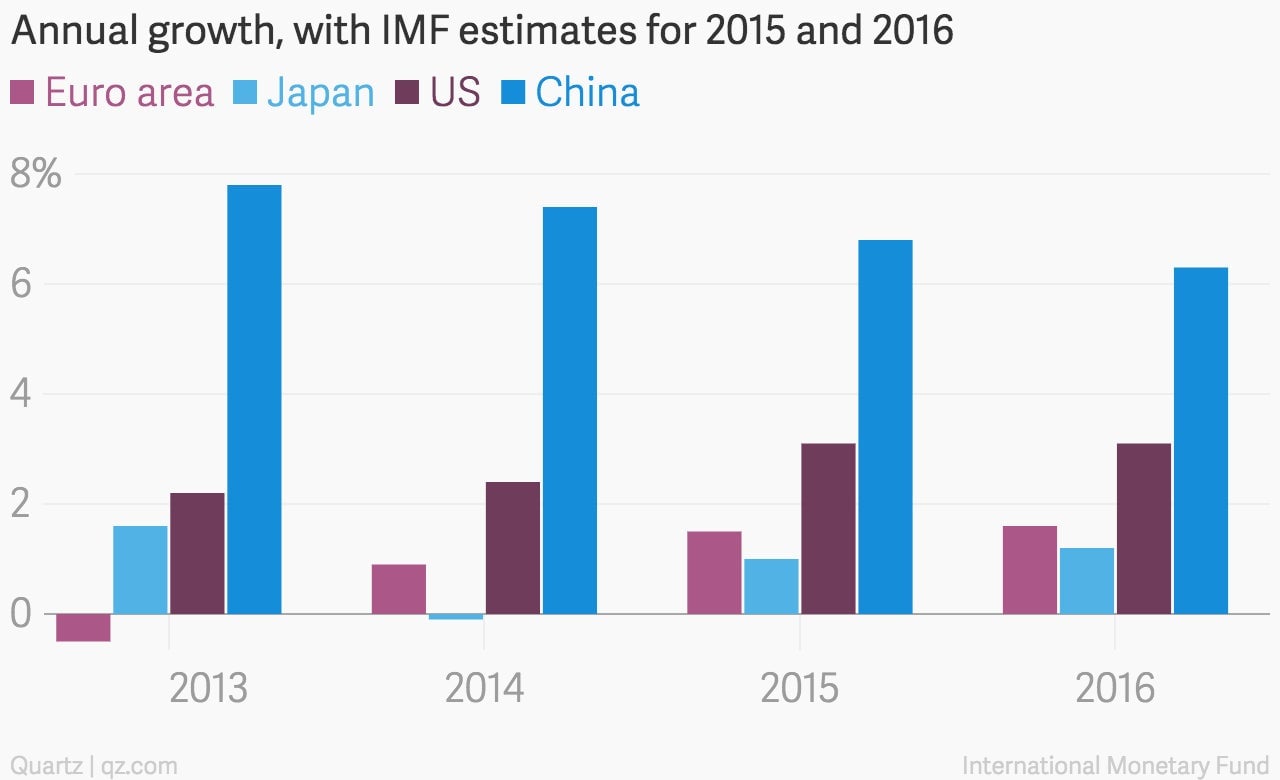

At any rate, in its annual World Economic Outlook (pdf), the International Monetary Fund projected that Chinese growth would fall to 6.8% in 2015, and 6.3% in 2016.

A big deal, but not too big

This is both a big deal, and kind of not a big deal. For one thing, growth rates of more than 6% are nothing to sneeze at.

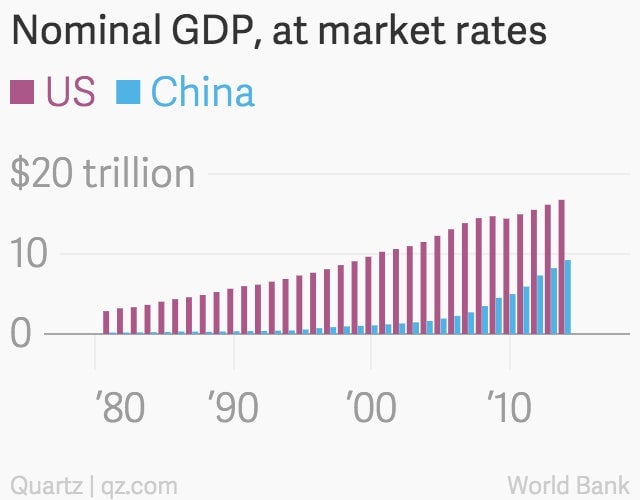

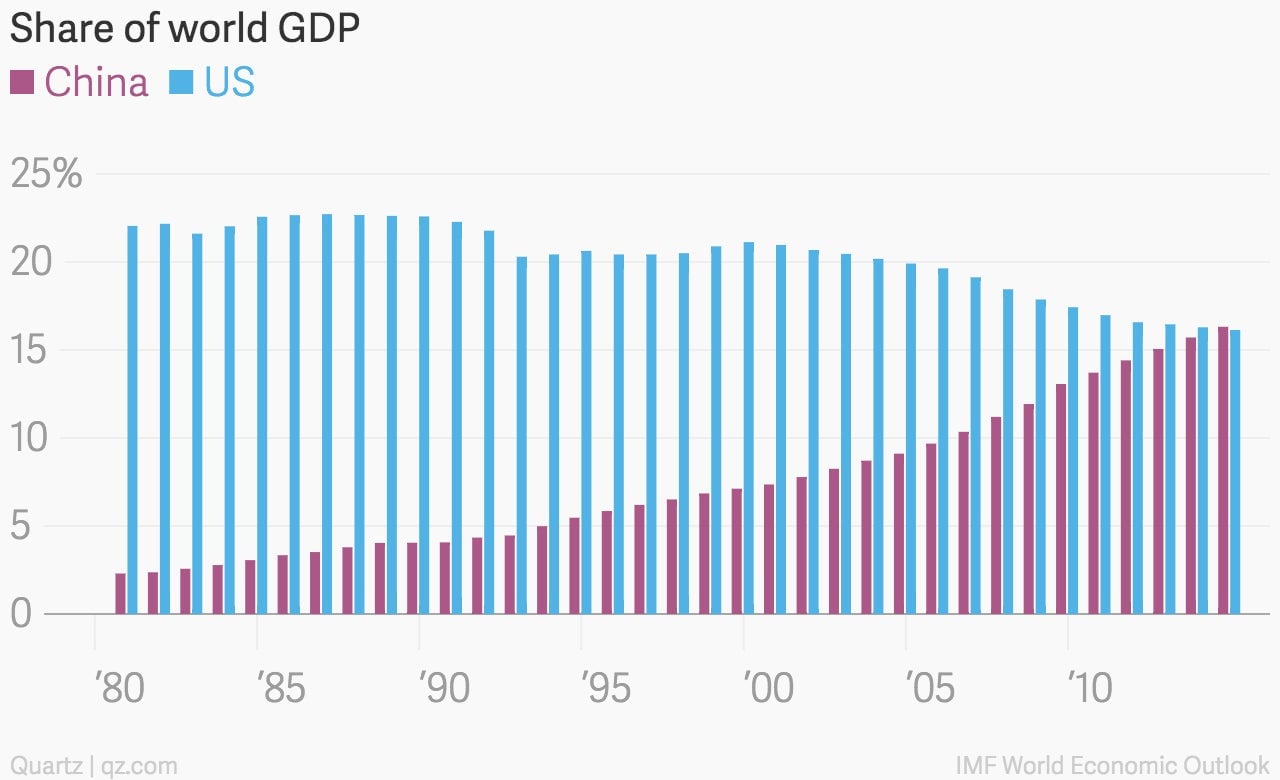

At its fastest, the US economy only managed to reach a 5% growth rate during one quarter over the last decade. And another thing, it’s not as if China is going away any time soon. In fact, by some measures China’s economy is essentially the same size as that of US. (By other measures, such as the small chart above, it’s a bit more than half the size of the US’s nearly $17 trillion economy.)

But by both measures, China is at least the second largest economy in the world. Does the fact that it’s losing steam mean we’re doomed to another global slump? Well, no. Thankfully, developed market economies such as the US seem to be in decent shape and set to pick up a bit of slack. The world economy grew by 3.4% in 2014, according to the IMF. And it’s projected to expand by 3.5% and 3.8% in 2015 and 2016.

Projections are just guesses, really

But let’s be honest. Economists tend to be pretty terrible about predicting major shocks to the global economy. If something were to go horribly wrong with the Chinese economy it would be a big deal with the global economy. Nobody expects that. But nobody expected that the US economy and financial system would implode in 2008.

And the fact remains that China is trying to do something pretty difficult. If the economy of the People’s Republic is a freight train, Chinese economic policymakers are trying to pull off a large scale overhaul of the engine while the locomotive barrels down the tracks. In fact, they’ve been working on the engine for a while.

While many in the West still think of China as primarily an industrial, exporting hegemon, in fact industrial growth (right) has been cooling fast in recent years. In March, growth in industrial production fell to 6.4%, the lowest since the Great Recession.

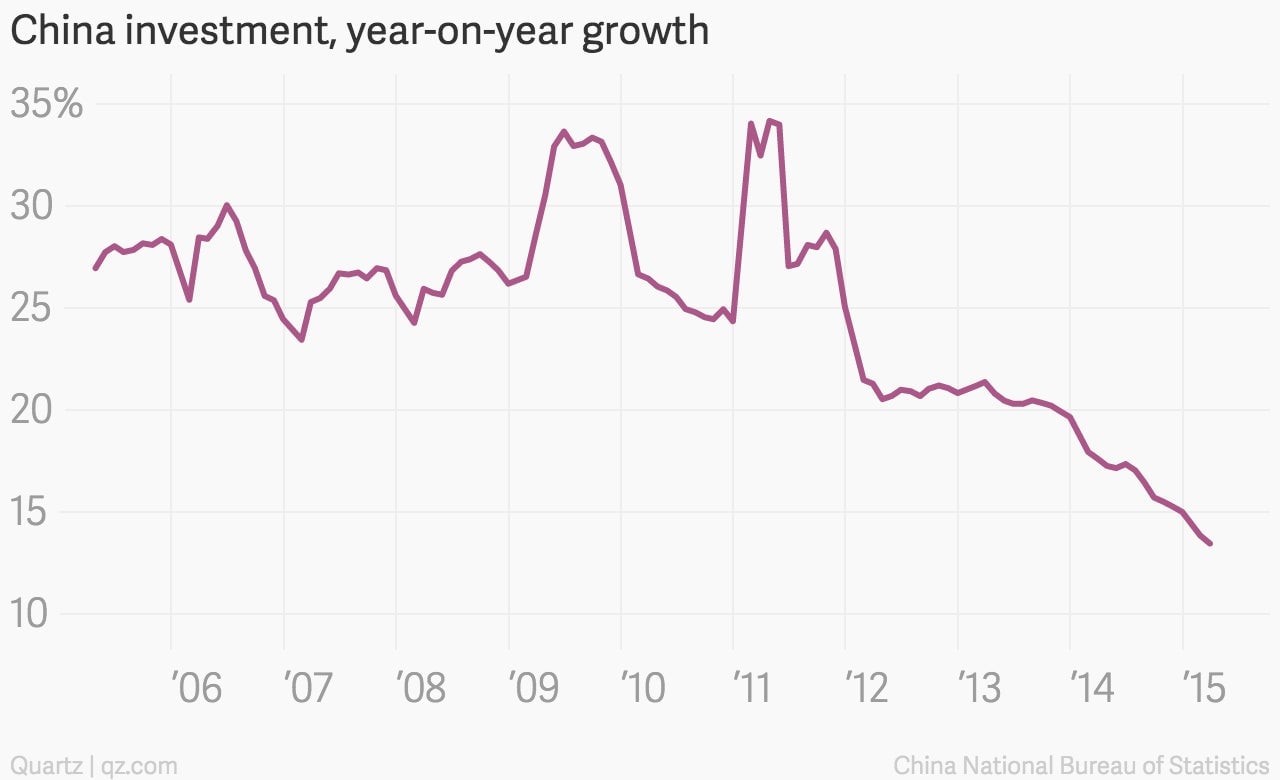

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, when some of China’s most important export markets, such as the US were mired in the deepest recession since the Great Depression, China embarked on a massive investment binge. But that, too, is now slowing. Investment growth declined to 13.5% in the first quarter, the slowest in since 2000.

In an ideal world, Chinese consumers would pick up some of the slack. But retail sales growth also continues to slump, it fell to 10.2% in March, worse than expected. In other words, its unclear what will fuel China’s economic engine.

Capital outflow

So, it’s far from clear that China will be able to easily pull off such a transition. And there are indications that the foreign investors that have pumped billions into the Chinese economy in recent years aren’t waiting around to find out.

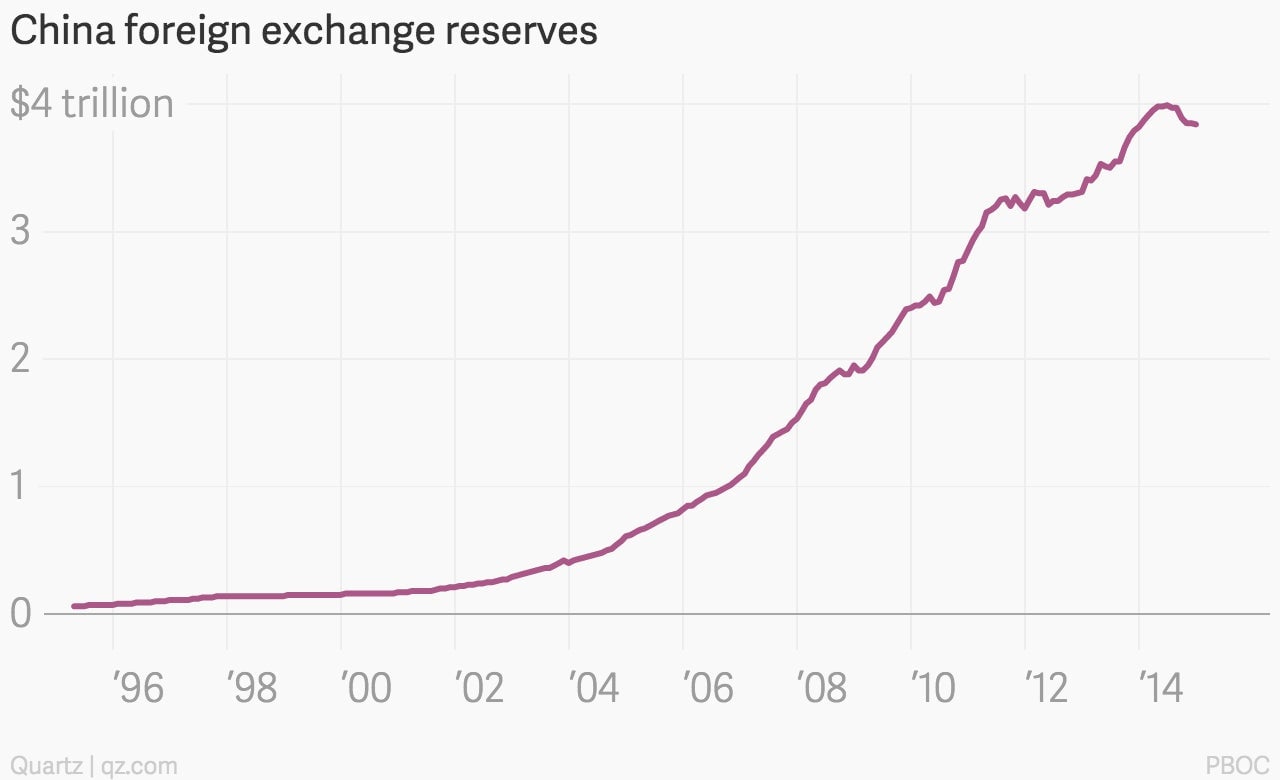

How do we know? Well, we can look at Chinese foreign exchange reserves. As part of its policy of keeping its currency cheap to boost exports, China has amassed nearly $4 trillion dollars in reserves in recent years.

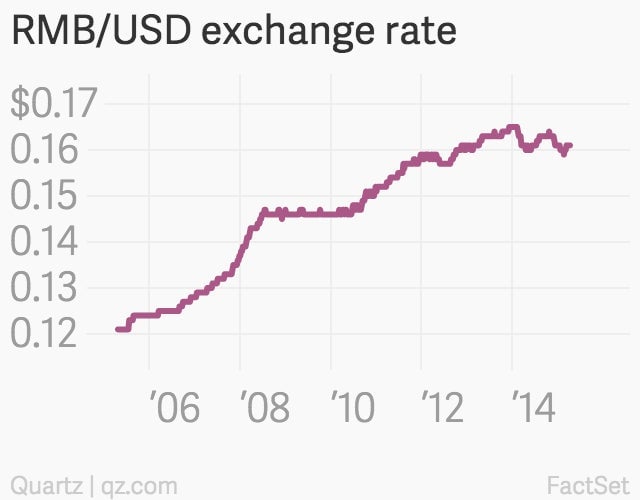

Here’s how it worked. Essentially, when China’s currency, the yuan or RMB, would strengthen against the dollar, the government printed fresh yuan and used them to buy dollars. That increased the supply of Chinese currency floating around in the market, and shrunk the supply of dollars—because the Chinese government bought them and pulled them out of circulation. Increased yuan supply and smaller dollar supply weakened the Chinese currency.

But it recent months, the opposite seems to be happening. The governments pile of dollars is shrinking a bit, suggesting it has been selling dollars to try to keep the yuan from weakening too much. The yuan isn’t strengthening the way it has been in recent years, which suggests investors aren’t as eager to invest in the country.

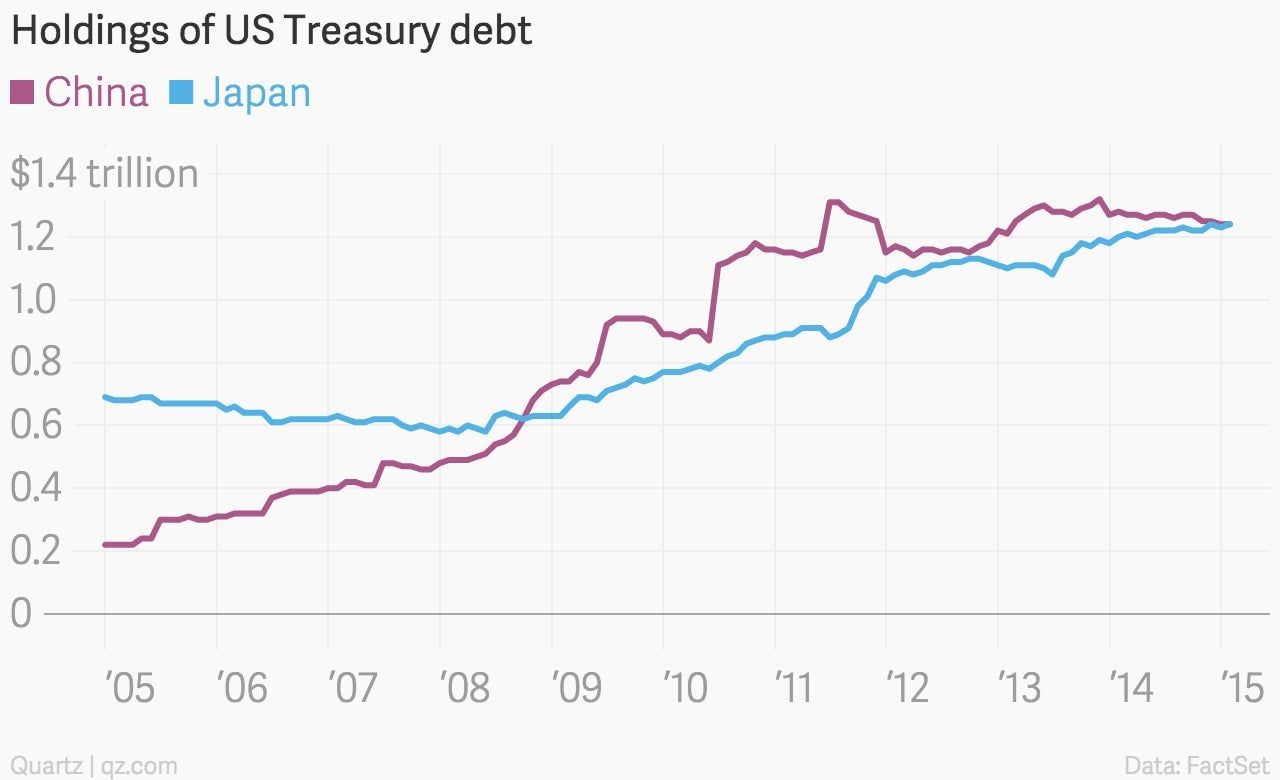

And since China’s pile of dollars has stopped growing, the country hasn’t needed to buy as many US government bonds. (Treasuries are traditionally a key place where China would stash its cash.) Lo and behold, China this week lost the crown of the largest foreign creditor to the US, as Japan overtook it.

Trade winds

So, China’s slowdown doesn’t doom the world to recession. But its path forward is far from clear. And investors seem to be a bit jittery. The biggest economic impact tied to the China slowdown could well be outside of China, particularly among the suppliers of the raw materials China has used to fuel its industrial and investment binge in recent years.

For example, China consumes roughly 47% of the world’s base metals, up from 13% in 2000, according to the IMF. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that metal prices are now roughly 44% below their 2011 peak.

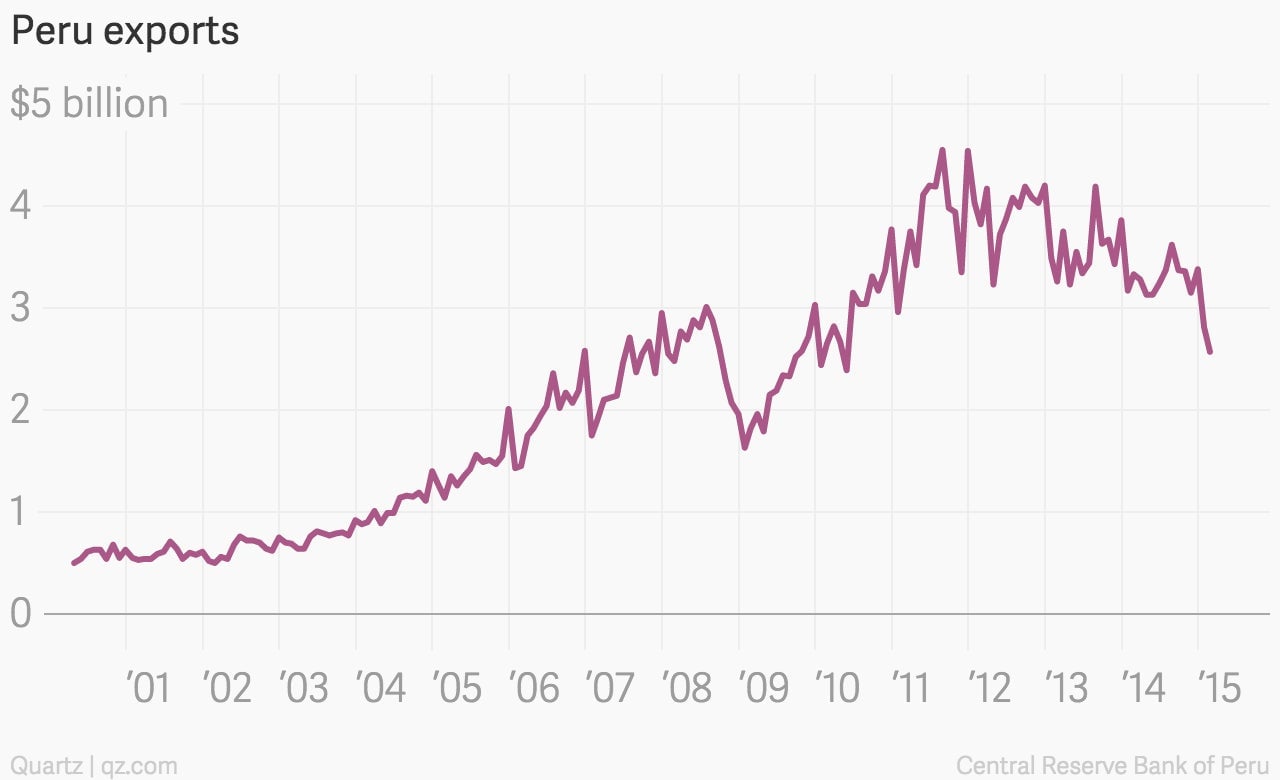

China’s slowdown has weighed on copper prices, for instance. And that’s weighed on copper exporters, such as Peru.

Likewise, iron ore prices have hammered Australia’s revenue from exports of the raw material to Chinese steel mills.

The fact that Brazil is being battered by a similar trend only adds to the dour outlook for the South American giant. The IMF projects the Brazilian economy will fall into recession in 2015 and contract by about 1%.

What is to be done?

That’s the trillion-dollar question. Will China be able to pull off a transition to a different economic model without a hiccup? Probably not. That doesn’t mean the economic miracle in the People’s Republic is over. But it does open the door for a bit of volatility over the next few years. Can the government pull it off?

The verdict of the Chinese stock markets is a resounding yes. Bourses in both the mainland and in Hong Kong have soared in recent months, even amid a deluge of weak economic data. That suggests that investors there are expecting the government to launch another big stimulus push in order to jack-up growth. We’ll have to wait and see.