We often like to think about African politics and its governments as being dominated by one ethnic group. The exclusion of some groups then translates into ethnic tensions as groups attempt to wrestle power from one another. For many of us, this narrative seems to make sense. We use it to explain the root cause for the civil wars, revolutions and coups d’état we’ve seen over the last five decades.

But a new paper (ungated version available here or here) published in Econometrica by economists Patrick Francois, Franceso Trebbi and Illia Rainer argues that we might have the story backwards: Ruling coalitions in Africa are actually ethnically inclusive. And they are inclusive because leaders want to reduce the probability of revolutions and coups occurring against them. The authors conducted their analysis using a dataset that they painstakingly compiled on the ethnic composition of cabinet ministers in 15 African countries over the period 1960 to 2004. They choose to focus on cabinet because in most African countries power ultimately resides with the executive branch of government. Here are some interesting findings from the paper:

Ruling coalitions are large, often covering 80% of the population

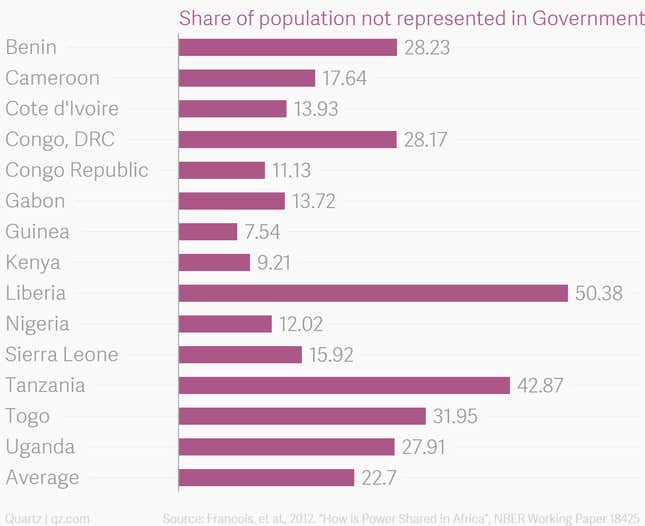

The chart below taken from the working paper version of the study shows the average share of the population not represented in cabinet in each of the 15 countries from 1960 to 2004. This ranges from as little as 8% of the population excluded from representation in cabinet in Guinea to about 50% in Liberia. The average for the 15 countries is 23% implying that, on an average, an impressive 80% of the population finds representation in cabinet.

Another way of looking at the degree of ethnic representation is to see whether an ethnic group’s share in the total population matches its share in cabinet. An ethnic group making up, say, 20% of the population would be perfectly represented if its share of cabinet seats was exactly equal to 20%. This is precisely what the authors find for the 15 countries studied: population ethnic shares very closely mirror cabinet ethnic shares. And this pattern of ethnic representation also holds for the top cabinet posts of Finance, Defence, Justice, Home Affairs, Foreign Affairs and so on.

Little ethnic advantage accrues to the head of state

We often think that African heads of state disproportionately favour their own ethnic group in the allocation of cabinet posts. Messrs Francois, Trebbi and Rainer find that this ethnic advantage (or “ethnic premium” as they choose to call it) is actually very small. They estimate that heads of state are only able to set aside an additional 2 cabinet posts (for an average 25 member cabinet) to their own ethnic group over and above their group’s share in the population. This leadership advantage is not different in magnitude to that enjoyed by formateurs in western parliamentary democracies.

The rule of the minority in Liberia and the role of the US

Liberia is the only country studied by the authors that shows a great degree of ethnic exclusiveness. Only 50% of the country’s population found representation in cabinet over the period 1960 to 2004. The authors, however, find that most of this ethnic exclusiveness was limited to the period before 1980 when Liberia was ruled by Americo-Liberians, a very small minority of freed American slaves. Americo-Liberians, who make up 4% of the population, were able to set aside about 50% of cabinet posts for themselves. And their minority rule was largely buttressed by outside help most of it from the US. The rule of the Americo-Liberians collapsed once American help waned.

Why do African heads of state choose to share power in this way?

The authors argue that it’s largely due to the fear of coups and revolutions. By inviting elites from the country’s different ethnic groups to join government, heads of state are hoping that non-elites (the “masses”) will not see the need to force a change since their “sons” and “daughters” are ministers in the government.

If ruling coalitions are so inclusive then why is ethnicity such a salient feature in African politics? For instance, the 2008 post-election violence in Kenya was largely seen as having been ethnically motivated in spite of Kenya’s government being ethnically inclusive (as demonstrated by the authors of the study). A possible reason was advanced by David Posner in his book Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Africa. According to Posner, some elites might encourage the perception that their own ethnic group is grossly underrepresented in government as a strategy to win elections or inspire a coup. In this way, ethnicity still finds its way to the centre of politics.