In September 2002, McDonald’s was hurting. Same-store sales in the US were down, its stock was sinking, and critiques of its business, including Eric Schlosser’s 2001 exposé, Fast Food Nation, had sullied its once shiny brand.

“The challenges facing McDonald’s come supersized,” TIME wrote in September of that year in a story headlined, Can McDonald’s Shape Up? “Its home market is all but saturated, its sterling reputation for fast, friendly service and cleanliness is tarnished, and customers are putting a growing premium on freshness and taste, neither of which McDonald’s is renowned for.”

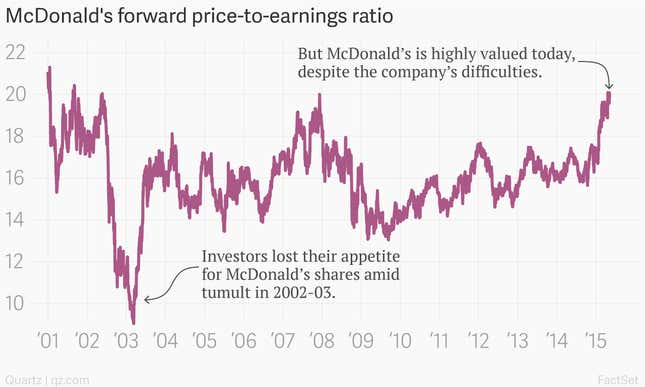

Though the company was trying to appeal to those tastes—offering up new products like a Grilled Chicken Flatbread sandwich and launching its upscale in-store coffee shop, McCafe—the effort didn’t appear to be working. Sales continued to sink, as did the stock price. By March 2003, the shares were down 70% from their November 1999 peak. In what Bloomberg termed, “McDonald’s Hamburger Hell,” the company suffered from complaints of bad customer service, a floundering CEO, and disgruntled franchisees.

If this story sounds familiar, that’s because it’s happening all over again. Sales in the US have been down six quarters in a row, dropping 7% in 2014. The fast-casual competition has shifted from Cosi and Subway to Chipotle and Shake Shack. New offerings like the Artisan Grilled Chicken sandwich and Build-Your-Own-Burger kiosks are not sufficiently boosting revenues, franchisees are complaining about high costs, service remains slow, and former CEO Don Thompson has been replaced by a Brit, Steve Easterbrook.

But if history is any indicator, there is hope yet for the Golden Arches. During its last crisis, the tide had started to turn by October 2004. The Economist marveled over the chain’s “remarkable turnaround,” which included the introduction of healthier options like salads that had a “halo effect.” New technologies and attention to improving existing stores (rather than opening new ones) remedied bad service.

As a result, sales, profits, and the company’s share price climbed. Between March 2003 and October 2004, the stock rose 105%, outpacing the 35% gain in the S&P 500 over the same period.

When McDonald’s announced its latest Turnaround Plan last Monday, the response was skeptical at best, with many noting that its numerous restaurant closures might not be sufficient without changes to the menu, which weren’t the focus of the announcement. The share price fell upon the announcement.

And yet, restaurant closures are just one part of what appears to be a turnaround strategy modeled on its reforms from the early 2000s. Separately announced menu changes that address new customer preferences—like antibiotic-free chicken and even kale—will likely offer the “halo effect” its salads once provided. And new technologies like Apple Pay and its own app announced in March could revive customer service.

It’s worth noting that McDonald’s still has the highest sales of any restaurant chain in the US, its largest market—over $35 billion in 2014, nearly three times that of Subway and four times that of Burger King. And investors haven’t given up on McDonald’s. The company’s price-to-earnings ratio—a measure of its expected future earnings growth—is lower than those of competitors like Chipotle and Yum! Brands. But it’s still higher than it was during the company’s last comeback in 2004.