Richard Thaler spent most of his career as an academic outsider. And along the way, he became one of the founding fathers of a once-obscure blend of psychology and economics that we now know as behavioral economics.

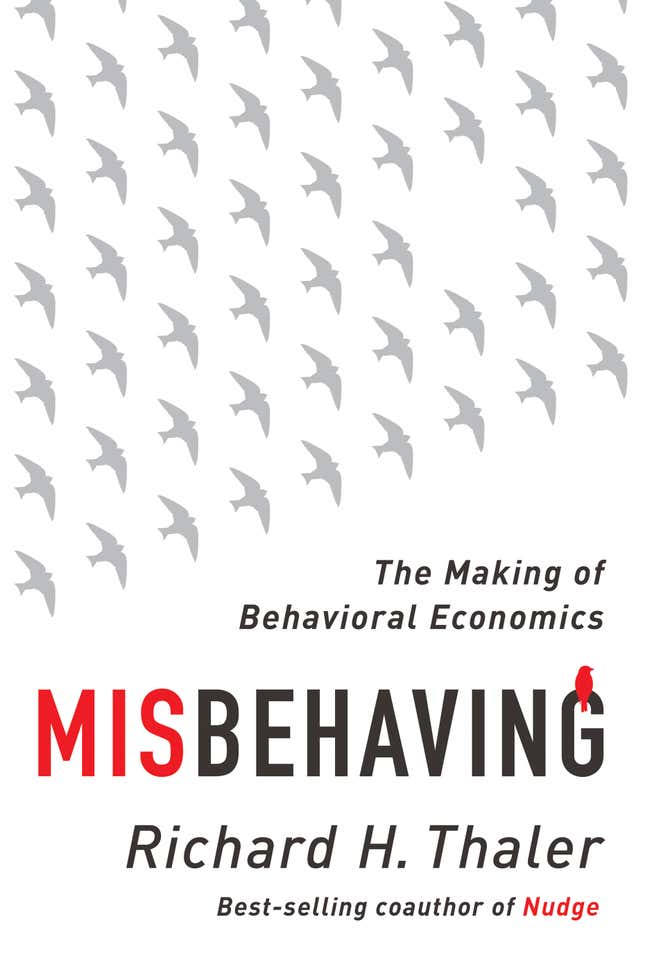

An economics professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, Thaler is now president of the American Economic Association. Just how he went from the fringes to the very heart of the profession is the story told in his latest book, an economics memoir titled Misbehaving.

Misbehaving is, in a way, the backstory to the book Thaler is best known for, the 2008 best-seller Nudge with legal scholar Cass Sunstein (to whom Quartz also talked recently.) Nudge argued that by harnessing the power of behavioral economics, policy makers, business people and other “choice architects” can steer people toward decisions that maximize their well-being.

In Misbehaving, Thaler details how he laid the basis for behavioral economics with his career-long effort to confront the fundamental flaw with formal economic models built upon “rational expectations,” which dominated the profession for the last half century.

Compared to the economic actors portrayed in formal models—creatures Thaler calls Econs—people misbehave. They get overconfident. They don’t ignore sunk costs, but act as if it were still possible to claw those back. They lack willpower. They struggle with self-control.

Over lunch at a restaurant in New York, Thaler—he ordered the lobster roll—offered his thoughts on how economics edited human behavior out of its equations, and whether the behavioralists have finally won the war to put them back in. The interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Quartz: The book is great. It’s a really readable, warm account. And it’s got a lot of people in it, which kind of makes sense because your work focuses on people. Is that why you wanted to do it as a memoir?

Thaler: I did it as a memoir because I couldn’t figure out any other way to do it. In fact, it’s not the book I sold.

Explain that.

The book I sold was called Snags.

And what was that supposed to be?

It was supposed to be the stuff we trip on. I almost thought of it as a prequel to Nudge… I worked on Snags for, like, a year and a half. Not full time, because I have about four other jobs other than writing books. So I just said, “Let me start writing stuff that I find amusing or interesting.” So, I wrote a bunch of these and I showed them to [best-selling business author] Michael Lewis who is a buddy of mine. (A good writing coach.) And he was very encouraging, and he said, “Yeah you, got to do it this way.” And I said, “OK.”

It’s a real approachable way to write. And you pick up a ton of economics along the way.

No one has ever been able to name a book that is a funny, substantive, intellectual memoir. It seems to me the null set. [Physicist Richard] Feynman’s book Surely You’re Joking, Mr Feynman! is funny and a memoir. But there’s no physics. It’s just about lock-picking and bongo-playing… My editor said, “Don’t call it a memoir. Whatever you do, don’t call it a memoir.”

Why?

Because no one will buy it. I mean, nobody wants to read the memoir of some guy they’ve never heard of, who is working in a field they’ve never heard of. Well, some people have heard of the field now.

The title refers to people who are sort-of misbehaving. Or rather, people behaving like people rather than what you call Econs.

They’re only misbehaving if you use [the] economists’ definition of good behavior. So like leaving a tip, at this restaurant that we will never return to, is misbehaving. Most people would think of it as good behavior.

So how did economics manage to take humans out of economics? I mean if you’re studying economics, which is how humans buy, sell and trade, it seems like a bad idea not to somehow take human behavior into account.

Economics was pretty behavioral right up through [John Maynard] Keynes, with his brilliant “beauty contest” and “animal spirits.” [Editor’s note: The “beauty contest” was Keynes’ observation that stock-market investors would price shares based not on what they thought they were worth, "Leaving a tip at this restaurant that we will never return to is misbehaving [in economic terms]. Most people would think of it as good behavior." but on what they thought other people would think they were worth. “Animal spirits” was the phrase Keynes used for the fear and greed that sometimes overwhelm financial markets that are supposed to behave rationally.]

So, that’s 1936. That was kind of the end of people in economics. And it wasn’t intentional that that happened. The people like Paul Samuelson who started the mathematical revolution in economics didn’t mean to leave people out. But the easiest models to write down are models of rational choice.

You have that section of the book, where you’re describing these conventional models of economics to a room full of psychologists. And they’re laughing at the way economists think about the world, as if it’s a joke.

Exactly. And if you criticize it, they suspect, and rightly so in my case, that’s it’s because you’re not as good at math as them. You know, most economists are failed mathematicians or physicists. We have lots of MIT and Caltech undergrads that are now famous economists. And everybody who is an economist was really good at math in high school. And took AP [advanced placement] calculus. So you start taking more math courses in college and then you realize, shit, there are guys way better than me. So, you know you sort of slip into something that’s mathy, like economics.

You’re now head of the American Economic Association. Does that mean that behavioral economics isn’t controversial anymore? Did you win?

No. I mean, I certainly went out of my way to not write this book as “mission accomplished.” We ought to learn some lessons from Dubya. So behavioral economics now is not controversial for most economists under 40. That’s where I think we are. It’s still not the thing that is taught in ECON 101. I mean, that will take another 10 years.

What did you think of Piketty’s book?

Too thick. I’m one of the majority of people who have just read the reviews.

But a large part of the scientific contribution of that book is the collecting of the data. And then there’s the interpretation. And you know, no one really denies the fact that inequality is growing. Those numbers are indisputable. Now you can argue about whether that’s a bad thing. And you can argue about what caused it. And whether r > g is a good explanation for that. So lots of people who agree about the facts disagree about the interpretation.

Is economics about establishing the facts?

You know, it should start with that. In the end of the book I have this somewhat snide call for empirically based economics, evidence-based economics. One could reasonably ask, “What other kind of economics could there be?”