Remember the kerfuffle in the US about the “fiscal cliff” in 2013, or the regular showdowns since then about the government’s debt ceiling? How about Germany’s insistence on budget surpluses and no new borrowing, enshrined by the passage of a restrictive “debt brake” law (pdf), despite historically low borrowing costs?

In Britain, chancellor George Osborne wants to get in on the action, proposing a law that would oblige the government—and all in the future—to run a budget surplus. Since its unexpectedly large victory in last month’s election, Osborne’s Conservatives have doubled down on fiscal prudence as a key plank of their policy.

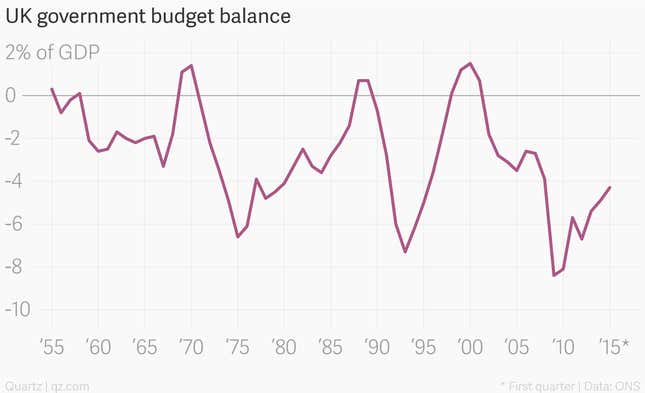

Forcing governments, by law, to spend only as much as they can raise in revenue would indeed be a rather radical break from tradition:

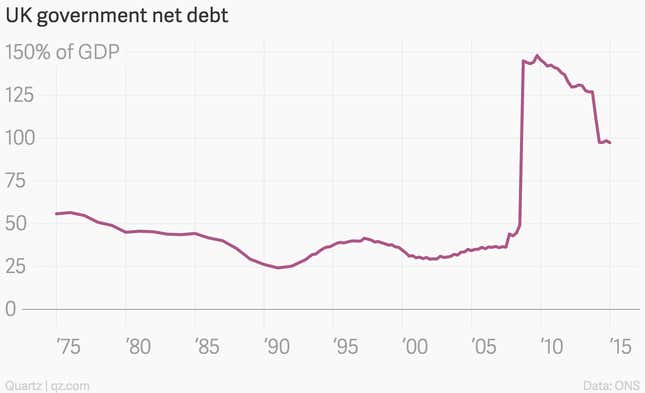

And look at how government debt has ballooned since the global financial crisis forced Britain into massive bank bailouts and saddled it with weak growth:

But there’s an important escape clause: the proposed budget-surplus law will apply only during “normal” times. Similarly squishy terms make other countries’ balanced-budget rules (pdf) equally flexible.

The economic wisdom of effectively outlawing deficits has prominent critics. Former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker published a report this week questioning such practices at US state governments, which “make budget trade-offs indecipherable, lead to poorly informed policymaking, pass current government costs onto future generations, and limit future spending options.”

The IMF released a note earlier this month (pdf) that concluded “while debt may be bad for growth, it does not follow that it should be paid down as quickly as possible.” When countries have “ample” fiscal room to maneuver, an admittedly-subjective concept, the IMF says there is a case for ”simply living with the debt.” In these cases, it’s better to let faster economic growth improve government finances rather than impose tax hikes, spending cuts, or other growth-sapping actions to reduce deficits and pay down debt.

The UK runs one of the largest budget deficits in the EU and also a higher debt-to-GDP burden than many of its neighbors. How much space does it have to let debt accumulate and deficits persist? Quite a lot, it turns out.

Britain’s debt-to-GDP ratio could double before the country would need to take “unprecedented steps” to avoid a spiral into default, according to Moody’s. The agency considers Britain’s “fiscal space” to be in “safe” territory, although not as safe as the US’s or Germany’s.

This is also reflected in the bond markets, where the UK government can borrow for 10 years at just over 2%—a shade less than the America’s 2.5%. This is hardly a sign of investor unease with a profligate, debt-riddled administration. The same applies, even more so, to Germany, where 10-year borrowing costs are currently around 1%.

So why do it? Osborne’s gambit puts the vanquished Labour Party in an awkward spot as it chooses a new leader, with the party’s economic acumen called into question after its stinging election defeat. The proposal is also a shrewd political gambit designed to appeal to voters.

After all, who doesn’t think it’s a good idea to live within one’s means?