For decades, the Philippines has been thought of as a sunny place for shady politicians, and an economic basket case.

The airport in the capital, Manila, has a comfortable waiting room reserved for citizens who work abroad—often as domestic helpers around Asia and the Middle East—signifying just how important remittances of their modest wages back home are to the country’s coffers.

And who can forget the political plundering? The nation has recovered some $5 billion embezzled by former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, but $10 billion remains missing. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, the Filipino president between 2001-2010, is herself battling charges of alleged plundering of state funds.

But the nation could be—whisper it—turning a corner. Arroyo’s popular replacement, Beningno “Noynoy” Aquino, rode to power on a ticket of fighting corruption and tax evasion. And while Asian leaders tend to quickly forget such promises, the smart money believes Noynoy means what he says.

“I think he may actually be honest,” the Asia Pacific head of a global accounting firm says of Aquino in somewhat startled tones (and requesting anonymity because he is not permitted to talk publicly about politics.) A hedge fund manager whose fund is bankrolling luxury real estate developments in Manila adds: “Aquino seems to be in it for the country, and not to enrich himself.” Filipinos feel the change too. Mary, 38, a Filipino domestic helper working in Hong Kong told me during a conversation in the city last month, with a cautious smile: “Noynoy may be the president who helps the people. We have waited so long for one who will.”

The country’s stock market is booming too, as this chart shows.

Because corruption has been endemic for so long, the Philippines has major growth potential just from government starting to do what it is supposed to. In 2010, the Economist noted, the Manila administration collected just one-fifth of the value added taxes it was owed. So the nation only spent 3% of GDP on education that year, and 0.6% on health.

But in the third quarter of last year, the Filipino economy grew a healthy 7.1%, beating expectations and spurred by government spending on infrastructure projects after the Aquino administration improved tax collection. The government is also prosecuting more tax evasion cases.

“Many see the [Philippines] entering a new era of economic prosperity and equitable development,” the Asian Development Bank said in a report (pdf p.1) last year.

In short, the Philippines is growing almost as fast as China, but is much less developed, so potentially has more gains ahead. It does not have China’s problems with wasteful state investment, which suggests China is running out of real growth and has caused a boom in subprime financing. The Philippines also has a healthy consumer economy. While household consumption was just 34% of GDP in China in 2011, the Filipino figure is much higher, at 74%, according to World Bank data.

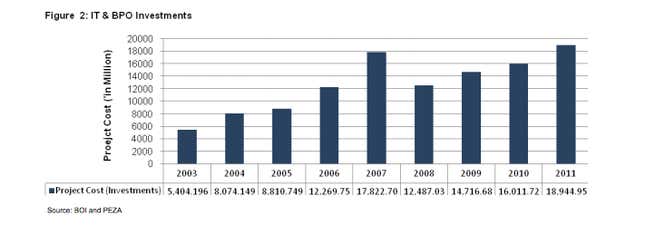

The good mood is encouraging banks and companies to expand their outsourcing businesses in the Philippines, attracted by the country’s young and highly literate population. The country’s board of investments forecasts the outsourcing industry will post (pdf, p. 2) 20% revenue growth for 2012. Here’s a chart of how that industry has grown so far.

As often happens when emerging markets turn a corner, Manila is in the throes of a real estate boom. The skyline is jammed with cranes, and some fear this is a bubble that is set to burst.

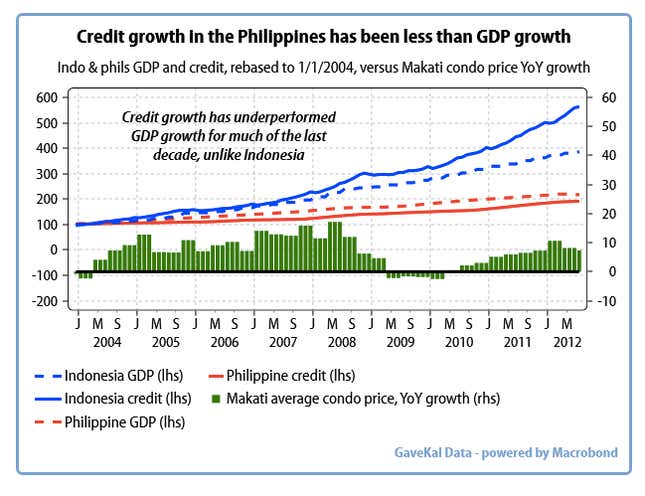

Research from Gavekal indicates the real estate boom can run for a while before pain sets in. The urban middle class is growing, with their household incomes expanding at around 6% a year, the research house says in a note. Gavekal also points out that mortgage rates have halved over the last five years, encouraging more young families to get on the property ladder. At the same time, credit growth has been relatively muted, at below GDP. That contrasts with neighbouring Indonesia.

Prices of luxury condominiums in Manila’s luxury enclave, Makati, are ticking up nicely but not soaring. And Manila remains a cheaper place to live than other comparable Asian cities, with prime residential prices coming in at $2,850 per square meter. That is around 10% cheaper than luxury housing in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, which appears unjustified. The two cities have similar problems with heavy smog, gridlocked traffic and kidnappings. But Manila’s Makati district is an oasis of calm roads and pleasant shopping districts—surrounded by armed guards—whereas Jakarta’s high-end condominium towers provide no such respite from the difficulties of living in the city.

The Philippines has real weaknesses. Poor infrastructure makes the country, and its economy, highly vulnerable to natural disasters. Outsourcing, while a beacon of success, only provides around 1% of jobs in the country. The nation is yet to develop a viable export sector. And while it sits on abundant natural resources, the mining industry has been hobbled by corruption.

But Aquino is spending more on infrastructure and has placed a freeze on new mining projects while he grapples with how the state can obtain a bigger share of the industry’s revenues. It is easy to see why his presidency has sparked a long-overdue bout of optimism about the Philippines.