It takes less than ten people to assemble the famous pink printed edition of the Financial Times. The “carbon-based” team recycles the editorial produced all day long by the 600-person newsroom—with some deadlines adjusted to fit the newspaper’s closing.

The Financial Times has gone much further than many of its peers in digital transformation. That fact paid a critical role in the stunning premium paid by the Nikkei. When discussions started, Springer came with a first bid around £600 million ($930 million, €848 million.) The German media conglomerate later sweetened its offer to £750 million ($1.16 billion, €1.05 billion) before being outbid by the Japanese group.

As Ken Doctor noted in his Nieman Lab piece, based on the estimated operating income of the FT Group, Nikkei paid “a 43x multiple, or a price ten times what an average US daily, large or small, would sell for today.” (The actual ratio, though, is closer to 35x, but Ken Doctor removed the profit made by The Economist, which is not part of the deal.)

Jennifer Saba, in Breakingviews, also notes that publicly traded European media companies trade at 12x earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), and that Nikkei shelled out roughly twice the amount paid by Jeff Bezos to acquire The Washington Post in 2013. While such ratios might be above the assumed price of news properties, they’re still way below the multiples observed for tech companies (in many instances, there is no ratio at all because there is no profit, sometimes not even revenue).

Then let’s give a closer look at the two components of FT’s valuation: its digital reach and the power of its brand.

Over the last years, the FT has not deviated from a digital strategy based on limiting as much as possible its reliance on intermediaries. That idea was the basis for exiting the Apple application ecosystem, it required a massive investment in time and money to devise a proper solution. In Jan. 2012, the FT acquired Assanka, the developer of the first version of its HTML5 web app; it turned out to be a key asset in its strategy of independence. With its rebranded FT Labs, the FT.com was able to push the envelope for non-native mobile apps much further that its competitors who tried this avenue—often without assigning enough resources to succeed. This tech strategy worked fine even if the FT.com hit the limitations of HTML5 technology that didn’t entirely live up to its high expectations. Two facts remain: one, the FT was able to retain a precious direct relation with its digital subscribers, and two, it escaped Apple’s 30% fee (and the near failure of Apple’s Newsstand).

This no-middleman strategy was also implemented for corporate syndication sales. While the vast majority of its competitors go through third party vendors like Dow Jones’ Factiva or LexisNexis, the FT has been able to negotiate special deals, in which it keeps an eye on the corporate end user.

To sum up, the FT bet more on ARPU than on eyeballs. As opposed to first building an audience at all costs, and monetizing later, it assigned a stronger priority to growing its existing base, engaging the user in the best possible ways, retaining it and measuring its value in cash.

Vis-à-vis the advertising community, the FT played on the uniqueness of its brand, both prestigious and global. This allowed the FT to build on its affluent audience by preserving the daily and creating the How to Spent It luxury publication. The newspaper also resorted to a clever use of its data: one example quoted by FT people was a deal with a major airline that asked for an extraction of FT.com subscribers who regularly logged in from the airline’s overseas stops. The airline then targeted these readers, needless to say, with a premium campaign.

When it comes to ads, the Financial Times didn’t venture too much into the mass market. But that it needs to stuff its web pages with 50+ trackers (see our last week story on the matter) reveals a hesitant marketing strategy.

What’s next for the FT now owned by a Japanese media group?

First, there are signs of relief in the newsroom. Last week, the people I spoke with felt the organization will be better off with a Nikkei ownership than under Bloomberg or Thomson Reuters: the two news giants would have been tempted by the usual and brutal synergies. An Axel Springer ownership would have been a different story. It would have raised other issues such as EU coverage in which its half-controlled Politico.eu competes fiercely with the FT. And the British operation would have been run with tighter reins. Perhaps rightly so, the FT’s staff and current management believe the new Japanese proprietor will be very careful to preserve the company’s fabric. They do not seem concerned with the Japanese editorial culture of holding back punches when covering large corporations.

The big question is Nikkei’s willingness to further invest in the Financial Times’ development and to pursue its digital expansion. Pearson’s CEO John Fallon mentioned of an “inflection point” in digital media, suggesting that a push in mobile and social was required.

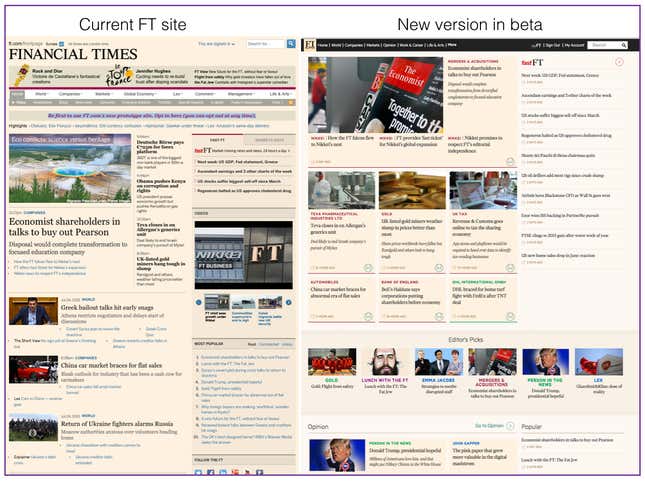

The company is currently working on a new version of its web site, see below:

Nothing revolutionary, but the site will be implemented in Responsive Design (RWD), a much-needed move to make the FT more readable on a broader variety of devices.

Beyond a general refresh, the scope of the FT’s modernization is hard to predict. As one staffer suggests, it won’t be worse than Pearson’s attitude that tolerated developments as long as they were supported by the publication’s cash-flow. In its coverage of the transaction, the Economist (also now officially on the block) mentions two important elements: the print culture is very ingrained in Nikkei’s universe, with digital subscribers accounting for only 16% of the 2.7 million circulation of its flagship publication, vs. 70% for the FT; plus, notes The Economist, Nikkei is funding the acquisition mostly through debt, which might no be the best context for the investments needed to support aggressive developments.

One final question: does the FT sale signal a new standard for evaluating large, legacy media brands? When it comes to The New York Times, FT’s ratios offer fresh hope: The Grey Lady’s current market capitalization is $2.2 billion, but based on the FT transaction, whether operating income or revenue are considered, it should be valued twice as much. Today, it seems Wall Street inflicts a discount on the NYT Co. due to the size of its print operations, an ever eroding circulation and the burden of 64 printing plants.