Uber’s security chief talks passenger safety, driver background checks, and California critics

Uber’s regulatory challenges in cities the world over have involved battles over the company’s impact on street-hail cabs, its contribution to traffic congestion, and its treatment of drivers. But perhaps no issue is more potent than one that’s still on the docket in many jurisdictions: passenger safety.

Uber’s regulatory challenges in cities the world over have involved battles over the company’s impact on street-hail cabs, its contribution to traffic congestion, and its treatment of drivers. But perhaps no issue is more potent than one that’s still on the docket in many jurisdictions: passenger safety.

Incidents in which Uber drivers have assaulted passengers, though rare, have invited additional scrutiny from many regulators. Sexual attacks by drivers in Boston this year and New Delhi last year tested public sentiment toward a company that often wins over consumers in its conflicts with local governments.

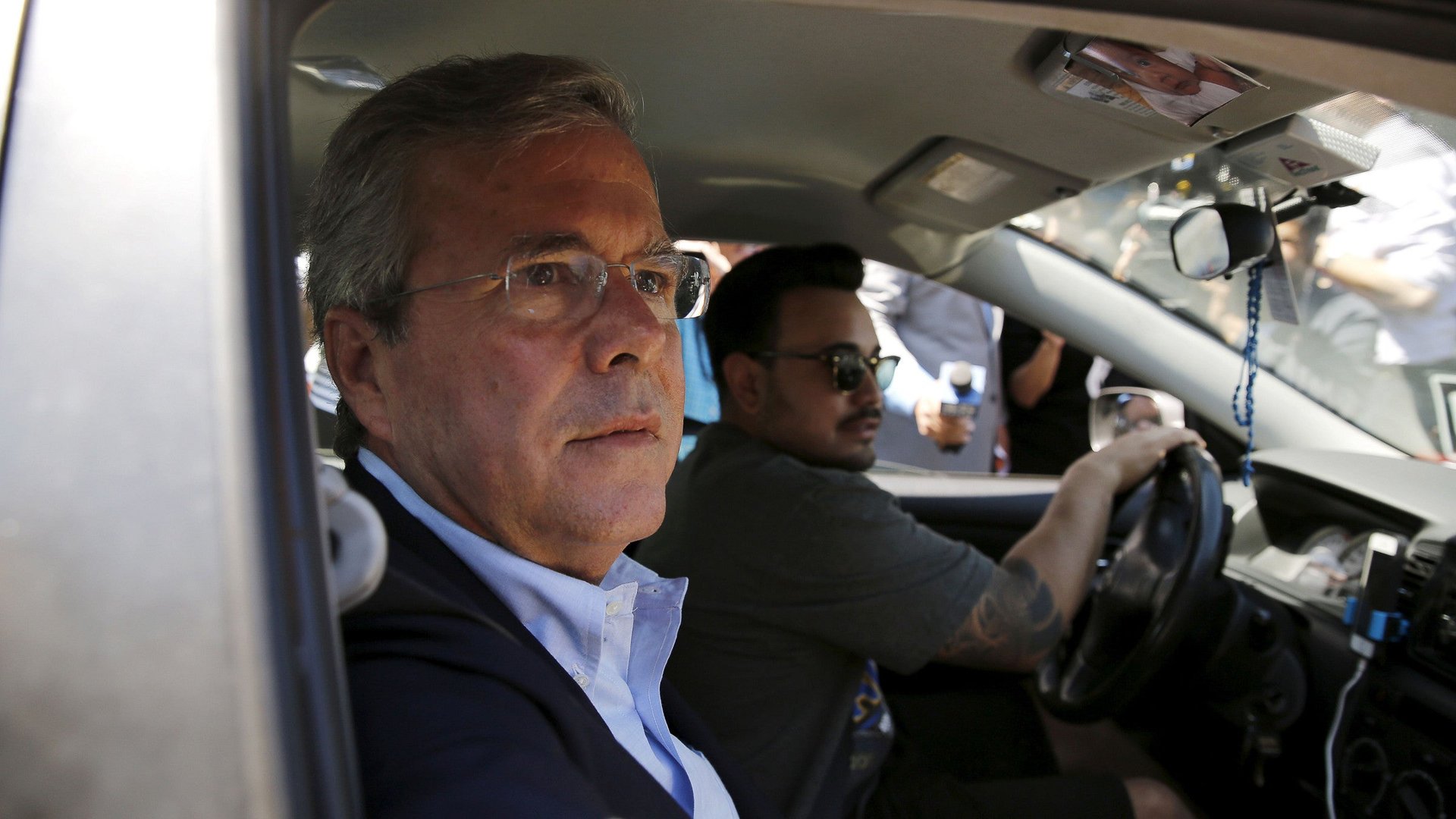

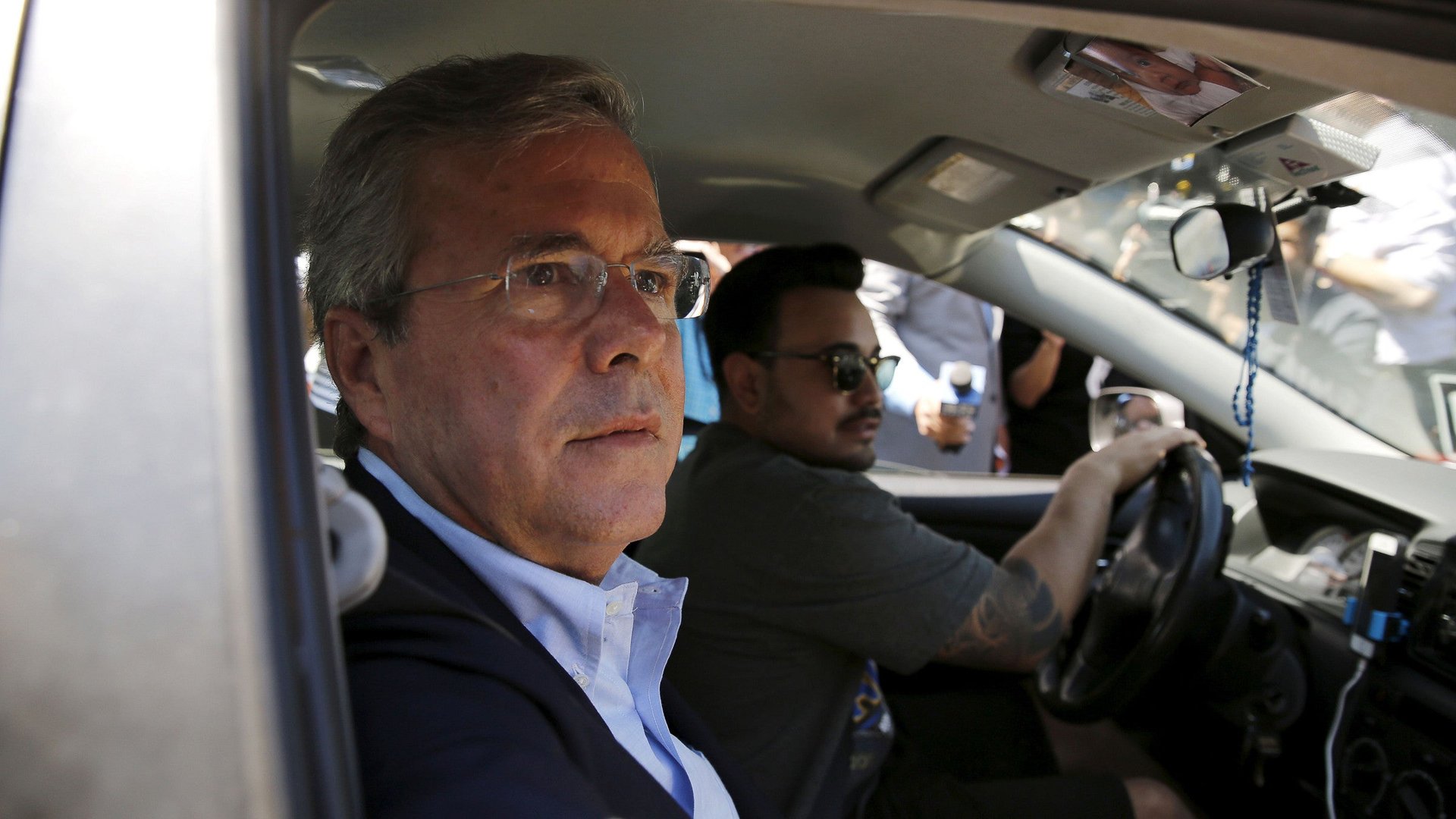

The executive responsible for Uber’s security issues is Joe Sullivan, a former US attorney who worked at eBay and Facebook before becoming Uber’s top safety manager in April 2015. In a wide-ranging interview with Quartz, he talked about why Uber’s security practices vary by market, and made the case that safety measures taken by the app-enabled car service are just as good, if not better, than that of entrenched competitors.

The latter topic is becoming increasingly important in California, Uber’s home state and one of its largest US markets. Taxi companies and local prosecutors there have sued the company for advertising claims about safety that they say Uber can’t back up, and state legislators have proposed a new law that would force the company to drug test its drivers and adopt a fingerprint screening system already used by other California taxi and limousine companies.

The practices that the legislature would like to see Uber incorporate into its background checks—both difficult to perform reliably on a mobile phone—would likely increase the cost of Uber’s security procedures. But Sullivan says Uber objects to the measures on other grounds, questioning their accuracy and arguing that they wouldn’t make passengers safer.

Moreover, since Uber lets taxis and livery cars use its platform, the company is able to show that non-Uber drivers have red flags of their own when it comes to their records.

In 2014, Uber said 475 licensed livery car drivers in California applying to drive for Uber failed the company’s criminal background check, including 14 applicants with sexual offense records, 37 with DUIs, and one with a record of attempted murder. In the same year, 600 taxi drivers in San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco who applied to use Uber’s platform failed the background check, including 19 with sexual offense records, 36 with DUIs, and 51 with histories of assault or battery.

As for the Livescan fingerprinting system that legislators are pushing Uber to use, Sullivan, a former US attorney, says that fingerprints may be smudged or change over time, and that technician errors might result in false negatives. He also says the Livescan system discriminates against people who were fingerprinted after being arrested but never charged or convicted of a crime, including a disproportionate number of black Americans. That may raise more hackles about the company’s racial politics, but Uber isn’t the only critic of Livescan’s system.

Even without Livescan, Sullivan—who recently outlined the company’s California safety policies in detail as part of Uber’s request for approval to pick up passengers from the San Diego Airport Authority—says that while no system is perfect, he believes his “stacks up well” against those of Uber’s rivals.

The company requires drivers to provide a full dossier of personal and vehicle information, including social security number and photographic identification. Then it hires two background-check firms commonly used by major corporations—Accurate and Checkr—to scan multiple databases, including the National Sex Offender Registry, the National Criminal Search, federal terrorist databases, state criminal records, and motor vehicle registration records.

Any potential driver who has committed a serious crime or been involved in a fatal accident in the previous seven years is disqualified; in addition, any driver whose license has been suspended or revoked in the previous three years is disqualified. There also are disqualifications for drivers who have had multiple traffic violations or accidents in the previous three to five years.

These timelines led to criticism after Uber drivers pulled over by police were found to have had criminal records predating the seven-year limit, but Uber says California’s state legislature set that time limit for criminal background check expiration.

Sullivan, who made his name at eBay building trust for economic transactions between people on the internet who never meet physically, says some of the same lessons can be used at Uber to ensure the person who signs up for the app is the person driving the car. This hasn’t stopped critics from arguing that Uber’s reliance on drivers to provide their own personal information—instead of using biometric data—invites fraud. But Sullivan maintains that Uber’s platform is naturally safer than traditional, street-hail taxis, because drivers don’t carry cash, passengers don’t wait on corners, and both parties are rated after each ride.

Beyond those basics, Uber’s security measures are adapted to each jurisdiction.

“The way to do safety varies based on where you are doing business—with 300 cities around the world, there is not one cookie-cutter approach,” Sullivan said. ”In the US, we do background checks; in other countries you don’t, necessarily.”

When Quartz reporters followed up on Uber driver training after the 2014 assault in New Delhi, the company declined to answer questions about its background checks there. In India and other countries, Uber has faced difficulties implementing background checks due to the lack of a central data repository.

“In other places where we don’t have as good background checks, we are testing psychological profiling and multi-factor authentication, different ways of screening driver’s licenses,” Sullivan said.

He notes Uber’s founder and CEO, Travis Kalanick, is e-mailed every time there is a safety incident. He says that when Kalanick was wooing him away from Facebook, he framed the car service’s safety issues in this way: “The challenge we have is that a safety incident can be a one-in-a-million thing, but we do a million rides a day. With the law of large numbers and the risks in vehicles moving in busy streets in urban environments, we’ve got to get really good to start changing the numbers.”