China’s WWII victory march plans are clashing with falling markets and Tianjin

China’s woes have been mounting. First, there was the devastating chemical explosions that rocked Tianjin a fortnight ago, then an equally devastating market tumble on “Black Monday” that has raised bigger questions about the depth of the country’s economic slowdown. But what China’s leadership appears to be focused on right now is a massive military parade.

China’s woes have been mounting. First, there was the devastating chemical explosions that rocked Tianjin a fortnight ago, then an equally devastating market tumble on “Black Monday” that has raised bigger questions about the depth of the country’s economic slowdown. But what China’s leadership appears to be focused on right now is a massive military parade.

The parade, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, will take place on Sept. 3, a newly created holiday to celebrate the allied forces victory over Japan. While Europe’s (arguably mostly successful) post-WWII reunification strategy might be summed up as “don’t mention the war,” in Asia unifying forces have lost out to rising nationalism in recent years. China’s plans to commemorate the “War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression as well as the World Anti-Fascist War” will be Xi Jinping’s first non-National Day parade since being declared president.

This “dwell on the war” strategy hasn’t sat well with most of the rest of the world. On Aug. 25, the Chinese government released a list of the 30 world leaders that will attend the parade. Except for South Korea’s Park Geun-hye and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, the others attendees are from small, not very powerful countries. And South Korea’s Park may not even attend.

Nonetheless, over the weekend, Beijing held a full dress parade rehearsal of 12,000 soldiers and over 500 pieces of military equipment—many brand new—from the People’s Liberation Army. The rehearsal showed 17 foreign armies are to march in the parade, but like the attendees, except Russia, they are not major world powers—other participants include Kazakhstan, Mexico, and Cuba.

The Chinese government is also considering amnesty for criminals who fought against Japanese invasions in WWII. But it has also rolled out a long list of public controls, from traffic restrictions in Beijing to online censorship nationwide, that are irritating its own citizens.

Will the parade burnish Beijing’s image at home, and inspire patriotism abroad? That remains to be seen.

The Forbidden City

The capital’s residents are finding that Beijing itself is more like a forbidden city than ever before in the run-up to the parade.

During last weekend’s rehearsal, they were inconvenienced by the shutdown of roads, railway stations, and shopping streets, and a ban on hotel reservations and art events. The same restrictions will be in effect again on Sept. 3. Besides the city’s two airports, some public parks, wireless internet, and radio signals near the parade site will also be shut down on that day.

Beijing has banned aerial activities including light-weight helicopters, gliders, hot air balloons and aerostats from Aug. 22 to Sept. 4, state-run news agency Xinhua reported.

There is even a ban on drone sales. Leading domestic drone maker DJI said on China’s major e-commerce platform JD.com that it has suspended drone sales (link in Chinese) in Beijing from Aug.1 to Sept. 3 in accordance with city aviation regulations. Other drone sellers on JD. com have also cancelled deliveries (link in Chinese) to Beijing, without specifying any reason. Alibaba’s e-commerce platform Taobao posted an announcement (link in Chinese) to halt all drone sales on the website though some shop owners still offer the service. The sales ban is so extreme that you can’t search for the word “drones” on either website.

Anonymous package deliveries are also forbidden in the city. From Aug. 20 to Sept. 12, senders and receivers of packages in Beijing are required to register with post offices and courier companies using their real names, Southern Metropolis Daily reported (link in Chinese). All packages will be scanned for security reasons. Tibet is the only other region that has the same restrictions.

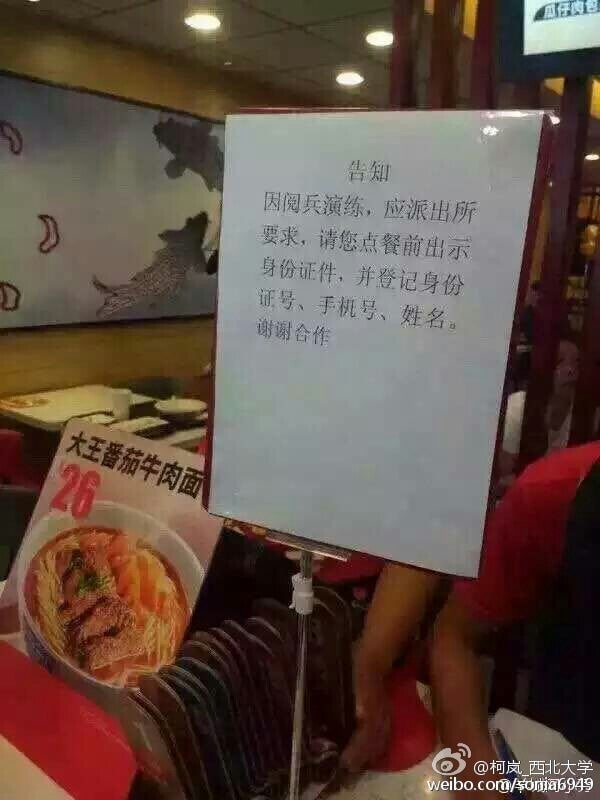

The “show your ID” policy is being rolled out in small businesses like restaurants as well. Pictures posted on Twitter-like Sina Weibo show signs from Beijing restaurants asking people to present ID cards before ordering.

The Beijing government has mobilized 850,000 citizens to patrol the city to ensure safety ahead of the parade. They will be sent to “every street, every alley” to look for signs of ”security hazards” and report them to police.

The restrictions have dampened enthusiasm for the parade itself in China. “Don’t come to Beijing during any event. You won’t know how long it takes for a safety check.” One blogger commented on Weibo.

Parade blue

Beijing’s noxious air pollution is not impossible to clean up, as residents have learned before—it all really depends on the government. In the past, Chinese officials have ensured a blue sky for foreign leaders, but not for its own citizens, turning skies “APEC blue” ahead of the economic conference.

Now, the goal is being called “Parade blue.”

Starting on Aug. 20, private vehicle drivers will alternate days they can use Beijing’s roads, based on whether their license plates end with even or odd number. Most government vehicles are also banned entirely. Starting Aug. 28, some 10,000 factories will be shut down or reduce production, and over 40,000 construction sites will be closed in Beijing and its surrounding provinces, Chinese financial media Caixin reported.

These goal is to reduce emissions of major air pollutants by 40% in Beijing and 30% in nearby areas compared to the same period last year, Beijing’s vice mayor told Caixin.

The People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s leading mouthpiece, posted pictures of Beijing’s recent blue sky and credited it to the government’s new measures on Twitter-like Sina Weibo (link in Chinese).

But the post has only invited huge public criticism. As one blogger commented, “it’s nothing worth showing off” and instead “we should feel sad about it.” Another blogger wrote (link in Chinese): “Instead of Parade blue or APEC blue, I hope there will be a Beijing blue in the future.”

Censorship nationwide

The Chinese government has handed out censorship instructions related to the military parade to homegrown websites, according to China Digital Times, a news site affiliated with the University of California, Berkeley, that monitors China censorship.

Leaked instructions from China’s top internet watchdog order all websites to review all news and comments related to the parade until Sept. 5 before posting, to guarantee nothing will attack the Communist Party or the army. It also ordered all websites to “promote positive, sunny netizen commentaries.”

Big Internet companies including Sina, Tencent and Baidu, as well as some more outspoken media outlets including financial media Caixin and state-run digital publication The Papers are also named in the instructions. These companies must report the names and the contact information of auditors who supervise the websites’ online contents, daily.

And Beijing is reportedly cracking down on virtual private networks, which allow internet users to bypass censorship by giving them an ISP address outside the country.

TV programs have been carefully chosen. The state’s broadcast watchdog has ordered TV stations to suspend broadcasting entertainment programs including talk shows, reality shows and TV series from Sept. 1 to 5. Instead, national broadcaster CCTV, along with some provincial TV broadcasters, will air “special programs” on the war against Japan instead, the Beijing Youth Daily reported (link in Chinese). Of course, CCTV will air the parade nationwide on the morning of Sept. 3.

Last month, the Chinese government said it will shut down the stock market on Sept. 3 and 4 for the new holiday. This state-mandated trading halt could prevent the stock market from falling further, and distract the public by whipping up anti-Japanese sentiment, as Quartz has noted.

China’s internet users joked that retail investors—with green caps, representing the color stocks turn on China’s market boards when they drop—should march in the parade, because they’ve used their hard-earned money to save the market for the country.

A week ahead of the big event, there’s plenty of positive comments online, like this on Zhihu (link in Chinese), a Quora-like question and answer messaging board:

A powerful country will never treat others’ homelands as weapon testing grounds, but it will display its modern weapons on the capital’s square and tell the enemies: Dare you come, you will have little chance of returning.

But it is impossible to tell how many of those come from China’s “50 cent party,” the internet users paid to post pro-government comments. And plenty of China’s citizens sound deeply cynical about the event.

“It will let your blood surge, and you will forget about your pay stub and prices [of food and goods] for a moment,” one blogger wrote about the meaning behind the parade on Zhihu.

“It’s an enthronement that wastes manpower and money,” another blogger wrote on online forum Tianya (link in Chinese), describing the parade as as effective as “injecting chicken blood,” a form of medical therapy popular in China during the Cultural Revolution. Still, he predicted, “it will make the flunkies feel one climax after another.”