3D printing seems to be finding a niche in medicine. The latest feat: Two weeks ago, doctors implanted a 3D-printed titanium sternum and ribs into a patient in Spain. According to CNET, he’s doing well.

The patient is suffering from a form of cancer that formed tumors in his chest cavity. To get rid of them, doctors at Salamanca University Hospital needed to cut out a section of his ribs, along with his breastplate. Often, doctors would replace the ribcage with a flat piece of titanium—which can actually loosen over time—but 3D printing allows for a more customized implant. The team at Salamanca took CT scans of the patient’s ribcage and used those images both to show surgeons exactly where to cut, and to create a 3D model to print replacement parts.

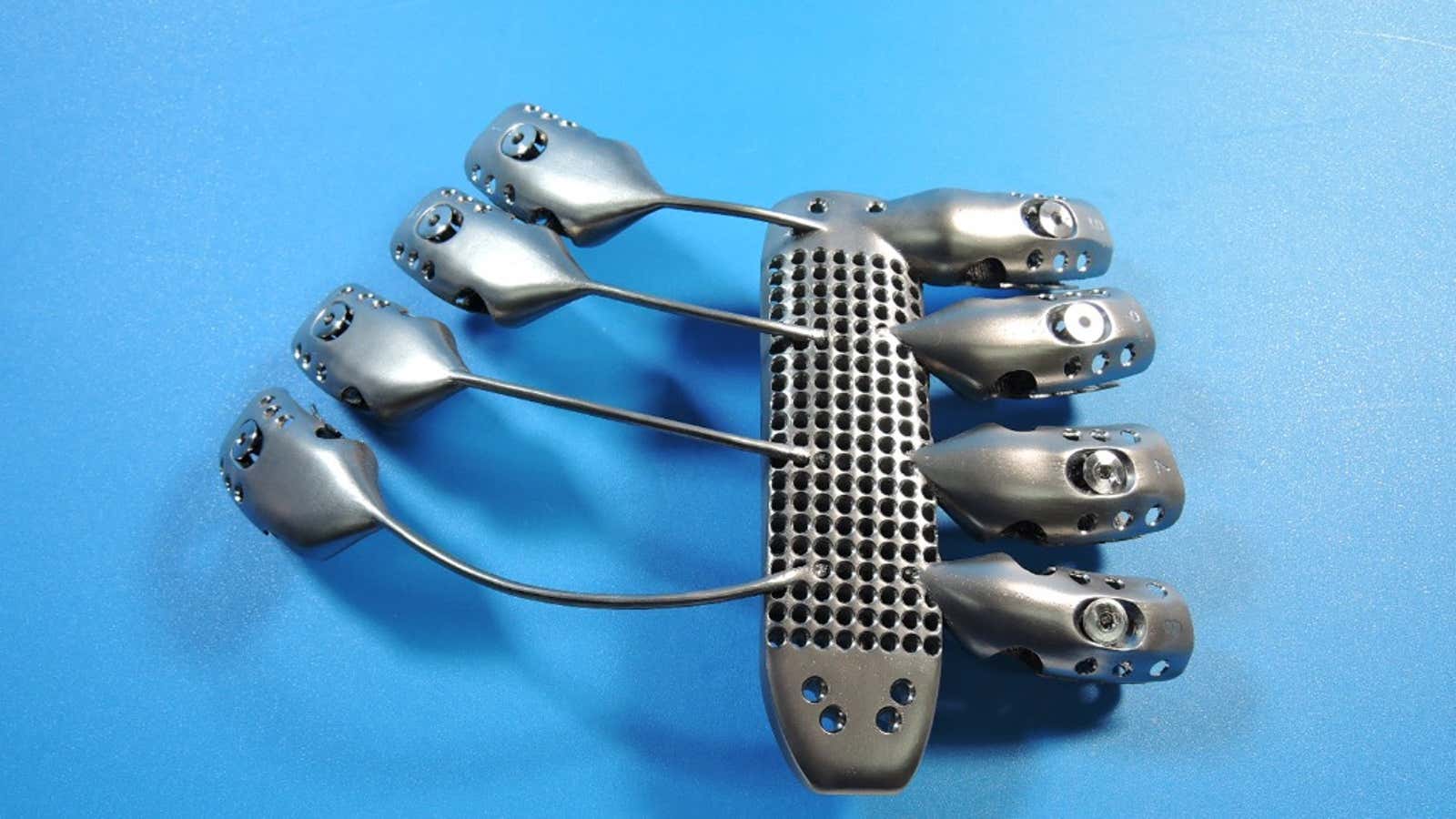

The team contracted Anatomics, an Australian medical company, to figure out how to print the file. Anatomics sent the 3D files to the Australian government’s 3D-printing lab at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). The lab’s printer prints by using a high-powered electron beam to melt metal powder into layers. The result was a titanium object that looks less like ribs and more like something you’d see in a car’s engine, and fit perfectly into the patient’s ribcage.

Beyond being able to create truly personalized solutions to medical problems, 3D printing allows doctors to rapidly prototype ideas. In the US, doctors are using 3D printing to produce models for doctors to inspect and figure out the best plan for surgeries, without any invasive biopsies needed. Researchers are also working on 3D-printed tissue implants, but those haven’t been approved for use in humans yet. 3D printing, however, has started to make some regulatory inroads in the US. Last month, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first 3D-printed drug for consumption, and the FDA is researching more safe ways to bring the technology into the human body.

3D printing, especially in medicine, is still in its infancy. The Salamanca team’s achievement may well pave the way for more 3D-printed parts in humans, and perhaps America’s obsession with elective cosmetic surgery may one day extend to 3D-printed improvements. Hopefully no-one tells the Canadian government.