An uncommonly strong euro is making European exports expensive—dangerously so for the continent’s weaker economies. So what’s the solution: Depress the euro, or force countries to do possibly painful things to make their exports cheaper?

French president François Hollande thinks it’s the former. He said today that he wants the euro zone to “decide on a medium-term exchange rate” and trade on global markets to meet that rate. German economic minister Philipp Roesler disagreed, saying that “the objective must be to improve competitiveness and not to weaken the currency.”

That forking of views looks a lot like their countries’ respective economic performances (best captured in this chart from Markit Economics). A slew of data out today reaffirmed the widening gap between Germany and almost everyone else in the euro zone. While Germany’s service-sector PMI rose to 55.7 from 52.0, the business activity in France, Italy and others declined markedly.

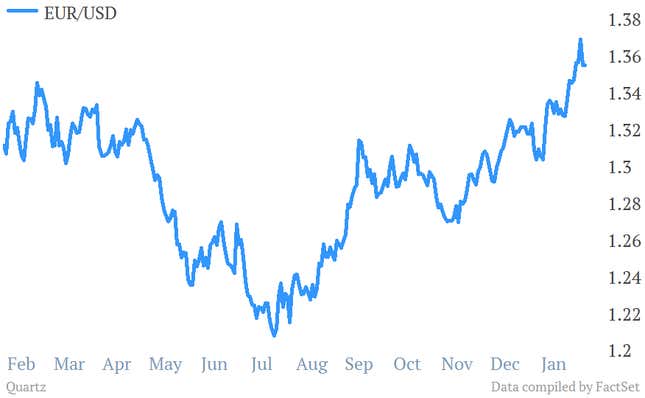

Fazed not at all by this divergence, the euro rallied again today. Here’s a little more historical context on its ascent:

One big reason that the euro continues to gain is that many doubt its current strength will actually hurt the economy, says The Wall Street Journal. While BofA Merrill Lynch Global Research puts only 6% of company earnings growth down to currency fluctuations, the global business cycle and credit availability determine three-quarters of that growth, according to the Journal.

But neither of those is all that rosy—and both are intertwined with the euro’s strength.

First, the global business cycle. The good news is that export demand picked up a bit in January. But sluggish domestic demand continues to be a problem. Economist Phil Smith of Markit Economics says these trends are currently at play in Italy.

“With regards to exports offsetting some of the downturn in domestic demand, I think we are currently seeing this to some extent. January manufacturing PMI data did indeed show a positive trend in exports over the month,” Smith tells Quartz. “But that brings us to … the rising strength of the euro, continuation of which will hurt Italian exporters’ competitiveness outside of the euro area.”

Regardless of how much global business picks up, none of the euro zone members would benefit from a stronger currency. But it would affect some more than others. For instance, France’s exchange-rate sweet spot (paywall) may be around $1.22, while Italy’s is more like $1.16.

Then there’s the European Central Bank’s incredible shrinking balance sheet. As we explained last week, this is tightening in all but name and implies a worrying slump in demand for credit. But while this is probably bad for euro zone businesses, it’s likely propping up euro confidence—which is, in turn, threatening the modest export rebound.

So the currency’s surge is exacerbating the gap between rich and poor countries in the euro zone. But hardly anyone expects that worry to sway the ECB when its Governing Council announces monetary policy on Thursday.