The evidence that Asia is throwing off its dependence on the West

As Western economies struggle to return to growth, Asian countries that used to depend on trade with Europe and the US are turning to the rest of Asia instead. The forthcoming ASEAN Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) would essentially link the up-and-coming Asian producers of ASEAN (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) to the region’s consumers, the more developed economies of Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. Negotiations about the single market are set to start in April, with plans for putting trade partnerships in place in 2015.

As Western economies struggle to return to growth, Asian countries that used to depend on trade with Europe and the US are turning to the rest of Asia instead. The forthcoming ASEAN Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) would essentially link the up-and-coming Asian producers of ASEAN (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) to the region’s consumers, the more developed economies of Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. Negotiations about the single market are set to start in April, with plans for putting trade partnerships in place in 2015.

This isn’t a new trend, but there are signs that it’s intensifying. Shippers are cutting capacity on routes from Asia to Europe, and—as we’ve noted before—some of that traffic has been diverted to the US. But not all of it, as it turns out.

The shipping industry has been overwhelmed by high capacity across the world, as ships ordered before the financial crisis finally hit the water. That—not to mention sinking consumer and business demand—has depressed rates on all trade routes. Shippers used to scuttle boats after 25-30 years, but now recycling yards are seeing ships that were built as recently as 1999 and 2000. This overcapacity will take years to be absorbed, and so shippers are forced to look for any bright spots they can to whether the storm.

The biggest bright spot is in Asia itself. Shippers have been expanding their offerings in intra-Asian trade, even as they cut ships from now unprofitable routes to Europe. Even when the time comes to scuttle a ship, Asia is a good place to do it: Cash buyers of old boats are selling everything from ships’ engines to the beds their crews use to sleep in to hungry consumers in India, China, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

United Parcel Service (UPS) announced a new route between China and South Korea in October, saying it has plans to do more. Both UPS and Fedex have been fighting for a bigger piece of the Asian shipping market, striving to make inroads into China and elsewhere while they still can. Asian trade was a key reason why UPS tried (and last month failed) to take over Holland’s TNT Express; the latter estimated that it would have boosted UPS’s market share from 16% to 28% in Asia. Not to mention that air traffic between Asian countries is on the rise. On Feb. 4, Australian airline Qantas announced that it would consider new flights to China, India, and South Korea.

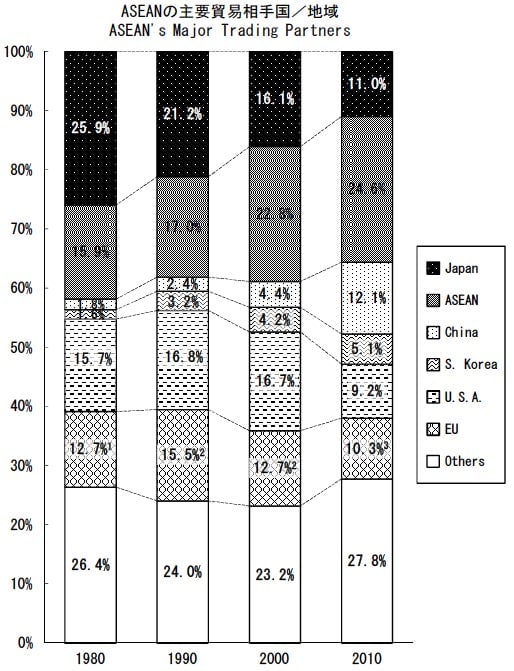

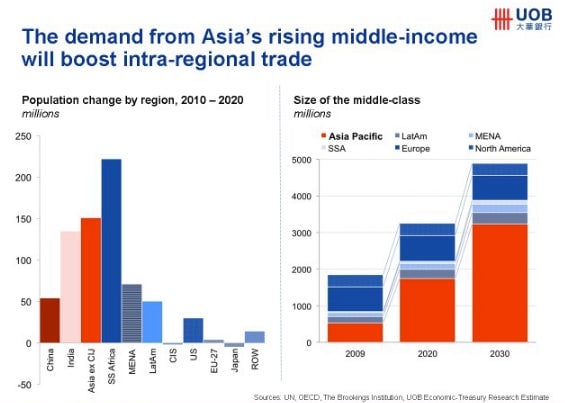

The driving force behind all this is a swiftly growing middle class in the region. As the figures below demonstrate, the sheer volume of future consumer growth will drive focus to Asia and away from slower-growing markets in the West. In 2011, 40.5% of ASEAN countries’ exports ended up in other ASEAN countries, China, or India according to data compiled by the United Overseas Bank. By 2020, the bank estimates, such exports will account for 51.0% of the total.

Even within the last few years—from 2008 to 2012 and through the great recession—the share of global market trading conducted within Asia has grown from 19% to 21%. Part of that is just because Asian populations are growing faster; but it’s also because consumer demand is surging in Asia as Europe and North America struggle to prop up growth.

That’s part of the reason why the US has been attempting to subtly marginalize new partnerships like RCEP. America fears that it will be left out of the party, particularly since China will likely wield strong influence in regional groups. The US is trying to set up an alternative group, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which excludes China and Japan but includes some American allies—Canada, Chile, Mexico, and Peru.

But although the partnership could be established by October of this year, it’s not clear how powerful the organization can really be. In addition to China and Japan, it leaves out budding economic powerhouses South Korea and Vietnam, among with smaller Southeast Asian countries. TPP’s backers may be missing a simple truth: The numbers suggest that as time goes by, what happens in the West will have less and less impact on Asia’s economic well-being.