When European or American publishers rant about the ad blocking plague, they tend to focus on browser extensions such as AdBlock Plus that eat a sizable part of their business. But the scope of the problem does vary with territories and demographics. At a European gaming site, 90% of users run an ad blocker, and a major German publisher recently stated that 40% of its monetization evaporated for the same reason. In the news business, roughly 30% of desktop users watch contents with no ads (see our past stories on the subject.) Last week in Dublin, at the DoubleClick Leadership Summit, where Google gathered a couple of hundreds of its advertising partners, 23% of the audience admitted using an ad blocker. The very same crowd that sells or buy ads eliminates them while browsing the web. Interesting.

As big as it already is, this might in fact just be the tip of the iceberg. The ad blocking picture in even more startling when considered on a global scale and when the mobile internet enters the picture. There, new players are staking strategic positions.

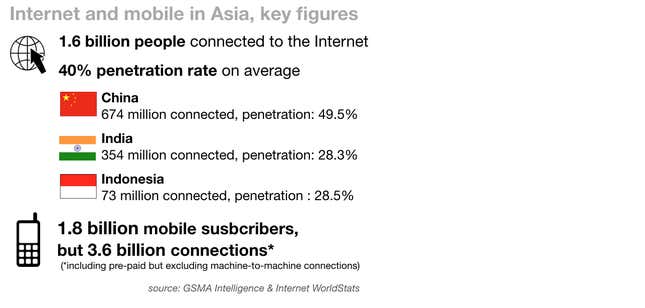

Let’s consider the Asian market structure:

In countries such as India, China, and Indonesia (altogether 1.1 billion internet users), mobile browsing is much more prevalent that in Western countries. As one of my interlocutors explained, new digital users often go online with smartphones that don’t have sufficient capabilities to accommodate a large number of applications. In addition, data plans are expensive. In Asia, owning a mobile phone eats about 5% of the average salary, vs. 1% or 2% in Western countries (where the data consumption is at least three times higher.) Once an Indian user gets a new phone, s/he won’t go online to get his apps but go to a local store that will connect the handset to a cable and load a small number of programs. The process is often repeated as churn rates are high in these markets.

These peculiar economics make the task of selling ads on mobile quite hard. As an engineer who works in Asia told me: “It’s difficult, especially if you consider local market conditions, prices [of ads] are so low that they can fall below the cost of the data that transport them…”

Hence the appeal of adblockers.

In India (and in most Asian markets), the number one mobile browser, UC Browser, commands a 51% market share, leaving its competitor in the dust (see below):

Here is the catch: UC Browser comes with an ad blocker set to “on” by default. This browser promises to consume 79% less data than its competitors… I installed it in on my iPhone: it’s fast, stable, and compatible with every site I visited.

Even more interesting, UC Web is part of Alibaba Group, the giant Chinese e-commerce site: with the the equivalent of $248 billion in revenue, Alibaba is bigger than Amazon and eBay combined. Hence the question: What is the number one e-retailer in the world doing in the ad blocking business?

It could be two things. One is that Alibaba sees ads as deteriorating the mobile browsing experience so much that they hurt e-commerce revenue. This makes sense: Google found that 49% of people leave a mobile web site if it takes longer than 6 to 10 seconds to load. The other reason could be that Alibaba wants to control the flow of advertising, to favor its own. Operating a largely deployed ad blocker means retaining a tight grip on ad filters, that is manipulate UC browser settings that selectively let “good” ads go through.

This happens to be the very model at the core ad blocking business Eyeo GmbH, the creator of AdBlock Plus. The company might say it puts the consumer first, but when an advertising player decides to pay up, Eyeo’s virtue yields to cash. This “selectivity” also was the case for some Google formats, and for absolute nuisances such as Taboola or Outbrain (the clusters of ads formats that sell anti-fat pills at the bottom of the gruesome account of a terrorist attack). The latest internet pollution to be white-listed by AB+ is Criteo—the retargeting company to which you owe ads still pursuing you because of the pair of sneakers you shopped for six months ago. According to the French website JDN, Criteo agreed to pay Eyeo for a right to be unblocked. That said, the companies that gave in to AdBlock Plus might end up being screwed anyway: as I write this, all of their URLs and scripts are still in the list of 44,000 filters maintained by AdBlock Plus—never trust an ad blocking company…

In some markets, the prosperous ad blocking cottage industry takes a particular form. At Google’s DoubleClick conference, I found myself on a panel with an interesting character named Roi Carthy, CMO of ad blocker Shine, a startup based in Israel.

Where Ad Block Plus is a Kalashnikov, Shine is a weapon of mass destruction.

Shine’s business is to suppress mobile advertising—all of it, to every customer—by simply eliminating ads at the cell phone carrier level. Pretty radical. As Roi explained, his approach is very straightforward: “We say to the cell carrier, look, 20% of your bandwidth cost goes to carry advertising. Our solution helps you remove this important part of your operating expenses…” When he makes his pitch to a “pure” mobile provider with no stake in the content or advertising side, Shine’s solution is given great attention.

This is the case for Digicel Group Ltd., a company headquartered in Bermuda, that bought Shine’s piece of code and removed all ads to… 14 million customers. Roi Carthy is good at wrapping up his opportunism in humanitarian considerations. “We are here to defend the customer. We come from the antivirus business,” invoking the national security dimension of Shine’s original activity. “Now we want to give the choice to the consumer”—except that by cutting off the ads at the source, Shine deprives the Digicel customer of any choice (let alone Digicel customers such as local businesses who might be willing to promote their products…). Shine grants itself the right to decide what a mobile phone user can see or whether a Jamaican business has the right to advertise. North Korea does that too.

“We should not underestimate Shine,” warns a Google executive, “they have traction; they recently got the former CEO of Vodafone Europe on their board of directors and more cell carriers are considering working with them.” He’s right. Among the presumed candidates are two major British cell carriers: O2 (23 million subscribers) and EE (27 million). Shine could become a big problem for the industry. Especially since fighting it will be difficult. The concept of net neutrality might have some traction in large mature markets such as Europe or North America, but much less so in Caribbean or South Pacific territories.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.