In July, Mario Draghi, head of the European Central Bank (ECB), promised that the bank would “do whatever it takes” to protect the euro. That set off a six-month wave of “risk-on” sentiment among investors in Europe. But it was based on dubious assumptions. Though the euro zone had made progress on joint banking supervision and rectifying fiscal imbalances between different countries, in reality most investors credited Draghi’s promise, and his program of “Outright Monetary Transactions” (OMT)—where the ECB pledged to support countries in trouble by keeping their borrowing costs down if they asked for aid.

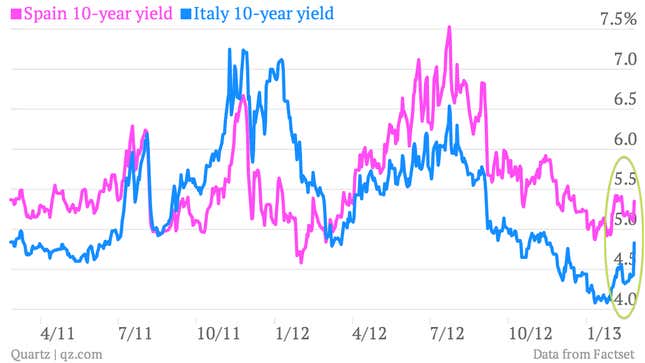

At the time, Spain was expected to request this kind of aid within a few months. But yields on Spain’s 10-year bonds—a measure of investors’ trust in a government’s ability to pay back its debts—which had topped 7.5% in late July before Draghi’s speech—fell sharply afterwards, as investors gained faith that the ECB would step in to save Spain if it had to. That belief meant Spain hasn’t had to ask for help. The same thing happened with Italy.

But Italy’s election result challenges those assumptions. As they did last year in Greece, voters have failed to do what investors thought they were “supposed to do.” Rather than support Mario Monti, the outgoing prime minister who tried to make Italy more competitive through austerity measures, and Pier Luigi Bersani, who would have continued much of Monti’s reform program, voters shifted much of their backing to the parties of former PM Silvio Berlusconi and Beppe Grillo, an anti-establishment populist. With a hung parliament or short-lived government in the offing, the fate of those reforms is unclear.

Greece and Italy mark a trend: Voters are moving away from career politicians whose top priority is European unity, and towards candidates who care (or claim to) that their populations are suffering now. Citi’s global head of FX strategy, Steven Englander, wrote in a note yesterday:

This is the first European election in which voters didn’t do the right thing. Instead they gave surprising support to politicians who reject austerity and, in some cases, the euro. This could become a major problem if it proves contagious.

Perhaps analysts shouldn’t be quite so “surprised” when voters “do the wrong thing” and reject crushing austerity measures whose long-term benefits are as yet nowhere in sight; but that’s another story. For the most part, though, investors are only cautiously bearish. They still believe that central banks will do enough to keep the euro—and the global economy—chugging forward.

In reality, however, there’s little reason to believe that the ECB will do anything but continue to sit on its hands for a while. Having refused to even cut interest rates as the European economy collapses, the ECB’s cards are already on the table. It will step in and help Italy or Spain if they ask, but Italy and Spain are not going to incur the wrath of the Germans—and take on the stigma of economic pariahs—by asking for help until they really have to. That means when things are a lot worse than they are now.

The ECB, in short, cannot stave off crisis; by the terms of its pledge, it will only act when the crisis has already exhausted a country’s alternatives. Actually carrying out OMT would probably inspire confidence that the ECB is living up to its promises and perhaps even a return to a “risk-on” environment. Until then, investors’ confidence might be living on borrowed time.