The European Central Bank (ECB) is keeping interest rates unchanged at 0.75%, it announced just now. While expected, this goes against the better judgment of most Keynesian economists. Not only does the move effectively strengthen the euro against its peers, making exports pricier. But it also counteracts the credit pressures still plaguing the euro zone right now, particularly in peripheral banks. The ECB is pretty much refusing to do anything more to allay the euro zone’s economic pain.

In effect, this do-nothing approach means the ECB’s balance sheet will contract, reducing the amount of money available, and thus tightening credit. That’s because European banks are returning the money they borrowed from the ECB last year. And while other major central banks continue to throw more cheap cash at their still struggling economies, the ECB remains the last bastion of conservative monetary policy. That leads to a stronger euro, which means that European exports are going to be more expensive in global markets.

Why, you might ask, does the ECB refuse to join the party? Cutting interest rates wouldn’t be considered a radical monetary maneuver. Unlike the (gasp) “unprecedented monetary policy” we’ve seen from the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, or the Bank of Japan, interest-rate adjustment is a fairly traditional move.

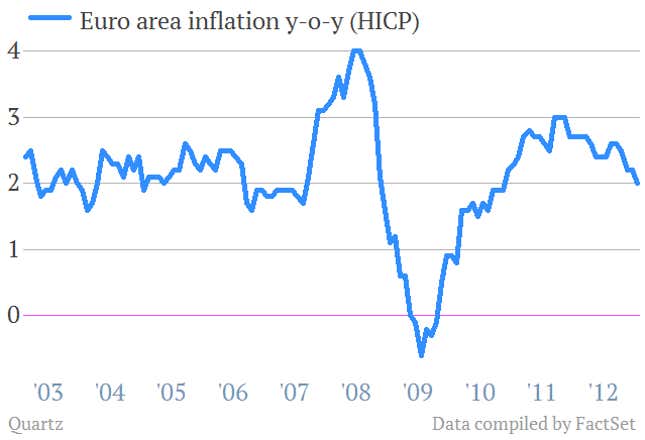

Its reluctance in large part is because the ECB—which is really subject to German influence—is irrationally freaked out about hyperinflation (we have Germany’s post-World War I experience to thank for that). Loosening the supply of money could indeed prove inflationary. But it’s hardly a secret that pressures on Europe are now decidedly deflationary, as the whole region is sinking once again into recession.

To be fair, the ECB is acting in line with its mandate. Unlike the Fed, which is responsible for addressing both inflation and unemployment, the ECB has but a single mandate: price stability (read: inflation). Its monetary policies are not even supposed to take the health of the euro area economy into account. And, okay, it may have stretched the interpretation of its mandate in its bid to keep the euro together and extend financial assistance to struggling countries and banks. And even, then the ECB has consistently stuck firmly to its mandate, jumping in only to avert the worst case scenario.

That it continued to do that today is grim news for most Europeans. But the ECB has told policymakers that it will do no more to staunch the crisis, and it’s making good on its word.