Over the last five years, Texas has resettled more refugees than any other US state, surpassing even the more populous California. That includes about 250 people from Syria—a significant proportion of the tiny number of Syrians who have been allowed into the United States since 2011, when the country’s harrowing civil war began.

Among them are Faez and Shaza, who live in Dallas along with their two baby daughters, trying to piece their life back together. Despite the recent rise in anti-Syrian political rhetoric, for the most part they have felt safe in Texas, where they arrived in February.

“People are not as prejudiced, not discriminatory against us,” Faez tells Quartz through an interpreter, via Skype. “It’s a very good place for us to be.” They asked that their last name not be used, due to fear for family members still in Syria.

But a recent shift in the political mood—including a vow by Texas governor Greg Abbott to refuse refugees “from this dangerous zone of Syria”—have made Faez and Shaza feel increasingly uneasy. They escaped Syria when Faez realized he “could be killed at any moment.” Now, they feel that their presence in the United States can be questioned by “any decision by anyone in the government.”

Being in America is still a huge improvement from living in Amman, Jordan, where they scraped by living in close quarters, without any documentation or possibility of legitimate work. Faez says “it was the worst time in [his] life.”

Refugees under fire

Even before Donald Trump’s incendiary remarks this week calling on the US to ban all immigration by Muslims, the mood toward Syrian refugees has turned hostile in the wake of the Paris attacks by ISIL, which left 130 people dead.

Abbott and more than 30 other governors, mostly Republicans, have said they would not welcome refugees in their states, and Congress voted on two separate bills to slow down or block the Obama administration’s plan to admit 10,000 Syrians.

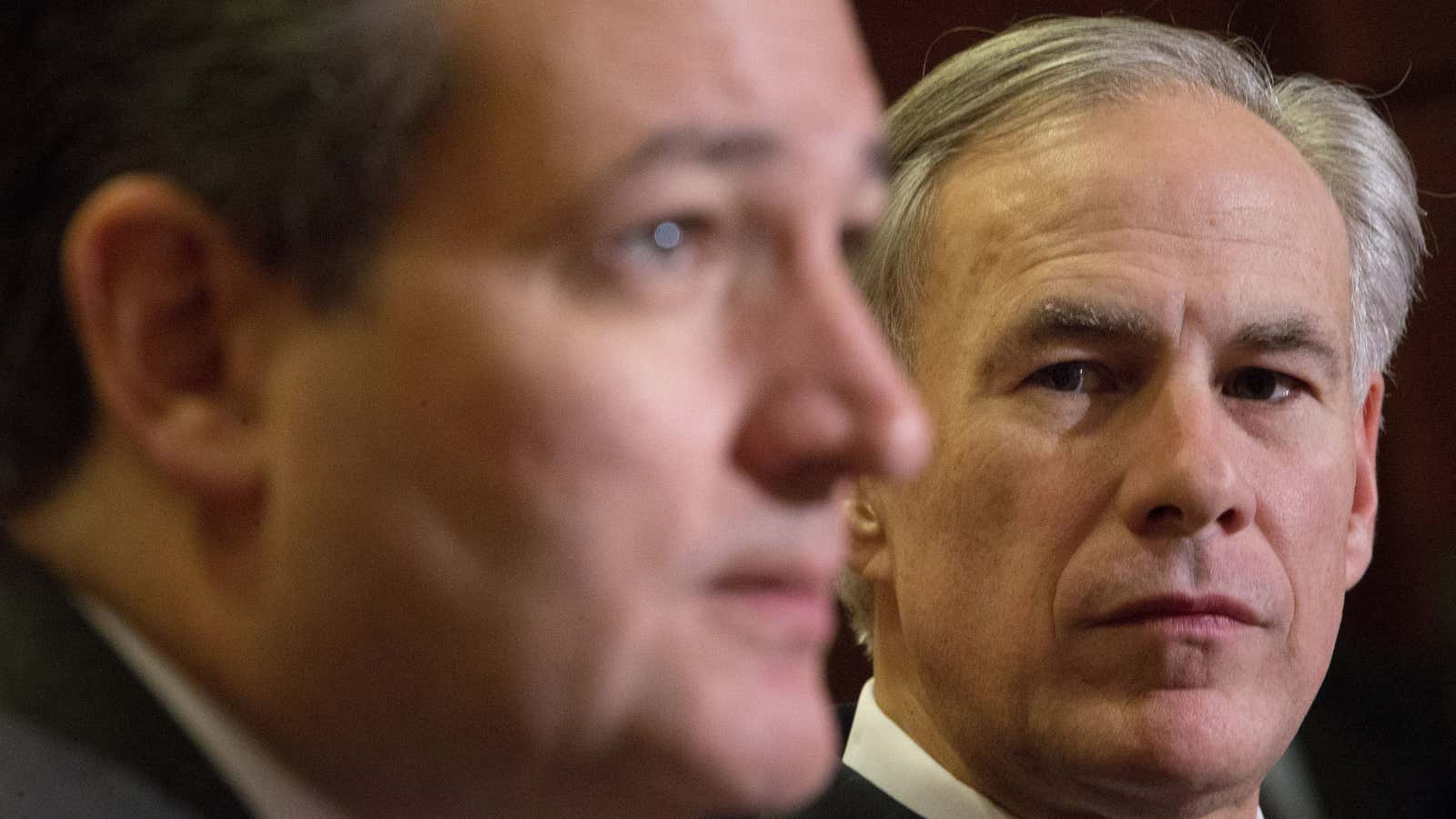

Abbott is now teaming up with Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, who is in the midst of a campaign for the Republican presidential nomination, and is finally gaining traction in the polls. Cruz, whose own father, born in Cuba, received political asylum in the United States, is introducing a new bill that would allow states to opt-out from taking in refugees. Asked for comment, the governor’s office referred Quartz to his previous media appearances, including a press conference alongside Cruz.

The International Rescue Committee (IRC), which helped with the resettlement of Faez and Shaza, has defied an order by Abbott to stop processing Syrian refugees. That prompted a lawsuit by the state against the IRC and the federal government, which alleges that the government and other agencies broke their obligation to consult regularly with the state on refugee resettlement.

Denise Gilman, law professor and director of the Immigration Clinic at the University of Texas Law School tells Quartz that the state has no legal basis for its claims, and that the motion “has to be understood only as a political message.” Sure enough, the federal government struck back with a court filing on Friday (Dec. 4) that picked apart the state’s claim, concluding that Texas had no right to refuse refugee admissions.

Texas withdrew its request for a temporary restraining order (TRO) for resettlement, but it has not dropped the lawsuit and is seeking an injunction.”Our state will continue legal proceedings to ensure we get the information necessary to adequately protect the safety of Texas residents,” Ken Paxton, the state’s attorney general said in a statement. Paxton filed another TRO request on Wednesday (Dec. 9), and was promptly rejected by a federal judge. “The [Texas Health and Human Services] Commission argues that terrorists could have infiltrated the Syrian refugees and could commit acts of terrorism in Texas. The Court finds that the evidence before it is largely speculative hearsay,” the court wrote.

The IRC would not comment on the lawsuit or the impending legislation. “We understand the issues and concerns of the governor and we are trying to address them to the best of our ability,” said Donna Duvin, executive director of US programs in Dallas, underlining how successful Syrian refugees have been with settling in and ”becoming contributing members of the community.”

Experts say Texas has been fighting a losing battle from the very beginning. Admitting refugees lies solely in the purview of the federal government, and states cannot legally refuse to accept immigrants. Refugees are also protected under the 14th amendment of the US constitution, which prohibits discrimination based on nationality, Gilman says. What’s more, she points out, there’s the basic fact that the US has no internal borders, so states can’t ban any group from entering once they are legally in the country.

Faez rejected any fears that terrorists could sneak into the United States by posing as refugees from Syria. The refugee screening process in itself is long and arduous, often taking up to two years, and refugees are the most scrutinized population coming into the United States.

“They know everything about you when you come to America,” he said.

When rhetoric doesn’t match the record

Texas’s vehement refusal to accept Syrians could stem—in addition to the stated security concerns—in part from the state’s traditional independent streak, and in part from partisan politics.

States’ rights are a battle call in the Lone Star state, championed by its governing elites and representatives in Washington. Fighting the feds could in part be the reason for the state’s adamant opposition to accepting refugees. But it’s not quite that simple, says Gilman. The traditional tension is exacerbated by a Republican governor and a federal government run by a Democratic administration.

“When [Abbott] was attorney general made very clear that he saw a very important part of his job as waking up each morning and trying to sue the federal government,” she adds. During his campaign for governor, he boasted about filing 30 lawsuits against the Obama administration.

But the antagonism toward refugees by Texas politicians does not match up with the state’s welcoming record. Texas has admitted more than 100,000 refugees over the past two decades, according to figures provided to Quartz by the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

In the past five years, its tally has surpassed any other state, with most of its refugees coming from Myanmar, Iraq, and Somalia.

One reason for Texas embracing those fleeing their own countries is the state’s sheer size: It is the second-largest state by population and square mileage, and so has the capacity to accommodate more people. There are also a number of non-profits helping refugees in the resettlement process, which creates a large support system.

But there’s another aspect—an economic one. “For the most part, Texas communities have seen it to be a huge benefit to bring refugees in, an economic motor and a real opportunity for building the social fabric of these communities,” says Gilman. Duvin says the IRC has been overwhelmed with requests from Texans seeking to help the resettled families.

There are also many Texan cities where working hands are badly needed, and the refugees come in pre-screened, fully documented, and eager to work. One such place is Nacogdoches, where a chicken processing plant said it would hire several hundred refugees from Myanmar in 2011. With a low unemployment rate, and a lack of manpower to perform tasks such as de-boning chickens, the community welcomed the newcomers, NPR reported.

“They are truly willing to assume some of the jobs that typically have a high-turnover and the refugee employees tend to stick with them a little bit longer because they are so happy to be employed,” Duvin says. She said that a number of employers, especially from hotels and restuarants such as Chipotle, routinely reach out to the IRC looking for potential employees.

Faez, who had studied political science and worked in the healthcare system in Syria, currently stocks shelves in the frozen foods section of a Dallas supermarket. He doesn’t like the job much, but hopes to continue his education in the future, as does his wife.

“Right now, what we’re focusing on the most is financially supporting our children, our daughters,” says Shaza.

The family did not choose to be in the US; they were supposed to go to Europe, but were reassigned by the United Nations. Most Syrians surveyed by Gallup in January, said they wanted to go to Europe or other Middle Eastern countries. Only 6% preferred North America.

Most of all, Shaza and Faez want to be back in a peaceful Syria. Asked what they would tell their daughters about Syria, the couple is visibly moved. “I’ll tell them that it doesn’t matter how long we’ve been here, that’s our home. Our home is more beautiful, that is where our roots are,” says Faez, as Shaza wipes her tears.

Every day, they think about their loved ones who have died in the war. Watching news of the Paris attacks, they expected and feared the anti-Syrian backlash. But another thought would occur to them: “Lives of the French people are not more important than the life of a Syrian person,” Shaza says.