Horace Dediu sobered me up. Last year, my initial skepticism of Apple’s rumored car project gave way to more hopeful thoughts. But Dediu’s numbers show how insignificant electric cars still are.

Imagine an Apple electric car that’s as accomplished in its category as the iPhone is in the world of smartphones. Fantasize about the confluence of design, hardware and software attributes, manufacturing technology, and distribution strategy that will make the putative vehicle a perfect object of desire (putative, but less and less so as months go by).

While I’ve tried to maintain an equilibrium about the subject, I haven’t been immune to the virus that has enfevered so many. Looking back over the past year, I see that I’ve written about the Apple Car in no fewer than five Monday Notes musings.

At the outset (“The Fantastic Apple Car“—Feb. 15, “Apple Car: Three More Thoughts“—Feb. 22), I was purely skeptical. Why would Apple enter an industry that has such low margins? Perhaps the car connoisseurs among Apple’s execs had fallen for a classic fallacy: Mistaking their proficiency as customers for the deep knowledge required to be a successful manufacturer. A sophisticated diner does not a restaurateur make.

But then I considered the sophistication and humongous scale of Apple’s manufacturing operations (“Notes From The Road“—March 29). In the December quarter of 2014, just for iPhones, Apple shipped the weight of a Boeing 787—every day. Coincidentally (or not?), that’s about the same tonnage rate as Nissan’s Leaf production in 2014.

A few months later, when I pondered the vast difference between annoying but innocuous personal computer bugs and the (literally) life-and-death demand for reliable software in our cars (“More Apple Car Thoughts: Software Culture“—Nov. 1), I fell back on the doubting side. I didn’t think Apple could adapt its culture to the more stringent requirements.

I ended the year with a more positive outlook (“Money, Design UI, Distribution“—Nov. 30) as I considered Apple’s applicable strengths, and noticed something that had evaded me before: The almost non-existent service requirements for an electric car. Wiper blades once a year, tires even less frequently, engine maintenance…none (I’m oversimplifying a bit). I saw the new Tesla store at the Stanford shopping mall replace Sony, right next to Apple. Sign of the times.

Perhaps my initial fear that the Apple Car was a “It’ll work because it’d be cool if it did” delusion was wrong. Perhaps Apple could shepherd an electric car breakthrough of iPhone proportions… some time after the Cupertino Spaceship lands.

Then I saw Horace Dediu’s blog post titled “Significant Contribution”—and I’m back in “I don’t quite know what to think” territory.

(Monday Note readers know I’m a fan of M. Dediu. Combining tech savvy and business experience, he’s one of our industry’s best analysts. He’s also a keen historian and synthesizer of technologies, giving thought-provoking—poetic at times—presentations of compared trajectories. In addition to his Asymco blog, Horace also produces a series of car-focused Asymcar podcasts and blog posts. A testament to the respect with which he’s regarded, Horace’s posts attract high-quality comments.)

I’ll take the risk of paraphrasing Dediu’s post as a way to drill into what was, for me, an awakening.

The prospect of an electric vehicle triggers pleasant emotions. It’s clean and virtually silent; no tailpipe emissions, no oil on the garage floor. An all around good thing, we need them to succeed. This desire is attested to by the amount of space the topic occupies in the media, in conversations, and in government programs.

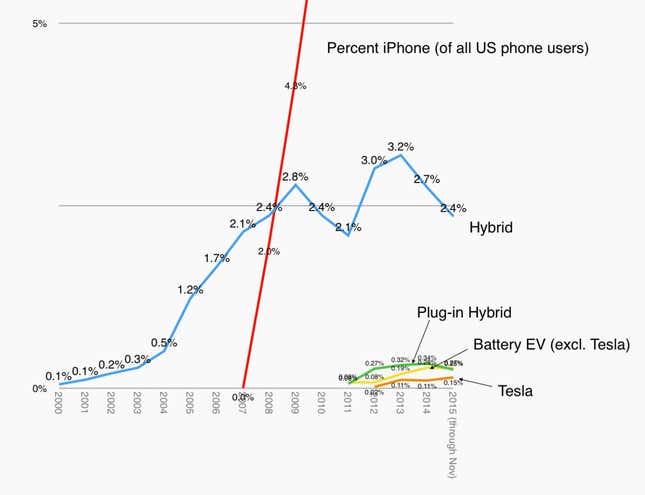

But the numbers send a sobering message. As Dediu’s graph from “Significant Contribution“ shows, we may be talking about electric cars, but we’re not buying them:

Starting in 2000, hybrids did well for a while. The Prius, the most accomplished such vehicle, seems to have done all it could and the category is now in decline, having never achieved more than 3.2% share in the US (these numbers measure vehicles sold, not revenue). Of course, a hybrid isn’t actually an electric car; it’s ultimately powered by a gasoline engine from which some kinetic energy is recovered, stored in a small battery, and returned when most useful.

Purely electric vehicles haven’t fared as well as hybrids. In the eight years since sales were “re-started in earnest” (previous attempts were insignificant), EVs have gained a 0.4% share; Tesla takes 0.15% while losing about $4,000 per vehicle. Contrast this with smartphones [as elsewhere in this note, edits and emphasis mine]:

The iPhone ushered in a new paradigm within the phone market in mid 2007. In the time since, Apple achieved the equivalent of about 35% share of unit sales. [And] significantly more in terms of sales value and over 90% of profitability.

How do we explain the “two orders of magnitude (>100x)” difference between the rapid adoption of the iPhone/smartphone and the electric car’s difficult take-off? What does the e-car’s lumbering trajectory mean for the putative Apple Car?

Simplifying Dediu’s explanation, the iPhone benefited enormously from Moore’s Law, but it also thrived on the self-reinforcing, pre-existing network of customer behaviors, distribution systems, cellular providers, hardware and manufacturing technology… The world was ready for the iPhone.

In contrast, electric cars impose new behaviors upon customers who can no longer abate their “range anxiety” with a three minute fill-up at the corner gas station; charging stations must be built; there’s no Moore’s Law for batteries—their “power” doesn’t double every 18 or 24 months. The “correct” view is that the public should see that EVs are a good thing and bear the growing pains, but the fact is that even after years of “government incentives” (as much as $7,500 per electric car paid to Tesla owners), the market stubbornly resists the good.

Can Apple change this state of affairs?

At the beginning of his post, Dediu cites what he felicitously calls “The Cook Doctrine,” Tim Cook’s stated criteria for Apple to enter a new market:

We believe that we need to own and control the primary technologies behind the products we make, and participate only in markets where we can make a significant contribution.

A significant contribution to the car market isn’t Tesla’s 0.15% share, or even 10 times that number. As Dediu notes:

Making a few cars is easy (see first commandment of The Entrant’s Guide to the Automotive Industry). Making lots of cars is hard and hence significance in the automotive market (as in watches and phones) means achieving some degree of adoption, a higher degree of usage and a very high degree of profitability.

So far, no electric car company has met Dediu’s significance test. More important, none of them show that they can get beyond incremental improvements and percentage fractions any time soon.

What can a car company do to revolutionize the EV market? A possible answer is found, not in the main post, but in Dediu’s reply to a comment:

All meaningful innovation in the automotive industry since its inception has been through the development of production systems. No other source of innovation has caused meaningful change. The industry is completely driven by and controlled and regulated by production systems. The dealer network, the regulatory regime, the rate of change, the modularity level, the approach to technology change, the advertising, the brands, the cross-ownership, the approach to fuels are all derived from the production system.

Counter-intuitive as this might sound, it echoes what I heard at Giugiaro Design years ago. As recounted in “Apple Car: Three More Thoughts,” the legendary Giorgetto Giugiaro insisted that “…his job wasn’t to design an award-winning shape for a car, his job was to design the process, the factory that would eventually excrete a continuous flow of vehicles.”

Thus, the challenge for Apple’s purported car are taller and of a different shape from the ones they faced when creating the iPhone, iPad, and Watch.

First, as Tim Cook states, the company must own and control the primary technologies. That would include batteries, bodies, steering linkages, and their manufacturing technologies.

Second, to make a dent beyond market share percentage fractions, Apple must come up with a truly innovative manufacturing process that creates one of the “sustainable asymmetries” Dediu deems necessary to achieve market significance.

Lastly—even if this gets me another finger-wag from a retired Apple exec—the company’s software culture must experience a secession of sorts. The failure rate of personal computer software is unacceptable in automotive application; a new, separate group culture is required.

If Apple succeeds in overcoming today’s obstacles, the achievement will be even more impressive than the iPhone’s success, and will yet again put the company in a class of its own.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.