Later this month, the FCC will hear a proposal that would put an end to your cable carrier’s costly and regressive monopoly on the set-top boxes that you’re allowed to use. Following their well-known modus operandi, Comcast and other carriers contend that granting this freedom to their customers would stifle innovation. They continue to think we’re idiots, that they can raid our wallets with impunity.

Thanks to the historic Carterfone decision, an FTC edict that forced AT&T to accept third-party devices on its network, you and I can connect any regulatory-compliant device to a telephone line, whether it’s a handset, a fax machine, a DSL modem… Despite AT&T’s noisy objections and dire predictions of technical trouble, sanity prevailed. A customer cannot be barred from “using devices which serve his convenience…provided any such device so used would not endanger the safety of telephone company employees or the public…”

Last week, FCC chairman Tom Wheeler put forth a proposal, to be heard on Feb. 18, that would apply this same logic to cable TV set-top boxes. You and I, says the FCC, should be free to pick and choose our set-top box rather than being forced to rent a device from Comcast or Time Warner.

As expected, the carriers voiced strong objections to chairman Wheeler’s proposal. Comcast immediately issued a blog post penned by Mark Hess, their senior vice president, office of the chief technology officer, business and industry affairs, in which the prolifically titled gent characterizes the FCC proposal as a technological wet blanket:

The proposal, like prior federal government technology mandates, would impose costs on consumers, adversely impact the creation of high-quality content, and chill innovation. It also flies in the face of the rapid changes that are occurring in the marketplace and benefitting consumers…We hope the FCC will decide to avoid this major step backward for consumers and video innovation.

In the post, Hess provides a “we told you so” moment as he reminds us of the failure of the CableCARD. A result of 1996 telecom legislation (an eternity ago in tech space) the CableCARD was meant as a set-top box replacement that could be inserted in TV sets or personal computers. The device failed to gain popularity with consumers. Therefore, contends Hess with unimpeachable logic, this new proposal will also fail.

(We shouldn’t forget the “Freedom Is Slavery“ pablum and the ghostwritten letters of endorsement our highly regarded dezinformatsiya practitioners attempted to foist on us when defending their attempt to buy Time Warner; see earlier words of mine here.)

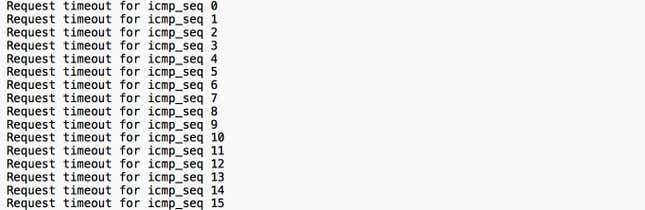

A more credible objection to Wheeler’s proposal is the cable world’s complexity. On the ground, cable systems are a disparate collection, accreted through acquisitions, milked for revenue, but rarely or slowly modernized. In the heart of Silicon Valley, Palo Alto once had its terrible caviar left cable co-op system, sold more than a decade ago to Comcast. Today, in our Palo Alto home, I still experience internet disconnects like this, for minutes at a time (for geeks, output from the Terminal Mac app when pinging Google’s 8.8.8.8 DNS):

Starting a Fargo episode on our Apple TV can take 15 minutes or more. As a result, I took the precaution of securing an additional Internet feed through AT&T. No fiber here, just an ADSL modem and Wi-Fi station.

There are lots of creaky legacy systems out there coexisting with slowly improving mix-mode IP infrastructure in which some cable content comes through a conventional RF signal carried by the coax cable, while at other times/places, the RF signal carries modulated IP packets that encode the video content…

So, yes, it’s messy; Comcast claims that set-top box interlopers who don’t have the carriers’ tech chops would be unable to finesse the twists and turns of the cable bayou.

But is that true?

If we turn our attention to the complicated world of cellular networks, we see that we can walk into an Apple Store, buy an iPhone, and connect it to most of the world’s cell networks. You can move from Verizon to AT&T or France’s Orange merely by swapping the nano-SIM. If Samsung, Lenovo/Moto, and Apple can build multi-carrier phones, who’s to say that Roku, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Apple can’t build a set-top box with a decent UI, integrated Wifi, and an app store full of goods unavailable from cable operators?

Mark Hess and his Orwellian colleagues willfully ignore basic economic facts and seem to hope that we won’t dig too deeply into scare tactics such as the CableCARD monte.

To start with, there’s the outrageous cost of monthly STB rental. As Nilay Patel succinctly puts it in The Verge: “Any rational human being knows that using a cable box sucks—and paying the monthly rental fee sucks even more.”

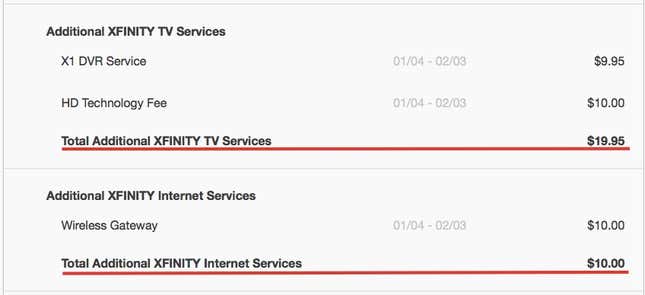

I just checked my Comcast account:

The Comcast TV + internet connection box costs $359.40 a year, which is probably close to the manufacturing cost. And I love the “HD Technology Fee” because, you know, it costs a lot to add HD rendering to a DVR that comes out of the factory with HD built in. Nice work if you can get it.

(As an aside, we actually have two Comcast accounts, one for Palo Alto and another for San Francisco. Irritatingly, the company won’t let me use the same account for the two locations—they insist on two account numbers, two logins, two bills, even as they accept the same credit card on autopay.)

What do we get for our money? As this Open Technology Institute cost of connectivity study documents, we pay more but we get less for broadband [as always, edits and emphasis mine]:

[…] the data that we have collected in the past three years demonstrates that the majority of U.S. cities surveyed lag behind their international peers, paying more money for slower Internet access.

Then, Hess would have us believe that Comcast’s monopoly on set-top boxes fosters innovation. As if competition between Google, Apple, Amazon, Roku, Microsoft—maybe even Facebook and other entrants—wouldn’t yield more interesting and less expensive devices.

As I’ve written several times, (here as an example, you can Google “Monday Note set top box” for more), carriers are the wrong suppliers for set-top boxes, they have the wrong incentives, the wrong skills, and the wrong culture. The future, as we already see but cannot yet reach, is TV-as-apps, on any screen. The Super Bowl? An app, free because of the ads. Fargo is an app; ad-free (if you pay) or watch-for-free (but with ads). The cable carriers’ mission is exactly the opposite: They need to preserve an increasingly obsolescent money pump that bundles channels and hardware.

I’m not a complete naïf. The solons that We the People elect so they can sell themselves (and us) to lobbies have allowed market-distorting combinations, like Comcast absorbing TV company NBC. I also realize that the interlocked agreements between content producers and distributors look like intractable obstacles to the unbundling steps we hope for.

Still, with a grateful thought for Steve Jobs, imagine an alternate universe in which AT&T and Verizon’s vCast controls mobile content distribution. There would be no App Stores from Apple and Google, no explosive growth of Smartphone 2.0.

We look at a cable operator as the adversary in a sort of cold war, a supplier we have to use but can’t trust. The American Customer Satisfaction Index puts cable carriers at the bottom of their scale:

Americans dislike cable companies more than any other industry in the nation—and that loathing is often laser-focused on some of the biggest names in the business.

Contrast this with the general feeling towards businesses such as Amazon and Apple. Their customers, myself included, are quick to criticize when performance fails to meet expectations, but distrust and loathing aren’t the standard mode of relating.

Chairman Wheeler’s proposal, if adopted after the usual convulsions, astroturf campaigns, and hearings, might not completely change our current pathological state of affairs, but it’s an important step in the right direction. I hope consumers and media won’t let incumbents snuff out the initiative with money and disinformation.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.