Google’s master plan for mobile is finally coming into focus.

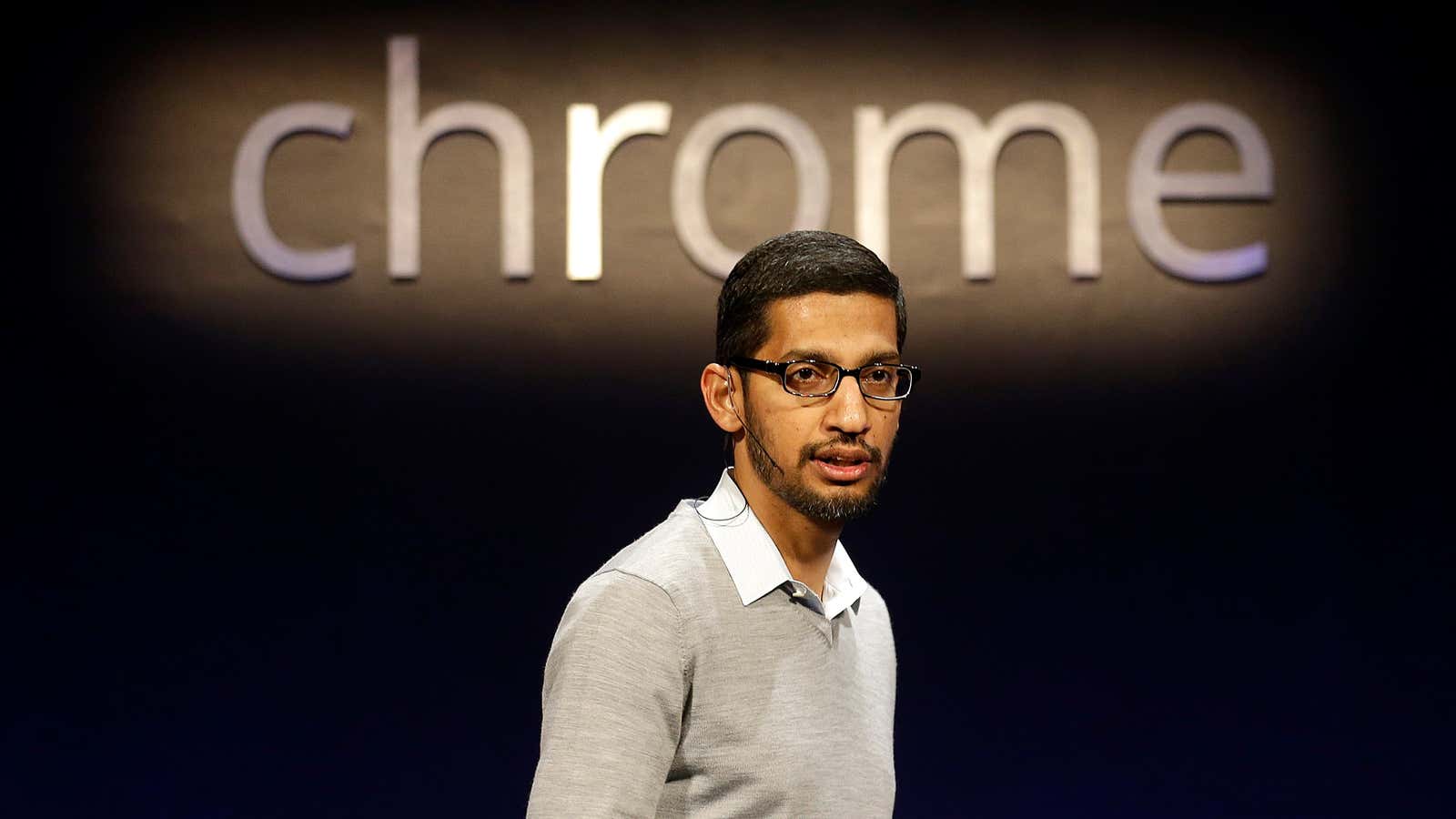

The latest development: Andy Rubin, who has run the Android mobile operating system since 2004, even before it was acquired by Google, is stepping down. Taking over Android will be Sundar Pichai, currently the head of Google’s Chrome web browser and Chrome OS project. And here’s where Google shows its hand: Even as he takes on new responsibility for Google’s mobile strategy, Pichai will remain in charge of Chrome.

Somewhere in the afterlife, Steve Jobs just yelled, “Boom!”

Google is preparing for hybrid, mobile PCs

The distinction between PCs and mobile devices is blurrier than ever, and Google seems to be setting itself up for the moment when Android (for mobile devices) and Chrome (for PCs) become one.

In 2011, Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt said that Android and Chrome OS would some day fuse. Android currently runs the majority of smartphones in the world, while Chrome OS is Google’s successful but still nascent attempt to provide people with an alternative to Windows on their notebook and desktop PCs. Putting a single person in charge of both Android and Chrome at once is rather transparently the fastest way to get both projects headed toward some kind of union.

Schmidt has also said that Chrome OS is for devices with keyboards, and Android is for devices without. But as the world fills with all manner of hybrid beasts—tablets with keyboards, laptops that convert to tablets, smartphones that become tablets, gigantic smartphones and even notebooks designed to run Windows and Android simultaneously—it’s apparent that these distinctions are, if not exactly meaningless, then at least increasingly unhelpful. People are having fun with and getting work done on whatever device is at hand. Call them mobile PCs.

This explains Google’s Chromebook Pixel

Google recently released the Chromebook Pixel, a high-powered laptop that only runs its own Chrome OS. The operating system is good, but it isn’t nearly as capable as Windows or Mac OS X, and its primary talent right now is a great web browsing experience and native integration with Google’s cloud services like Gmail and Drive. In other words, it’s great for cheap laptops, but Chrome OS simply isn’t doing anything taxing enough to warrant all the horsepower and expense of the Chromebook Pixel. Reviewers savaged it accordingly.

But now we see where Google is going with all of this. Like the operating system that runs on Apple’s iPhones and iPads, one of the strengths of Android is its enormous library of “native” apps—that is, applications that you download to the device before using. Native applications can do things web-based applications still can’t, like intensive video editing and high-end gaming.

Once Google fuses Android and Chrome OS, Chrome will get the huge library of native applications that it currently lacks, and Android could gain the desktop-like features that make Chrome so useful for getting real work done. Some of these advantages are quite simple: Chrome has true “windowing,” which means that the web applications running on it can be run in individual windows instead of browser tabs or, as is common in mobile operating systems, as full-screen apps.

But how will Google avoid the Windows 8 trap?

If all this sounds familiar, it’s because the exact same vision animated Microsoft Windows 8, which puts a mobile and tablet-friendly interface alongside regular old Windows. But most people have found that fusion leads to unacceptable compromise.

Here’s the key difference for Google, if Chrome and Android merge: Google does not have to support a huge population of existing users of its desktop operating system. Chrome OS is only four years old, and it wasn’t until recently that cheap laptops pre-loaded with Chrome OS made it the least bit mainstream.

Microsoft’s strength is also its weakness: Millions of businesses have built applications on top of Windows that Microsoft must support with each successive version of Windows. Google’s primarily obligation, on the other hand, is to the hundreds of millions of people who already use Android, a lightweight, stable, constantly improving operating system that is already close to being capable of allowing users to do “real” work with it.

Unburdened by the need for backwards compatibility and empowered by all the lessons tallied so far by the PC industry, Google has the chance to create an operating system that spans all devices and is truly workable—not just a kludge like Windows 8.

Android + Chrome OS is a money maker

Currently, Google doesn’t charge a licensing fee to the companies, like Samsung, that make billions of dollars selling mobile devices that run Android. Google’s only way to make money directly from Android is through the Google Play store, where it sells apps, and so far the Play store is not a material portion of Google’s income. (Of course, Google-approved versions of Android keep people using Google’s services, where the company can place advertising.)

But a fused Android and Chrome OS opens up a number of new potential revenue sources for Google. Foremost among them is simply charging for future Google services. While Gmail might always be free, Google is happy to charge users to store their data. As people move more and more of their lives to the cloud, Google could potentially lock them into life-long subscriptions to its data storage and other services.

Google is already accomplishing this at the enterprise level with the per-user subscriptions to a suite of Google apps.

Let the age of cloud-based personal computing begin

Google’s move to fuse Chrome OS and Android is perfectly in line with its identity as an internet company. Chrome OS epitomizes Google’s view that no matter what device you pick up, simply logging in should present you with the same experience, no matter what. Google recognizes that what users want isn’t control but fluidity.

People want that moment in the movie Avatar, when a character swipes a document from a flat panel monitor onto his tablet computer, so he can carry it around with him as he walks. We live in an age in which, Google Docs and iCloud and Microsoft Office 365 notwithstanding, the dominant method for sharing data between computers, even computers owned by a single person, is still email. What we could have, instead, is a single unified digital life that is abstracted into the cloud. In this world, every device, no matter its size or capabilities, is simply a window into our online workspace. A world in which all screens are created equal.

Google is trying to realize this vision, but so far its expression—force users into a Chrome OS in which everything is run through the browser—has felt limited. But these are the early days, and the company’s larger ambitions have yet to be realized. The only question is, will it be called Chandroid or Androme?