The future of Twitter, according to CEO Jack Dorsey, is live—as in right now.

Dorsey, who is tasked with turning around Twitter, told investors earlier this month the company was focusing on what “Twitter does best”—and a key part of his strategy hinges on Periscope, the live streaming app it acquired last January.

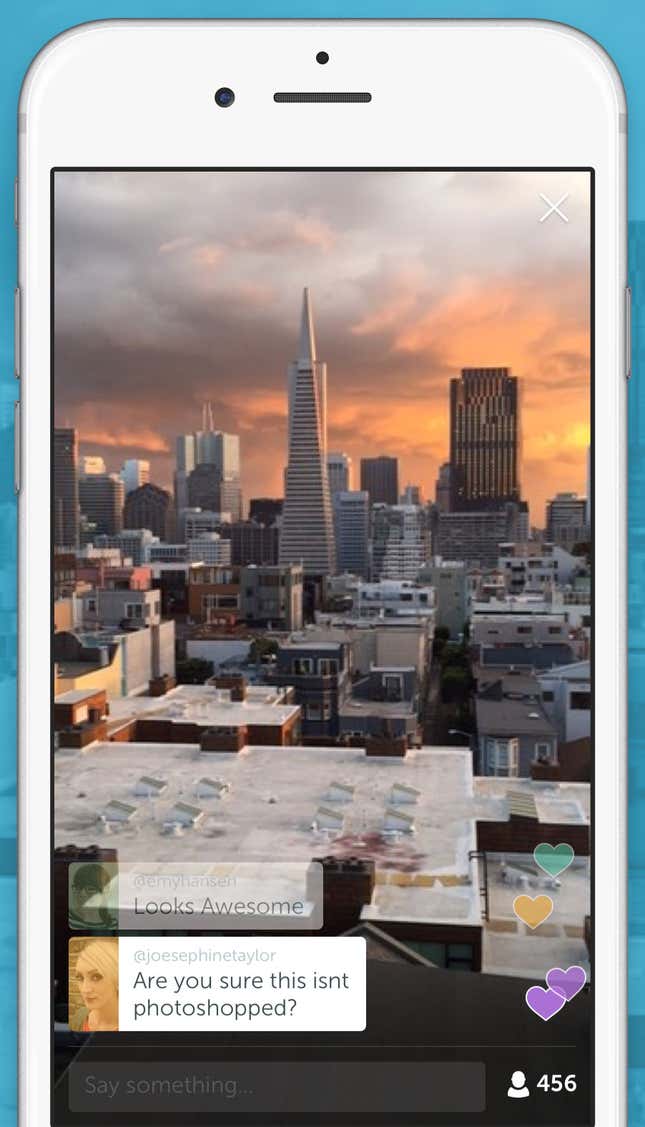

Periscope and rival live streaming service Meerkat were considered the breakout apps of 2015. Though live streaming is not a new concept, these apps made it simple for people to broadcast directly from their smartphones.

“The core vision is just to see anywhere in the world right now,” Tyler Hansen, Periscope’s lead designer, tells Quartz. In the early days, the team thought that meant viewing people’s pictures from around the world, with some gamification elements, like earning points, thrown in. Hansen, who joined when the company was only two people, says that eventually the startup realized “well, video’s better than photo.”

Hansen sat down with Quartz to talk about the evolution of Periscope’s design, the painstaking labor behind its fluttering hearts, and how his grandparents have been ”hugely influential” beta users.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

In January, you guys finally integrated Periscope into Twitter. What needed to happen before users could view Periscope streams directly from the timeline?

We wanted to give exactly the right feature that people really wanted, and that worked the way they wanted.

Another good example of this is our community was constantly asking for fast forward and rewind on replays, which we didn’t have and that was something we built right away. Internally we had fast forward and rewind, but it wasn’t really good. So we took some extra time to design a new custom scrubbing interface that allows you to skip any point in a broadcast, and it’s very well suited for mobile.

How has the design of Periscope evolved over time?

I think [switching from the] square video with comments that stayed forever … to full screen and the comments that faded away was without a doubt the most impactful change we made.

We went through and built a lot of features we ended up removing—just built them, tried them, and it didn’t work. Some notable ones are stuff like scheduled broadcasts. That’s actually something our community asks for today continually. We had it in beta, we built it, and we learned a lot from it. And we learned enough to make us remove it.

People could subscribe to it and get a notification in the future, but only a small percentage of those people actually ended up tuning in, which led to disappointment for the broadcaster.

Are the hearts (which viewers send to broadcasters by tapping on their screens) a gamification element that you carried over from the early version of Periscope?

A little bit, yeah. … I mean people can totally see the similarities between the hearts and maybe coins popping out of a box in Mario.

I, from a design perspective, try to use a lot of cues from video games because they’ve been sort of dealing with these live presence issues a lot longer than we have. Multiplayer online video games have been about bringing people from all around the world to one place at the same time, even though it’s a digital place. When it comes to live video, same things apply.

What went into the design of the reaction hearts?

Originally, they just popped in and went straight up, but it was still something that faded away over time. But we knew we wanted a little more. I was taking the time to learn a little bit of iOS coding myself, some Swift, and so I took the opportunity to write the algorithms myself because these sorts of animations are hard to do in design software.

Every heart is completely unique. All the pathing that they do is random so they’re all very different which gives them a human flair. There are lots of little details. They also rotate just a little bit—well not of them.

They have an energy to them that is different depending on how many there are. When only one person is tapping once in a while, they actually only go up about halfway through the screen or something. They’re a little bit slower. But every heart comes on the screen for three seconds at a time.

The more hearts there are, the faster the hearts move vertically and you get this very interesting energy.

How do hearts encourage people to broadcast?

Early on when we were building, it was always scary even though it was only to broadcast to our friends, you know? It was like getting on stage and in front of unknown amount of people with very little feedback.

If you are actually on stage, you can read the audience and how well they like things. That’s when we started thinking of things like hearts—again ephemeral time-based feedback that was very simple to do for a viewer so that the broadcaster knew you were there. All you had to do was tap on your screen and the broadcaster saw you were tapping on your screen. Knowing someone was there helped a lot.

I hear you don’t like emoji.

That gets around. I’m not a fan of emoji abuse. It’s like curse words. If you use it too much they lose their power.

But aren’t hearts emoji?

I get criticism for that too. “You’re the biggest fan of emojis because of hearts.” That’s valid. I don’t know what else to say. Yep, they are.

You mentioned at the recent Periscope Summit in San Francisco that only 8% of broadcasts are private. Is that a number you guys are trying to increase?

Private broadcasts is a great example of a feature we built in beta that we weren’t sure about. Like everything else, some [features] got kicked out but this stayed around. We think there are a lot of cool use cases of family and close friends. For example, my wife does a private broadcast to me and my grandparents and my parents and [other family members] of my daughter at the park.

Wait, your grandparents are on Periscope?

Oh yeah, they were very early beta users—and hugely influential ones—because they’re not good at technology. I basically had to teach them to use an iPhone at the same time as Periscope. They just got it. That was very important to me because they don’t get Facebook. They don’t get Snapchat. But when my grandpa saw the live video and saw you could send messages to the person and they’d respond—just immediately he understood.

My grandpa uses it probably at least as much as I do. They started getting up there in age so they can’t get around as much. We’ve heard from a lot of people in similar situations that Periscope lets them get around and that just touches us in unimaginable ways.

What are the metrics you care about?

We’re generally not very metrics driven. Part of that is because we had no metrics in beta, at least not statistically relevant metrics, so we started making much more decisions based on how we felt.

You’ve said that in five years you envision the app fading back. What do you mean by that?

I want people to be so comfortable with this new medium that it can sort of be a way for people to get together and communicate and talk. And it’s like getting together. It’s not broadcasting or watching. It’s just being in the same place at the same time.

I know this is super corny, and I hate it when [CEO and cofounder] Kayvon [Beykpour] says it, but it’s teleporting. That’s what I mean. Just letting all the barriers of technology fading away and letting it be about the human connection between people. That’s a goal everyday and in every feature we do.

So how much do you broadcast?

I like to on occasion, particularly about designs. I’ve had a really fun time broadcasting older versions of Periscope, pointing the phone at my screen saying, “It used to be like this. This is why we’re doing this now,” and I think everybody gets a lot of value out of that.

That’s mostly what I Periscope about, is Periscope. Because I don’t have that much else interesting in my life other than private broadcasts and my family and my kid. Hopefully I’ll find myself in an extraordinary situation and I can do something that’s not about Periscope.