“You must trust and believe in people or life becomes impossible.” Russian playwright Anton Chekov might have been right that we can’t go it alone, but we’re also right to be skeptical of others.

The great skills required of a con artist, politician, or salesperson are also the skills of great creatives: The ability to manipulate reality (in Spanish, the root of “manipulate,” mano, means hands; so to manipulate is to “handle or control in a skilled manner”), direct (and misdirect) attention, mimic, tell compelling stories, etc.

Picasso told us that “Art is a lie that tells the truth.” Writer Ursula Le Guin admitted that “A novelist’s business is lying.” And Marlon Brando said, “If you can lie, you can act.”

The job of a good storyteller, marketer, or writer is to pull one over on you. To make you believe what they’re saying, no matter how farfetched it might be. And just like Mulder, we want to believe. As author and artist Hugh MacLeod sums up so perfectly:

Whether you’re writing a post, negotiating a deal, or designing a site, understanding how we are influenced will always pay off. So how do we learn to harness the power of persuasion? Through looking at the people who persuade you to do things you never thought you would.

Here’s how some of the world’s greatest (yet maybe not the most savory) persuaders—from con artists to politicians—use your emotions to get you to do what they want.

Salespeople

Let’s start with the most widely accepted group in the persuader posse: salespeople. By definition, their job is to separate you from your hard-earned cash. Peter Drucker famously wrote that the aim of marketing is to make selling superfluous: “The aim of marketing is to know and understand customers so well that the product or service fits them and sells itself.”

And yes, persuading someone who’s already interested in what you’re selling to actually buy it merely comes down to highlighting the ways it will benefit them. But where’s the fun in that? A good salesperson can sell a venison steak to a vegan. How? Well, that’s where the fun comes in. Research has shown that up to 95% of the decisions we make happen subconsciously—giving a huge amount of room for anyone with persuasive tendencies to guide our choices without us even realizing.

As Robert Cialdini, author of Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, expresses: “People’s ability to understand the factors that affect their behavior is surprisingly poor.” We might not know why we do the things we do but a good salesperson can read the subtle subconscious signs you’re giving off and play you right into their web.

Here’s a look at some of the best techniques good salespeople use to get you to say yes, even when you don’t know why.

1.Take a ride down the Persuasion Slide

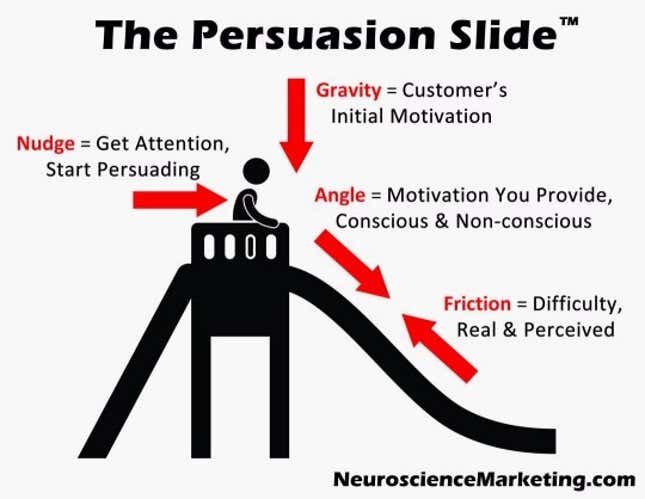

On his Neuroscience Marketing blog, Roger Dooley describes what he calls the Persuasion Slide.

We all have some level of internal motivation, which any good persuader works to exploit. In Dooley’s slide model, this is gravity. The level of motivation you already have determines how persuasive you’ll have to be:

Without a steep enough angle, slides don’t work. If this motivation isn’t strong enough, the customer will begin to slide and then stop. I break this into two types of motivation: conscious and non-conscious.

Conscious motivators are what most marketers focus on: features, benefits, price, discounts. But these are all things that apply to the rational part of your brain—which, as we saw, makes a mere 5% of your decisions. That’s not what we’re after.

Now, non-conscious motivators are what can sway the hardliners. This is where you move the decision from a rational one to an emotional one, bypassing the logical mind by focusing on things like:

- Reciprocity: Making your customer feel like they “owe you one.” We’ve been socially conditioned to return favors, which is why free samples or an unexpected “upgrade” almost always works to make us spend more. Just look at the free buffet at a Vegas casino to understand this technique.

- Scarcity: Make your customer feel like they only have one chance to get the product. We’re more likely to bypass any logical arguments if we think we won’t get another chance to buy.

- Using ultimate terms: In every language, there are certain words that carry more cultural weight. On the Changing Mind blog they break these words down into three categories: God terms (blessings that demand obedience), Devil terms (evoke disgust), and Charismatic terms (more intangible, but still powerful).

God words usually evoke some emotional or basic need like safety or belonging. Here’s a list of words often used by salespeople to demand obedience:

- Safety: guarantee, proven

- Control: powerful, strong

- Understanding: because, as, so, truth, real

- Greed: money, cash, save, win, free, more

- Health: safe, healthy, well

- Belonging: belong, happy, good, well

- Esteem: exclusive, only, admired

- Identity: you, (their name), we

- Novelty: new, discover

However, we have to remember that while these are “ultimate” terms, where a word falls on the scale can change over time as its cultural associations change. Just look at the words that set off your email’s spam filter: “Act now!” ”Free.” “Affordable.” “Cheap.” “Limited time offer.” These spam words were all once God terms, but their overuse pushed them off their top position.

2. Get them to say no

All the sales training in the world might push you to get clients or customers to say yes more often, but studies have shown that this repetition can dilute the significance and confidence of each yes. Putting your prospect in a position where they say no (and subconsciously feel more in control), means they’ll be more inclined to stick with their response when they do actually say yes. You can consciously script your pitch or sales funnel to let your customer start off by saying no to easy questions so they’re more likely to agree later on when it matters the most.

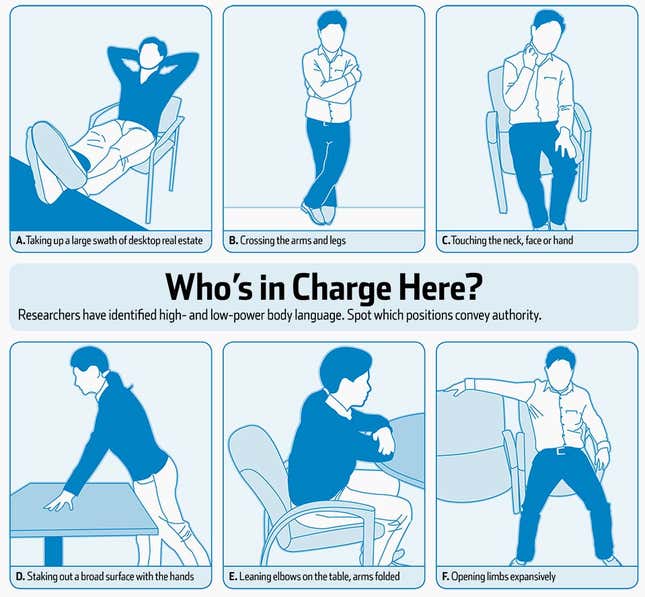

3. Put yourself in a position of power, literally

There’s lots of studies out there showing how body language can influence negotiations, but it’s the transition from weak to powerful that really helps in sales. The best salespeople start the conversation slightly lower (both metaphorically and literally) than their customer.

But as the sale moves forward, they slightly rise until they’re in a dominant position. The gradual transition subliminally stages the customer to be more receptive to suggestions from the salesperson.

How con artists con

A recent New York Times article highlighted the plight of 33-year old Niall Rice, a consultant in Manhattan, who little by little gave $718,000 to two psychics who promised to reunite him with an old flame. “I just got sucked in,” he said. “That’s what people don’t understand.”

There’s a thin line between good salesperson and con artist, yet the biggest difference is not only in why a con artist persuades you to do what they want, but in how.

The long con—the big influence—depends on following one golden rule: Know your mark.

In her book The Confidence Game, psychologist Maria Konnikova spoke with con artists and their victims to understand how they worked, and why their techniques worked. What she found was that, like with a hard sale, it all comes down to making it emotional.

Step 1:

Know who you’re talking to. Know where they’re confident, but more importantly, where they aren’t.

Step 2:

Look for the cracks. Being in an emotionally vulnerable situation opens you up to persuasion (like the consultant missing his ex). When your life stops making sense, you’re more than willing to listen to someone who is giving you answers you like.

Step 3:

Create a cult of trust. The psychics in Niall’s story used mysticism to convince him to keep paying them. Their services were ones of faith, not reason. If you can, don’t go up against widely held belief systems. Instead, use your knowledge to create your own systems of belief. Ferdinand Waldo Demara, also known as “The Great Imposter,” masqueraded as a surgeon (performing actual surgeries), a lawyer, prison warden, cancer researcher, and Benedictine monk. He called this “expanding the power vacuum”:

That way there’s no competition, no past standards to measure you by. How can anyone tell you aren’t running a top outfit? And then there’s no past laws or rules or precedents to hold you down or limit you. Make your own rules and interpretations.

Persuasion and influence is easier in spaces where you can become an authority—places without clear rules in place. As an “expert,” you’re more likely to be trusted.

But, as Paul J. Zak, a neuroeconomist at Claremont Graduate University explains, the key to a con is not just that you trust the con artist, but that they show trust in you (remember the salesperson’s use of reciprocity?):

Social interactions, especially ones where we feel in a superior position like when helping another person, engage a powerful brain circuit that releases the neurochemical oxytocin, which induces a desire to reciprocate the trust we have been shown—even with strangers.

Oxytocin’s effects are modulated by our large prefrontal cortex that houses the ‘executive’ regions of the brain. Oxytocin is all emotion, while the prefrontal cortex is deliberative.

So even if we believe we’re acting rationally, being shown trust and vulnerability from another person physically forces us to think emotionally—the key to all persuasion.

Politicians

At the top of our persuasion pyramid is the politician.

While a con artist may persuade one or two people to go along with their story, politicians face millions of opponents, each with their unique worldview and emotions. So how do you go about persuading such huge groups of people to follow along with your ideas?

When it comes down to it, a vote for a politician is a vote for a way of life. Your choice is informed by your belief of what issues really matter and what you find morally correct.

In their study, “From Gulf to Bridge: When do Moral Arguments Facilitate Political Influence,” researchers Robb Willer and Matthew Feinberg found that not only are our political choices controlled by moral judgements, but that we experience those moral convictions as factual and universally applicable.

Once we believe in certain values, it’s incredibly hard to persuade us to think otherwise. Wildly different beliefs can be perceived as the right belief without any sort of logical reasoning taking place. And when we try to understand values other than our own, we hit a moral empathy gap—an inability to look at the issue from a standpoint other than our own.

Where most politicians and would-be influencers fail, is in not understanding just how ingrained these moral convictions are. There’s no way to simply argue rationally about the merits of say, same-sex marriage or increased military spending, to someone who strongly disagrees with either of those on an emotional level. So here we hit the wall. Here is the unpersuadable issue. Right? Not entirely.

There’s a technique called moral reframing, whereby you reframe your argument to align with the values of your audience. Focus on what they value. Not what you do.

In an article called “Mapping the Moral Domain” published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, professor Jesse Graham surveyed thousands of people around the globe and found that our moral foundations can be placed in one of five categories:

- Harm/Care

- Fairness/Reciprocity

- Ingroup/Loyalty

- Authority/Respect

- Purity/Sanctity

Looking at US politics as a pretty clear example of hard-lined moral convictions, Graham and other researchers found that liberals are most concerned with issues of care and fairness, while conservatives care most about loyalty, respect, and purity.

So how does a good influencer use this knowledge to persuade the opposition? As Don Draper would say: “If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation.” In Willer and Feinberg’s study, they presented liberals and conservatives with one of two messages in favor of same-sex marriage.

The first emphasized the need for equal rights for same-sex couples (targeting those more attached to moral values of fairness), while the second argued that “same-sex couples are proud and patriotic Americans,” who “contribute to the American economy and society.”

Liberals showed the same support for same-sex marriage no matter what statement they were shown (because they already believed in same-sex marriage and didn’t need persuading). But conservatives supported same-sex marriage significantly more if they read the patriotism message rather than the fairness one.

In another study, Feinberg and Willer found that conservatives demonstrated greater support for pro-environmental legislation when advocacy statements were framed in terms of purity rather than in terms of the more liberal values of harm or a control. In both cases, nothing different is being said, but the way the statement is framed changes everything. As professor Willers sums up in an article from The New York Times:

You have to get into the heads of the people you’d like to persuade, think about what they care about and make arguments that embrace their principles. If you can do that, it will show that you view those with whom you disagree not as enemies, but as people whose values are worth your consideration.

The principles of persuasion

So what can we take away from the techniques of these unscrupulous characters?

1. Know who you’re up against

What Konnikova calls “the put-up,” the first stage of the con—or, persuading argument—is all about research and identifying just who it is you’re looking to influence. Market research, customer outreach, data tracking—these are all ways to get an idea of who it is you’re up against.

2. Understand their pain and show them benefits

For the con artist, this is the scheme or tale you tell, where you allow the subject to come to the conclusion you want them to—without too heavy of a guiding hand. For the rest of us, this means using the research you’ve done to provide a clear answer to your customer’s pain.

3. Grease the slide

Once the persuasion is going full-steam-ahead, there’s nothing to do but step back and stoke the fire as needed. Grease is best used sparingly, so a bit of scarcity—and a dash of social proof—is probably all you need to keep things moving.

4. When the going gets tough, the tough get emotional

And when you come up against objections or push back? Get emotional. As we saw from pretty much every major con or mass persuasion, we’re all just emotional creatures who are more than happy to justify our decisions with “logic” later on.

5. Change the conversation

Flip the script. If what you’re saying isn’t working, use your empathy to understand how your mark is thinking and reframe the argument using their values. The most important thing to note about any con artist, grifter, salesperson, or politician is that they only succeed because we let them.

The only time a con will really work is when it preys on some aspect of life that you want to happen. The motivation is already there, somewhere inside of you. And no matter how small the spark, with enough work someone can stoke it into a roaring fire. We want to believe, and a good influencer just pushes us in the right direction. But don’t just run out and start using these dark arts of manipulation for evil. As Robert Cialdini warns:

When these tools are used unethically as weapons of influence … any short-term gains will almost invariably be followed by long-term losses.

Crew publishes regular articles on creativity, productivity, and the future of work. Enter your email here to get their weekly newsletter. You can also follow Crew on Twitter and Facebook.