For anyone trying to reduce their impact on the environment, the task can be daunting. It’s difficult for businesses in particular, and maybe especially so for a fashion brand. It takes a lot of water, energy, and often pesticides to grow the materials for fabric, while the chemicals used to dye and finish them can result in nightmarish water pollution in countries such as India and China. Then, all those clothes that are sold are eventually discarded, and often wind up in landfills.

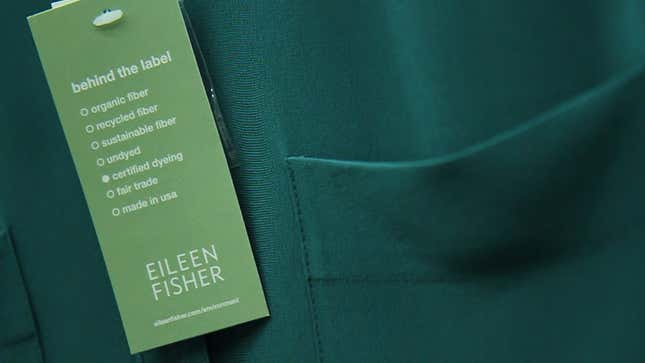

There’s no clear roadmap for addressing these problems, and it’s complicated enough that even a label such as Eileen Fisher, a noted industry leader in sustainability, doesn’t have it all figured out.

On Eileen Fisher’s site right now, there’s an image of one of the loose-fitting, minimalist linen tunics that has made the brand the epitome of understated, mature elegance. But, the caption declares, ”This is not a perfect picture,” since only 52% of the linen in the garment is organic. “That’s going to change.”

The company, which did $444 million in sales in 2015 and has about 1,200 employees, is learning as it goes, bumping up against what it doesn’t know. And there’s an important lesson, for other businesses and shoppers alike, in Eileen Fisher’s acknowledgement of its occasional ignorance: It shows you don’t have to be perfect to start having a real impact.

Nobody’s perfect

At a luncheon the company held late last year, Fisher herself admitted that her team is constantly discovering things they didn’t know. She had just found out that a lot of wool is treated with chlorine (pdf). It’s part of a process to make it machine washable, but leads to toxins ending up in wastewater.

In 2014, the company had made a similar discovery regarding viscose (pdf), which is a regenerated cellulose fiber made from wood pulp and requires a toxic solvent to produce. It was extremely problematic, says Amy Hall, its director of social consciousness, because viscose is one of their biggest sellers.

“We have a huge financial investment in this fabric. It’s a customer favorite,” she says. “We decided that we need to completely eliminate it from our portfolio, and we set a goal of 2020 as our deadline without having any idea how we were going to replace it.”

The company is still figuring it out. Right now, it looks like Tencel, a more sustainable wood-pulp based fabric, will make up the bulk of the replacement. Between 2014 and 2015, the company more than doubled its use, while viscose went from 90% of fabrics made from regenerated cellulose down to 77%. It’s a long way from the target, but it’s meaningful progress.

Meanwhile, 92% of Eileen Fisher’s cotton is organic, as is 83% of its linen. The goal is to use 100% organic fibers for each by 2020. Hall says the company will hit those marks well ahead of schedule.

A company-wide priority

One of the big barriers a company runs into when trying to change how it works is that goals aren’t always shared by all its departments. Many brands have separate sustainability teams that may set goals, but their objectives aren’t fully integrated with those of, say, the design and production departments.

Eileen Fisher has gotten where it is on sustainability by making these goals a priority throughout the organization. About three years ago, when Eileen Fisher began focusing specifically on reducing its impact, it started from a core group of dozen or so decision makers across different parts of the company. Slowly but steadily it has brought more people into the discussion, through in-person workshops and a presentation available at all times online, and now it’s just part of how the company operates.

“It’s really being held equally by our leader of design, our leader of manufacture and product development, our leader of brand communications, our co-creative officers, and many others,” Hall says. “Because of that, the work is really embedded in all of their teams, and there are multiple working groups that emanate out from all of these individuals.”

It starts with asking questions

To focus a business on sustainability is an ongoing challenge, but getting started is simple. It’s just about asking questions.

Many fashion brands don’t actually know the backstories of their materials. A recent report (pdf) on the Australian fashion industry, for instance, found that 75% of brands didn’t know the histories of all their fabrics and other inputs, while 91% didn’t know where all their cotton comes from.

But Fisher has been looking for that information since a trip to see her company’s supply chain in person put her face-to-face with the water pollution in China. ”Now we’re starting to ask, ‘What goes into that? What do you actually use in the processing of that fiber, or the finishing of that fabric?'” Hall says.

There was an element of fear involved in digging deeper, especially when it was unclear how the company would address problems, but it decided to forge ahead. A year ago, the brand launched Vision 2020, a comprehensive plan to improve the environmental and social effects of the business.

“For many years, even though we’ve been kind of heading into this space slowly and methodically, there’s always been a huge element of uncertainty that accompanies this,” says Hall. “What we decided with this new rebirth around sustainability is that we’re embracing what we don’t know.”

Eileen Fisher can never reach total perfection when it comes to eliminating its environmental footprint. Raw materials, stores, transport, and all the other aspects of a modern business have an impact. But that isn’t exactly the goal, according to Hall. Instead, Eileen Fisher wants to inspire others in the fashion industry to reconsider how they do business, and to ask how they can go from what she calls a “model of doing less bad” to one that’s genuinely restorative.

It won’t be easy, but it starts with asking the question.