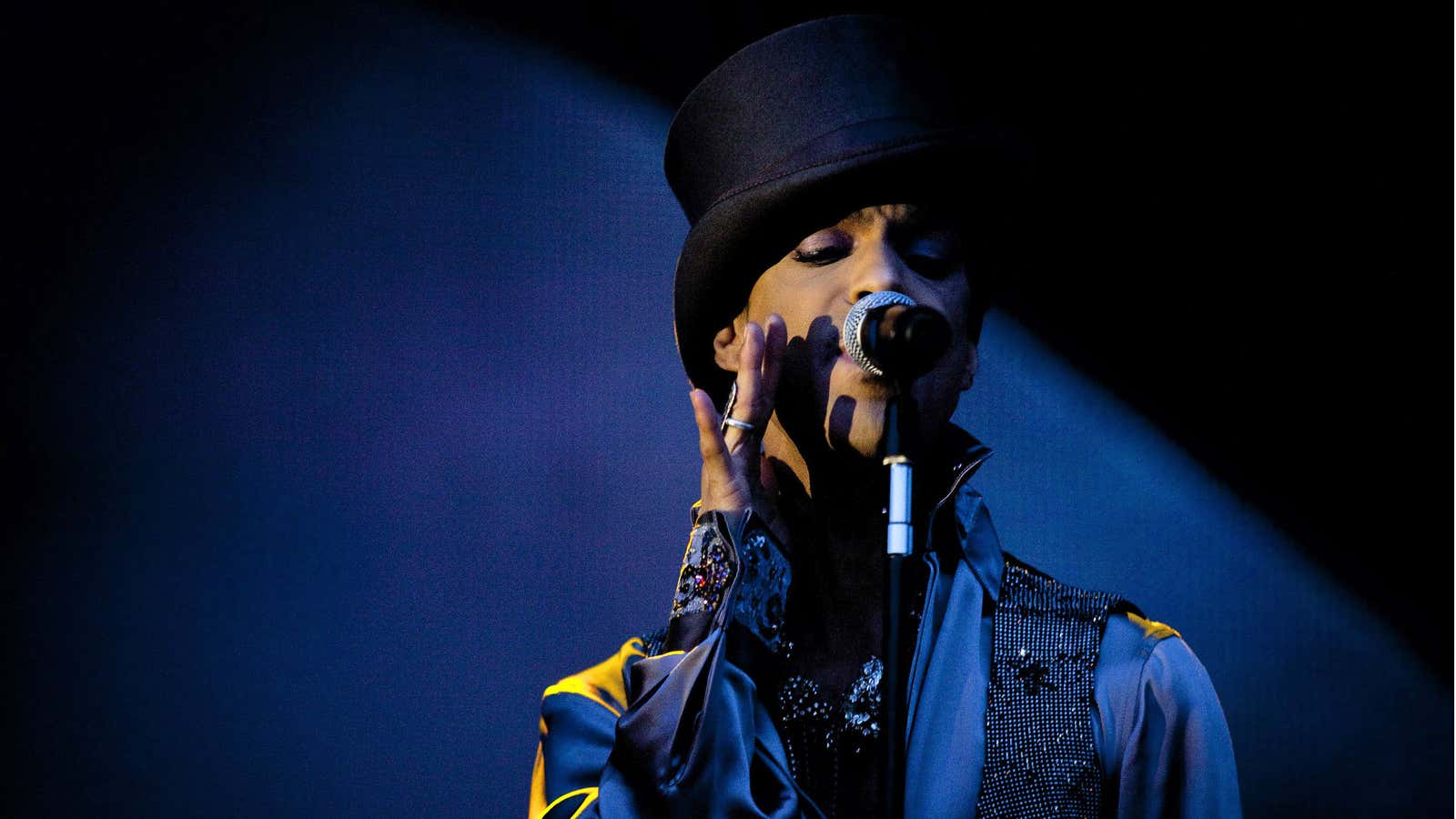

Prince was actively seeking the help of opioid addiction specialists in the days leading up to his death, according to the Minneapolis Star Tribune. The morning his body was found, on April 21, he was scheduled to meet with Andrew Kornfeld, a staff member from Recovery Without Walls, a rehabilitation facility in California, according to a lawyer representing Kornfeld.

Toxicology results are still pending, but if Prince did indeed die from an opioid overdose, he will be just one of thousands of Americans who have fallen victim to prescription painkillers. Since 1999, the number of opioid-related deaths have nearly quadrupled.

The above data include all the reported causes of death in which prescription opioid painkillers, like Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet were involved. Technically, individuals could have died from other causes as well.

Opioids—whether prescription painkillers or heroin—reduce the perception of pain and create feelings of pleasure. They are highly addictive: Over time, the body’s opioid receptors become accustomed to the drug; users may need to take a higher dose to get the same euphoric feelings and stave off withdrawal. When taken in excess, opioids can kill users by depressing their ability to breathe.

In March, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released guidelines about how doctors can help curb the opioid crisis. One of the most obvious measures was to reduce the amount prescribed to avoid future problems with abuse and addiction. In 2012, American doctors wrote out 259 million prescriptions for opioid painkillers. They are prescribed so widely that a single year’s total is enough to dose the entire US population around the clock for a month.

And as the Boston Globe reports, the United States is dealing with two inter-related drug abuse epidemics: One for prescription pills, and one for heroin.

Taken together, they are a significant factor in “deaths of despair,” which also include suicide and liver failure due to alcohol consumption, which have taken a noticeable toll on life expectancy for the white working class.

“Increases in deaths of despair have been large enough to outweigh the progress made in reducing mortality rates from cancer and heart disease, the two biggest killers of middle-aged people,” wrote Princeton economist Anne Case, who has led research into the trend. Quartz’s Allison Schrager noted that the opioid epidemic has also disproportionately affected women.

Black Americans have been less susceptible to prescription painkiller epidemic—ironically because many doctors are “much more reluctant to prescribe painkillers to minority patients, worrying that they might sell them or become addicted,” one drug abuse expert told the New York Times. “Racial stereotypes are protecting these patients from the addiction epidemic.”