“Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”

Tomorrow (June 23), voters in Britain will answer this seemingly simple question.

The question has become heavily loaded over months of bitter campaigning. The official campaign groups, Vote Leave and Britain Stronger in Europe, have forcefully presented their visions for the country in or out of the EU, making many claims about the economy, health system, security, workers’ rights, sovereignty, immigration, and much else besides.

Voters, meanwhile, appear evenly split. After such a divisive, angry campaign, the rhetorical devices that ultimately prove more persuasive may set the tone for elections, and politics in general, for years to come.

Take control

Vote Leave has relied heavily on emotion. Its core message was an appeal to ”take back control” from unaccountable bureaucrats in Brussels. The EU’s immigration system is “out of control,” it noted. Nigel Farage, leader of the far-right UK Independence Party, said a vote for Britain to exit the EU (“Brexit”) on June 23 would mark the UK’s ”independence day.”

The parallels with populist statements made across the Atlantic by bombastic presidential candidate Donald Trump—making the country great again, asserting sovereignty, rallying against the establishment—were not lost on observers. (For his part, Trump thinks the UK would be “better off” by leaving the EU.)

“There’s definitely an attempt to create a romantic idea of what Britain could be like out of the EU,” says Andrew Crines, a lecturer in British politics at the University of Liverpool. The EU is cast as “a distant, malevolent force that tells us how to behave, and once Britain is free we can thrive again.”

This approach has a long history. In a 2015 study analyzing the evolution of British discourse about Europe (pdf) over the past 40 years, John Todd from the University of Oslo highlighted “a consistent divide between a British self and continental other,” which was reinforced by “increasing prominence of anti-immigration rhetoric.”

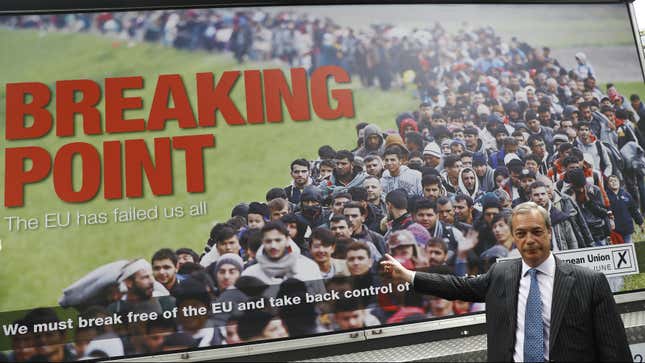

Criticism of the “leave” campaign’s anti-immigrant leanings reached its zenith last week, when Farage unveiled an anti-EU poster depicting a line of mostly Middle Eastern migrants and refugees which was likened to Nazi propaganda. Soon after, Sayeeda Warsi, former chair of the Conservative Party, quit the Vote Leave campaign, citing messages that stirred ”hate and xenophobia.”

Fear and loathing

Divided though both sides have been, their statements share a common theme: fear.

The “politics of fear,” according to Ruth Wodak, a professor of linguistics at Lancaster University, are “very strong in persuading audiences who don’t have much information to vote with their gut feeling, which is where rational discussions don’t find a space.”

Vote Leave’s populist brand of fear has largely centered on the encroaching powers of the EU if Britain were to stay in the bloc, namely around the loss of sovereignty and control of immigration. (Citizens of EU countries are free to live and work in any other member state.)

The “remain” campaign, meanwhile, has been routinely criticized for “scaremongering.” Its message has focused on the uncertainty and instability that could result from disrupting the status quo, warning against “an insecure future where catastophes would happen, and insinuating to the past of world wars, complete insecurity, and fragmentation,” Wodak says.

The economic arguments are overwhelmingly in favor of “remain” (paywall). Philip Corr, a psychology professor at City University, London, points out how the “remain” side has shrewdly personalized the economic risks of leaving. “‘Your future’, ‘your risk’ and so on—this is a very effective means to convey a message,” he says.

Corr also points to the power of loss aversion: that is, our tendency to prefer avoiding losses than seeking gains. Or, in the professor’s words: ”Why risk losing what you have?”

Nuance-free zone

What the soaring rhetoric sometimes—often, even—fails to answer the one thing voters want to know: how Brexit would impact them on a practical, day-to-day level. ”People aren’t bothered by abstract notions of sovereignty. They want to know if they’ll have a job, a house, and can feed themselves,” says Crines of the University of Liverpool.

“It’s a difficult, nuanced issue characterized by both sides as a binary decision of great ‘in’ or great ‘out,'” he adds. This comes back to the politics of fear employed by both sides, adds Wodak of Lancaster University. “Where there is polarization there is either/or, and the either/or on both sides both have such threat scenarios,” she says.

Consequently, there is ”no space for really debating the pros and cons or what reforms could look like,” she says. Neither of the official campaign groups responded to Quartz’s request for comment.

A tragic crescendo

Suddenly, the toxicity of the debate was put into sharp relief following the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox in the street in her Yorkshire constituency last week. When Thomas Mair, the man charged with her murder, was asked to give his name in court, he replied: “My name is death to traitors. Freedom for Britain.”

Both Conservative prime minister David Cameron and Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn called the murder “an attack on our democracy.” Cox campaigned for refugees’ rights and was a staunch supporter of the UK remaining in the EU. As her husband, Brendan, put it: “she had very strong political views and I believe she was killed because of those views.”

Shocked, and also perhaps chastened, the campaigns immediately suspended their operations. With a jolt of sudden, grief-laden perspective, the mood of the debate shifted; the divisive war of words seemed unseemly in the circumstances. As Brendan Cox told the BBC:

I think she was very worried that the language was coarsening, that people were being driven to take more extreme positions, that people didn’t work with each other as individuals and on issues; it was all much too tribal and unthinking.

In the final stages of a somewhat more muted campaign, statements have been “examined through the window of this tragedy,” Crines notes. ”I think the tragedy will force us to look at ourselves and the kind of democracy we have become.”