Line’s $1.3 billion IPO shows cuteness is the new killer app

The largest tech IPO of the year takes place this week, as Japanese chat app Line sells $1.3 billion worth of shares on the New York Stock Exchange today (July 14) and the Tokyo Stock Exchange on Friday.

The largest tech IPO of the year takes place this week, as Japanese chat app Line sells $1.3 billion worth of shares on the New York Stock Exchange today (July 14) and the Tokyo Stock Exchange on Friday.

Despite the eye-popping valuation, there are plenty of reasons to be bearish about Line’s long-term growth prospects. The company’s chat app is only popular in a few Asian countries and is not growing its user base. Its experiments outside of messaging and gaming have been failures. Facebook Messenger, an app which itself is inspired in part by Line, could steal customers. And app makers worldwide are struggling to get users to download new apps.

Luckily, Line has a crutch. A bevy of cuddly characters may turn it into a licensing behemoth, and perhaps help launch new hit apps as well.

Increasingly, app makers are realizing that the best way to ensure an app gets attention is to rely on familiar faces and franchises. There’s no better example of this than the success of Pokemon Go. The Nintendo-backed title soared to the top of the app charts largely on the heels of nostalgia for beloved characters like Pikachu. Another example is Glu Mobile, which enjoyed success when its app Kim Kardashian: Hollywood became the top-downloaded game in the US. The game was remarkable only for its titular character, but helped bring in $100 million in 18 months.

Line is just as adept at marketing its cute characters as it is at messaging.

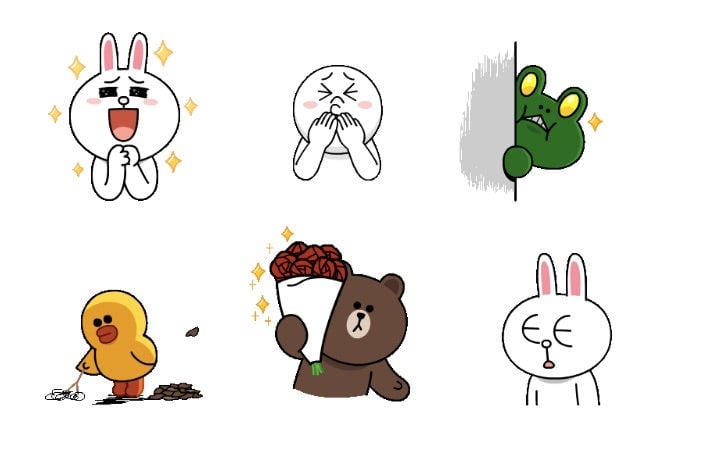

Line is famous in Asia for introducing some of the most beloved cartoon characters the continent has ever seen, including Cony (a bunny), Moon (known for his big head), Leonard (a frog), Sally (a duck), and Brown (a bear).

These characters are featured prominently in Line’s enormous catalog of “stickers,” which are like giant emoji that users can obtain for pocket change and use again and again. And they bring in a large amount of money for Line.

Stickers like the ones below, which cost $1.99 for a set of about a dozen, helped the company generated $268 million in revenue in 2015, or about 23% of its total revenue.

Line’s characters don’t just live inside screens throughout Asia. They’ve have penetrated the cultural zeitgeist. Throughout Taiwan, Japan, and Southeast Asia, Line’s characters appear on T-shirts, plush toys, key chains, SIM cards, coffee mugs, snacks, and countless other merchandise.

Like Hello Kitty, Brown and Cony don’t really “do” anything. There’s no memorable origin story or narrative that people associate them with. They’re a cartoon equivalent of “famous for being famous.”

Even in China, where Line’s chat app is blocked, consumers will line up to grab branded goodies at the company’s pop-up stores.

Line merchandise isn’t limited to the company’s own retail outlets. It can be found in ordinary convenience stores too. In Hong Kong, one block from Quartz’s local office, you can purchase packs of toilet paper featuring Sally and Moon.

What’s most startling is how Line’s characters have endured since 2011, apparently getting more popular all the time.

Offline, Line could market its characters to any business that wants to use them. Restaurants, theme parks, apparel companies, and entertainment studios may hand Line money in exchange for the rights to use Cony and Brown on merchandise and media. This is how Sanrio, creator of Hello Kitty, makes money. In 2015, the company made $656 million in revenue, with much of that coming from licensing deals.

Online, Line’s instantly recognizable characters help ensure that its new apps get noticed—and downloaded. The company enjoyed modest success with two game titles bearing its mascots. Data from App Annie shows that Line Rangers, an adventure game, held steady as one of the top 100 most-downloaded games in Japan and Taiwan throughout 2014, and Line Pop, a Candy Crush-esque puzzler, did the same in 2013.

It’s possible the company could enjoy even more success if it follows the route Nintendo took with Pokemon Go and licenses out the characters to a skilled game maker, splitting the money that comes in.

At the moment, licensing makes up a small but growing portion of Line’s revenue. On its prospectus (p. 77), the company classifies its merchandise licensing business as part of an “Other” category that grew from 1.7% of Line’s total revenue in 2013 to 5% in 2015.

“Line Advertising,” which includes licensing its characters to businesses to make branded sticker sets (for example, Cony holding a Big Mac) grew from 13.4% of Line’s total revenues to 22% throughout the same period. Tellingly, these are the only segments of Line’s income that are growing.

As competition from Facebook intensifies and the well of new messaging users dries up, Line will have to find new ways to make money and keep growing. Investors should keep their eyes on the bears and the rabbits.