Amid the recent storms over police shootings and deaths, we should be focusing on America’s unequal education system instead of only concentrating on police-community relations.

Police chief David Brown understood this when he addressed the media after a lone sniper targeted and killed five Dallas police officers. He questioned why cities have turned their police forces into the Mr. Fixit for economically devastated communities: “Not enough mental-health funding? Let the cops handle it. Not enough drug-addiction funding? Let’s give it to the cops.” At the memorial service for the five slain officers, president Barack Obama also echoed this sentiment: “We ask police to do too much, and we ask too little of ourselves.”

Obama was not just responding to the slaughter in Texas, but also to the deaths of two black men—Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Philando Castile in a suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota—at the hands of the police. These instances sparked a wave of nationwide protests that eventually put the Dallas police department in the crosshairs of a sniper. Just over a week later, another three officers were killed in yet another retribution attack in Baton Rouge.

In this moment of crisis and grief, both chief Brown and president Obama tried to tell a story with a much broader perspective than that of the actual killings: They recognized the untenable situation for the police, who have to deal with the consequences of shredded safety nets.

“The police are a flash point,” says Marc Morial, the president of the National Urban League (paywall). “The broader situation is always the underlying issues: the criminal justice system being broken, the higher unemployment among African Americans, the slower recovery from the recession, and the assault on voting rights and voter suppression.”

And what do these issues all have in common? They spring from the unequal education America offers its children.

Education can be transformative. It reshapes our health. It breaks the cycle of poverty. It improves housing conditions. It raises the standard of living. Perhaps, most meaningfully, educational attainment significantly increases voter participation. Education strengthens a democracy, and unfortunately for too many in American society, that was a threat.

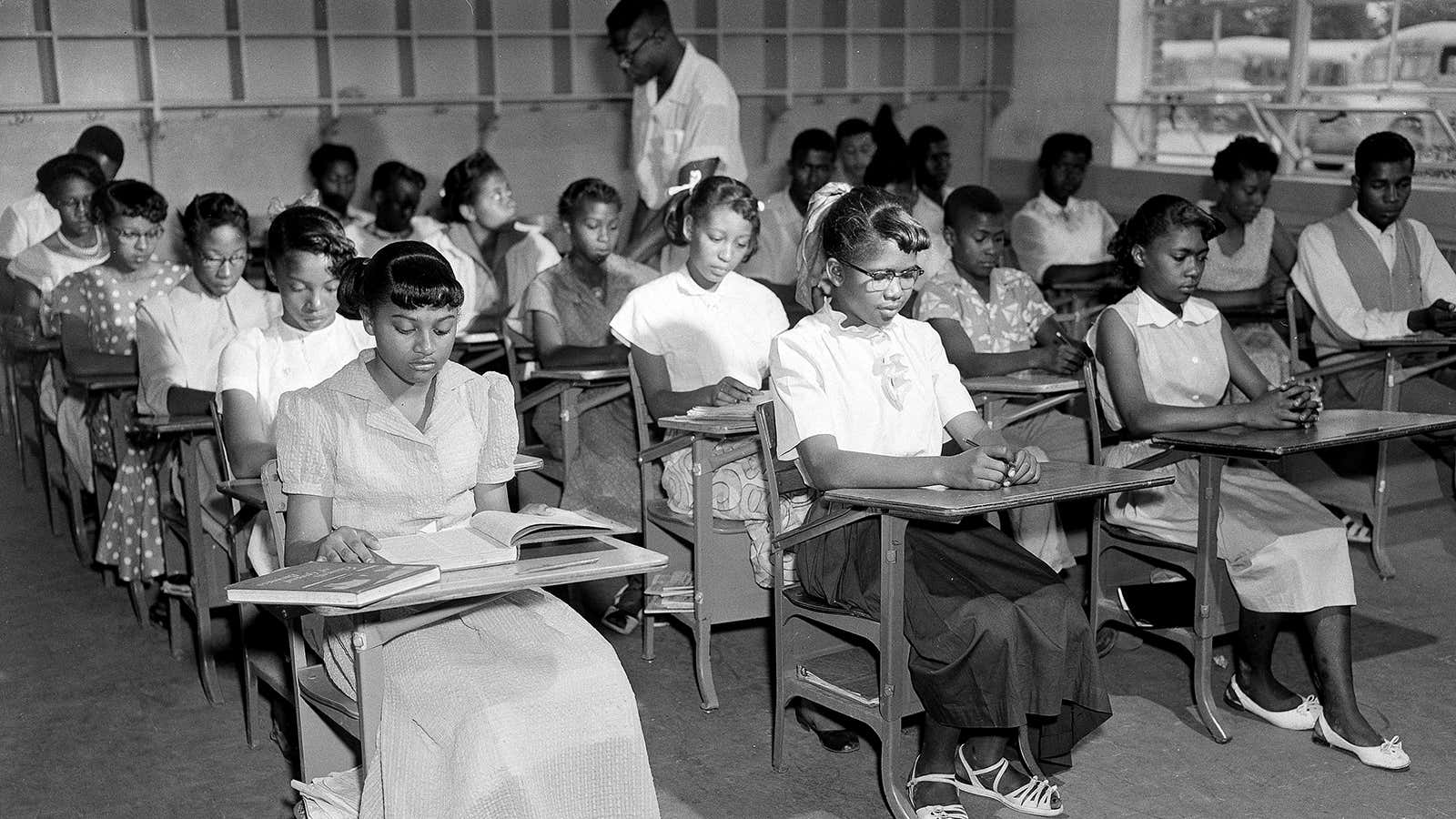

Since the days of enslavement, African Americans have fought to gain access to quality schools. In 1954 when the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that separate and unequal was unconstitutional, the Southern states dug in. They saw this as the next round of the Civil War and devised a range of legislative weapons to undercut the decision. They trampled on the First Amendment by banning the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People from operating in their states. They created the legal fiction of interposition that gave states the authority to block federal law. They even closed public schools, funneled tax dollars into tuition payments for white children to attend all-white private academies, and left black children with no viable educational alternatives at all.

As a result, millions of African Americans who were determined to get a quality education instead faced shuttered schools or blatantly unequal educational institutions. This situation occurred despite a landmark Supreme Court ruling and the onset, not too many years later, of the American economy’s transformation from one that was dominated by manufacturing to one based overwhelmingly on technology and knowledge production. In this way, America in the 1950s should be seen as a fateful time when history failed to turn and alter the trajectory of the nation.

The Brown ruling initially held out hope. Children clamored to go to school—fought for it, even. Black adults also put their lives on the line for the children. Reverend Joseph DeLaine sued Clarendon County, South Carolina for gross unequal education and became one of the cases bundled in Brown. In doing so, he faced the unbridled wrath of local whites. As Richard Kluger writes in Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality, “They fired him . . . they fired his wife and two of his sisters and a niece… And they sued him on trumped-up charges and convicted him in a kangaroo court and left him with a judgment that denied him credit from any bank. And they burned his house to the ground while the fire department stood around watching the flames consume the night.”

As governors, state legislatures, congressmen, US senators, and even local courts defied the law, the legitimacy of American democracy was on the line. Few who were battling Brown seemed to care.

For example, when the US Supreme Court forced the schools to reopen in Little Rock, the most liberal member of the school board proposed using the law to undercut Brown and limit how integrated Little Rock schools would be. Using the same factors that Mississippi had considered—“ability,” “whether a good fit or not”—he argued that pupil-assignment plans could ensure that most African Americans stayed right where they were in their “well-segregated neighborhoods.”

Meanwhile, a handful of blacks could be enrolled in white schools—just enough, he explained, to “satisfy the federal courts,” but at the same time, “small enough to satisfy the reluctant and vocal whites in the community.” This tactical shift from stall and defy to stall and undermine effectively clogged court dockets for more than 40 years. African Americans struggled to nail down a moving target whose goal had not changed: Stop black advancement.

African Americans weren’t the only ones who took a hit. All of the delays, foot-dragging, and obstruction forestalled creating strong, viable schools across the nation, even while the clock was ticking on American global economic competitiveness. The states of the deep South, which fought Brown tooth and nail, today mainly fall in the bottom quartile of state rankings for educational attainment, per capita income, and quality of health.

In particular, Virginia’s Prince Edward County bears the scars of a place that saw fit to fight the Civil War right into the middle of the 20th century. It is certainly no accident that in 2013, despite a knowledge-based, technology-driven global economy, the number one occupation in the county seat of Farmville was “cook and food preparation worker.”

Nor is it any accident that in 2013, 32.9% of black households made less than $10,000 in annual income, while 9.9% of white households fell under that threshold. The insistence on destroying Brown, and thus the viability of America’s schools and the quality of education children receive regardless of where they live, has resulted in what former US secretary of education Arne Duncan called “the economic equivalent of a permanent national recession” for wide swaths of the American public.

So when it comes to reform, we are asking police to do too much, for we are asking them to take on the consequences of previous policymakers’ refusals to treat black children as citizens worthy of quality schools. In turn, this asks the African-American community to shoulder the consequences of a historical moment when history failed to turn.

Adapted from White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide by Carol Anderson. Copyright © Carol Anderson 2016. Published by Bloomsbury USA. Reprinted with permission.