The strangely bifurcated legal status of marijuana in the United States didn’t get any more sensible yesterday, when the Drug Enforcement Administration responded to a petition to remove the drug from its place as one of the most pernicious controlled substances in the US with a polite “no.”

The decision not to move marijuana to a less-restrictive category or take it off the controlled substances list altogether came with a one concession to cannabis advocates: The DEA will allow an end to the monopoly held on marijuana grown for research, all of which previously came from a single facility at the University of Mississippi. They plan to contract with at least one new supplier.

The limited amount and quality of marijuana available for research has been regularly cited as a key barrier by scientists in establishing once and for all that it is less dangerous than drugs like heroin, cocaine, and even alcohol.

But because marijuana remains a controlled substance, experts say expanding marijuana research will still take years to accomplish. Schedule one substances can only be studied in specially designated labs by licensed researchers, and today, there are only 350 people certified in the whole country. Any new production facilities will require the same extensive security systems and procedures.

“I don’t think the ending the [research marijuana production] monopoly increases the number of studies,” says John Hudak, a political scientist who tracks drug policy at the Brookings Institution. “I think it increases the quality of studies and that might be important. It might help move along how the medical community accepts medical cannabis.”

Several private companies investing in marijuana research told Quartz they plan to keep their focus overseas.

“We need to take a close look at what opportunities have become available,” says Patrick Moen, a former DEA agent who is now general counsel at Privateer Holdings, a fund that invests in cannabis business. ”It’s fairly straightforward to do that research overseas…it will be undoubtedly more burdensome to do it here, even after today.”

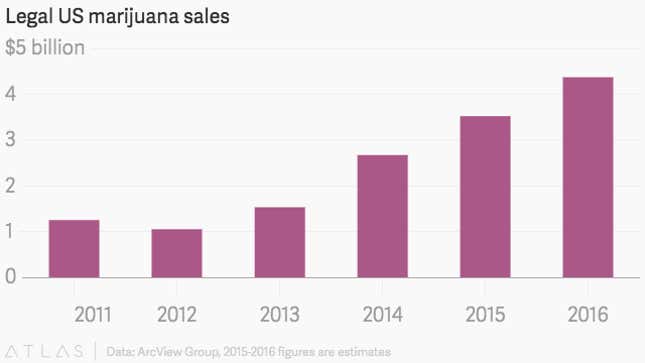

Several states now host burgeoning legal markets for marijuana, and several more, including California, where medical marijuana is already legal, are expected to follow suit this fall. Many see national legalization as inevitable at this point.

But the federal government still isn’t ready to move. Despite the massive change in public opinion on marijuana legalization in recent year, it’s rarely anyone’s top issue and support is particularly low among older Americans—and law enforcement officers.

Many cannabis fans were disappointed by the decision. “Mind-boggling…intellectually dishonest and completely indefensible,” said the Marijuana Policy Project’s spokesperson. The decision “flies in the face of objective science and overwhelming public opinion,” said the executive director of the National Cannabis Industry Association.

Advocates for marijuana and criminal justice reform feel that they were led on by Obama, who in 2015 said that “we should follow the science as opposed to ideology” when it comes to marijuana. But it became clear that the administration was not willing to spend political capital on downgrading or removing marijuana from the controlled substances registry. In January of this year, a White House spokesperson said Obama was waiting for Congress to take the lead: ”Why don’t you pass legislation about it and we’ll see what happens?”

But advocates say that when confronted with a Congress unwillingness to take action on other issues—such as fighting terrorism or helping immigrants—Obama hasn’t hesitated to use (and some say abuse) his executive powers to act. Meanwhile, he’s proved unwilling to take on his own DEA.

Any disappointment in the decision is tempered by the high likelihood that changing marijuana’s place on the controlled substance list is merely the first step toward expanding research and creating a path for the FDA to approve cannabis medicines. It wouldn’t affect the state-level cannabis markets springing up around the US or access by medical marijuana patients. And anyway, the burgeoning cannabis industry operating in states where marijuana is legal is far more interested in federal legislation that would allow their businesses to use banks.

For many, it’s just plain stupid that the federal government’s official policy on marijuana is that it “has a high potential for abuse…and no currently accepted medical treatment use in the U.S.,” but that local jurisdictions are free to develop their own legal medical and recreational markets to sell it.

“When I left the agency,” says Moen, the former DEA agent, “I would say without a doubt, senior management was out of touch. I think it’s improved. Trying to change institutional culture like that is trying to turn a cruise liner; at this point I’ll take anything I can get…the announcement today is progress.”