When we have trouble making sense of what a company says about its business, it’s a sure sign of trouble.

“Without clear explanation there can be no successful execution.”

In this simple sentence at the end of a recent Monday Note, I was attempting to explain that the clarity of a company’s “What we do here” statement (Verizon’s, in this case) is a strong predictor of the company’s future success. But given the questions from a handful of readers, I see that I wasn’t clear, and thus failed in the execution. Specifically, I forgot to follow my own “For example” rule: Lofty general statements must be brought down to Earth by an example or two.

Today, I do penance.

A first example comes from a (barely apocryphal) conversation in an engineer’s cubicle decades ago. Newly parachuted in his organization, I listened as he animatedly described his work. I asked: “Why are you doing this?”

A blank stare.

I say nothing and wait. A tentative “Because I’m told to…” comes out.

“No that won’t do. You have this reputation for being independently-minded. Try again. And don’t say you’re working on a request from Marketing. Everyone around here knows what you think of them Playtex and Pepsi types.”

A thin smile replaces the blank stare.

“Look. This is a business, not a coding resort. If you can’t say why you’re doing what you’re doing, you’re possibly dangerous. You need to articulate why your work will make our product work better, cost less, sell more, attract new customers…”

As it turned out, the test was on me.

The gent belonged to the Brains and Arses school of organizations. (When you look down, you see brains. When the brains look up they see…).

The brainy engineer wanted to know what the arse at the top had in mind.

We quickly came up with a two-word motto fit for my license plate and t-shirts. Dissenters self-selected themselves away, and the organization coalesced around a clear goal.

Ideally, a company motto is short, resonant, and memorizable. This makes it resistant to confusion and agitation. Whether you’re the receptionist, the independent-minded engineer, or the top arse, you must always be able to recite it. Even at 3am. Even if you’re tired, drunk, and distraught. Even if your spouse just threw you out on the street in the rain in your underwear.

I exaggerate, of course. But only a little, as the following counterexample will make “clear”:

Our vision is to create technology that makes life better for everyone, everywhere—every person, every organization, and every community around the globe. This motivates us—inspires us—to do what we do. To make what we make. To invent, and to reinvent. To engineer experiences that amaze. We won’t stop pushing ahead, because you won’t stop pushing ahead. You’re reinventing how you work. How you play. How you live. With our technology, you’ll reinvent your world.

Seventy-seven words…to say what? How does this pablum tell an engineer, a salesperson, or an accountant what the company is about, what it does, why, and how?

I found this “vision statement” on HP’s website. It concludes with another dose of pretentious vagueness:

“This is our calling. This is a new HP. Keep reinventing.”

The “new HP” part refers to Hewlett-Packard’s long-awaited split into two entities. We now have the “new old HP” with its traditional PC-and-printer business, and the split-off HP Enterprise that sells hardware, software, and services to businesses.

For the “new old HP” how about this:

“We make PCs and printers. For individuals and businesses.”

If you want to add a dose of (hopeful) exceptionalism, you might add something like:

“That best integrate into your work and life environments.”

The “What we do here” statement over on the HP Enterprise side isn’t much better:

“We Are In the Acceleration Business. We help customers use technology to slash the time it takes to turn ideas into value. In turn, they transform industries, markets and lives.”

One would be forgiven to think that this is the statement for IBM, the ur-Enterprise computing solutions company. (Perhaps a merger of the two similarly-motto’d entities is somewhere down the road? But I digress.)

One could question the professional future of the marketing person or communications consultant who came up with the shamefully trite “Our vision is to create technology that makes life better for everyone, everywhere” or the confusing “they [meaning the ideas?] transform industries, markets and lives,” but that would be unfair. The responsibility for defining an organization’s raison d’être, its identity, belongs to the CEO—the person everyone in the company looks up to.

We get the impression that the company chief is afraid to admit that the “new old HP” (kicked to the curb, actually) is in a declining commodity business, and that he’s unwilling to embrace his company’s place in the race to the bottom. This isn’t the best way to align energies.

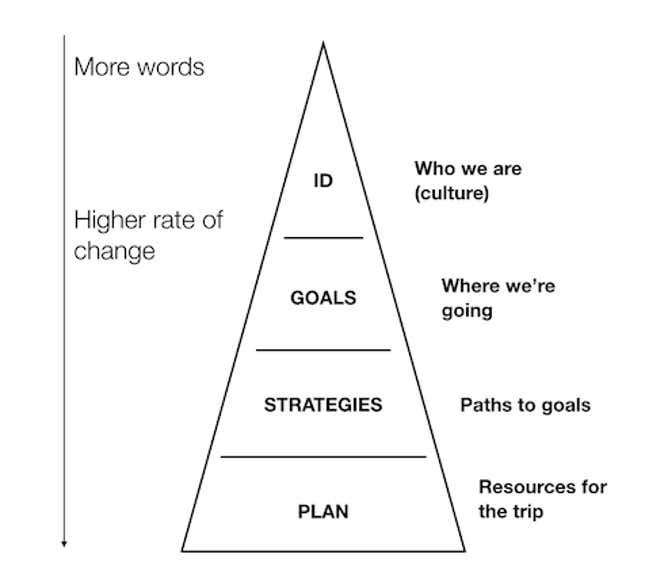

One useful BS detector—including one’s own—is the following diagram:

For example, too many words to describe the organization’s goals spell trouble. An eight page mission statement I once saw tells everyone the organization has SOE (Strategy Of Everything) trouble—the leader doesn’t know what to do, and “focuses” on everything, just in case. This is the road to mediocrity, paved with Powerpoint slides, Excel sheets, and Gartner quadrants.

The identity layer can’t change, if ever—it is deeply seated in the minds, hearts, and guts of the organization. Consider how IBM always was, and still is, the Enterprise Solutions company. The operating plan, on the other hand, is voluminous with details—and changes all the time as circumstances, competition, and crises dictate.

Too many words—changing too often at the wrong layer—tell us the story is poorly thought-out and, most important, is likely to lead the organization astray.

For better examples—for clear, resonant raison d’êtres—we can turn to successful companies.

Google, for example, has a set of clear statements, such as “What we do: Our products and services“:

Google also features another page titled “Ten things we know to be true“ [only a small portion pictured below]:

There’s more, such as “Our culture.” All well-worded and even felicitous in places, such as #2, above: It’s best to do one thing really, really well.

Relevant and rightfully ambitious as they are, Google’s “What we do” and “Ten things” are too complicated to be easily recited at 3am in the rain. And because you know we’re not too keen to show what’s behind the fig leaf, they sidestep the company’s real mission: “We use our superior search engine to gather user data to sell targeted ads.”

What this simple statement makes explicit is the company’s life or death activity. Indeed, as Google financials show, advertising revenue is everything—actually more than 100%, as other activities in the Alphabet soup do not make real money. With this firmly established, everything else can be characterized as either a supporting character or a distraction (or, sometimes, a very long-term bet).

One easy criticism of such a simple statement is that it is too simple—it lacks nuance. To which I’d reply that we don’t need to introduce complexity. Reality will do it by itself.

Amazon

Amazon is similarly loquacious about its purpose on its richly-documented About Amazon website. But Amazon also offers a short, eminently memorizable mission statement:

“Amazon is guided by four principles: customer obsession rather than competitor focus, passion for invention, commitment to operational excellence, and long-term thinking.”

Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos makes a point of reprinting the statement in his annual letter to shareholders (a very good read).

While Amazon’s statement is an improvement over HP’s, its inspirational attitude feels almost unnecessary in a company that has an unwavering, 22-year legacy of strong leadership. Also, the one-liner fails to evoke Amazon’s emerging profit machine: Amazon Web Services.

A less aspirational, more down-to-Earth statement might read:

“We are the world’s 360° e-commerce company. We run a free cash-flow machine to finance our growth.”

Facebook also benefits from strong, respected leadership. It’s certainly one of the best-led companies in the tech world, one where everyone knows “What we do here”:

As with Google, the “What we do here” omits the advertising money pump, and could be rephrased thus:

“Our social network connects people. In doing so, we collect personal data that allow us to sell targeted ads.”

The unspoken implication: Everything else that we do is in support of the main activity.

Apple

We now turn to Cupertino [from recent PR material]:

Apple revolutionized personal technology with the introduction of the Macintosh in 1984. Today, Apple leads the world in innovation with iPhone, iPad, Mac, Apple Watch, and Apple TV. Apple’s four software platforms—iOS, macOS, watchOS, and tvOS—provide seamless experiences across all Apple devices and empower people with breakthrough services including the App Store, Apple Music, Apple Pay, and iCloud. Apple’s 100,000 employees are dedicated to making the best products on earth, and to leaving the world better than we found it.

Long as it might be (82 words), it’s clear, relevant, complete, and devoid of bland generalities. One might quibble that claims of “making the best products on earth” breaks the third party rule: Don’t go around saying how good you are in the sack, leave that to your happy partners.

A shorter statement would be easier to memorize and still capture Apple’s essence:

“We make personal computers—small, medium, and large. Everything else—software, services, and other hardware—only exist to propel their volumes and margins.”

This simple statement leaves room for growth: The company’s culture may mature, but its fundamental nature doesn’t change. For example, today’s Watch is an accessory (“other hardware”) that supports the iPhone, but some day it may become a full-fledged personal computer. As for a putative car, we have plenty of time…

To be sure, in the best managed companies that have a culture where everyone just knows “What we do here,” a short, resonant motto isn’t really necessary to rally the troops. But too often, a short, forceful declaration that would help clarify a company’s purpose goes wanting. Instead, we hear mealy-mouthed “vision statements” that are afraid to embrace and name the company’s actual goals.

Some companies forgo “What we do here” entirely because the corporate structure is a maze…and thus we circle back to the Verizon Monday Note: The mission statement for Verizon/AOL/Yahoo is impossible to construct; the agglomeration is en route to mediocrity.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.