Long before he was elected president, Rodrigo Duterte let Beijing know the South China Sea was theirs

Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte has made frequent appearances in the international headlines in the past few months. Since coming to power in late June, the former Davao City has mayor has come across as wildly unpredictable at times, with his coarse language, emotional outbursts, and his seemingly sudden pivot to China.

Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte has made frequent appearances in the international headlines in the past few months. Since coming to power in late June, the former Davao City has mayor has come across as wildly unpredictable at times, with his coarse language, emotional outbursts, and his seemingly sudden pivot to China.

The latter has certainly been newsworthy, but it hasn’t been surprising—at least to anyone who happened to watch a news segment by CCTV News, China’s state broadcaster, posted online in May.

“The guy is saying exactly what he’s saying now,” said Richard Javad Heydarian, a political scientist at De La Salle University in Manila. “It’s not like he was hiding anything. It’s just that people in the Philippines were not paying attention.”

In the video Duterte (coming in at the 1:33 mark) questions the usefulness of a case then winding its way through an international tribunal, in which Manila challenged China’s maritime aggression against the Philippines. He notes that any decision the tribunal reaches would be unenforceable by the United Nations.

“If we cannot enforce, and if the United Nations cannot enforce its judgment, then what the heck?” he says in the video. “What are we supposed to do? Just sit there and wait for somebody to take our cudgels and go to war or demand obedience from China? For what?”

The CCTV segment narrator adds (at the 1:55 mark), “And if it were up to him, he says he would not count on the Americans coming to the Philippines’s rescue, and would have even considered dropping an arbitration case the Aquino administration filed against China.”

The timing of this is important. Heydarian, who also appeared in the segment, said he was interviewed for it in early May. The CCTV reporter told him Duterte’s interview was conducted earlier, in March or February. Duterte, described in the segment as the frontrunner, won the election in late May, taking office in late June. The tribunal issued its ruling in mid-July. So Duterte had made up his mind about the case, whatever the outcome, well before the ruling was issued or he won the election—and Beijing knew it all along.

The case had been initiated by the Philippines in 2013, under the administration of then-president Benigno Aquino III, and in response to aggressive tactics by China in the South China Sea. Handling the case was the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, ruling under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

In 2012 China seized Scarborough Shoal, a strategically located reef near the Philippine coast, and started blocking Filipino fishermen from operating there, even though they’d relied on the area’s rich fishing grounds for generations. It also prevented Philippine attempts to explore for oil and and natural gas within its own exclusive economic zone (EEZ), despite the country’s sole right to natural resources there, per UNCLOS.

China insists that a ”nine-dash line“ it has drawn, encompassing most of the sea, defines its territory, even if it overlaps with another nation’s EEZ, as it does with about 80% of the Philippines’ zone. China is insisting on ”joint development” of the resources—claiming, in effect, a cut of the profits from the Philippines’ assets.

The tribunal ruled in mid-July that China’s actions were illegal under UNCLOS, and it invalidated the nine-dash line. The Philippines erupted in celebration, with #chexit (“China exit”) becoming a popular hashtag on social media and the international community calling upon Beijing to abide by the ruling. With more than $5 trillion in global trade passing through the sea annually, many nations have a vested interest in keeping it open, and are unsettled by China’s claim.

Beijing vowed to ignore the decision and pressured others to do the same. Still, it was easy to imagine at the time that Beijing was sweating bullets over the tribunal’s ruling, though as the CCTV segment suggests, it probably never was. Perhaps Manila would leverage the legal victory to rally international public opinion against China, and help other nations around the South China Sea, like Vietnam and Malaysia, bring their own legal fights against China’s maritime aggression.

Beijing insisted all along on bilateral negotiations only, with no outside third party involved—especially some international tribunal. That policy went for the Philippines as well as for any other claimant nation in the sea. But many in the Philippines were against this, noting the arrangement would give far too much power to China, which dwarfs the Philippines economically and militarily and could easily overpower it in any negotiations or conflict—as it could most Southeast Asian nations.

Right after the July 12 ruling, the Philippines’ lead lawyer in the case, Paul Reichler, laid out a scenario in which the Philippines and other claimant nations around the South China Sea could band together against China’s aggression:

“If these other states stand up for their rights in the way that the Philippines has done, you get a situation where all of the relevant neighboring states are insisting that China withdraw its illegal claims and respect their legal rights, which have been defined and recognized and acknowledged today because those states have the same rights as the Philippines. It will depend to a great extent on how vigorously that all of the affected states—all of the states who have been prejudiced by the nine-dash line—assert their rights against China. When I use words like ‘vigorous’ and ‘assert,’ I’m talking about diplomatically, legally, and, above all, peacefully… If the other states refuse to be intimidated and continue to insist that their rights under the Law of the Sea convention be respected by China, as well as the rights of the Philippines, if they can work together in unity, you may see a different response from China in six months or in a year, or two years”

But Duterte, for whatever reason, ignored this notion of international teamwork, framing the situation instead as a choice between either going to war with China, or negotiating directly with it.

So it appears that for both Duterte and Beijing, the ecstatic reaction to the legal “victory” was, all along, a passing phase they simply had to patiently wait out.

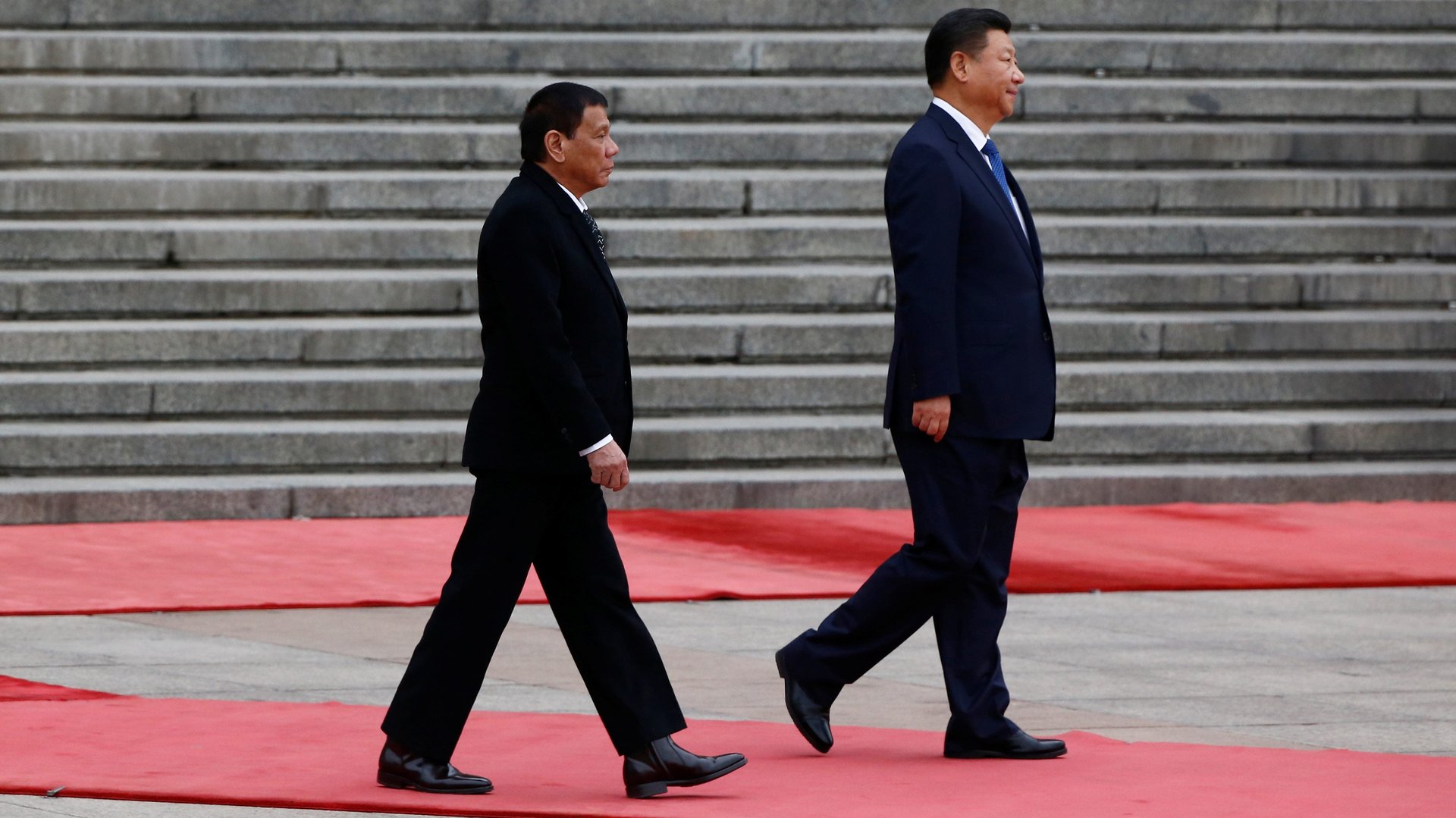

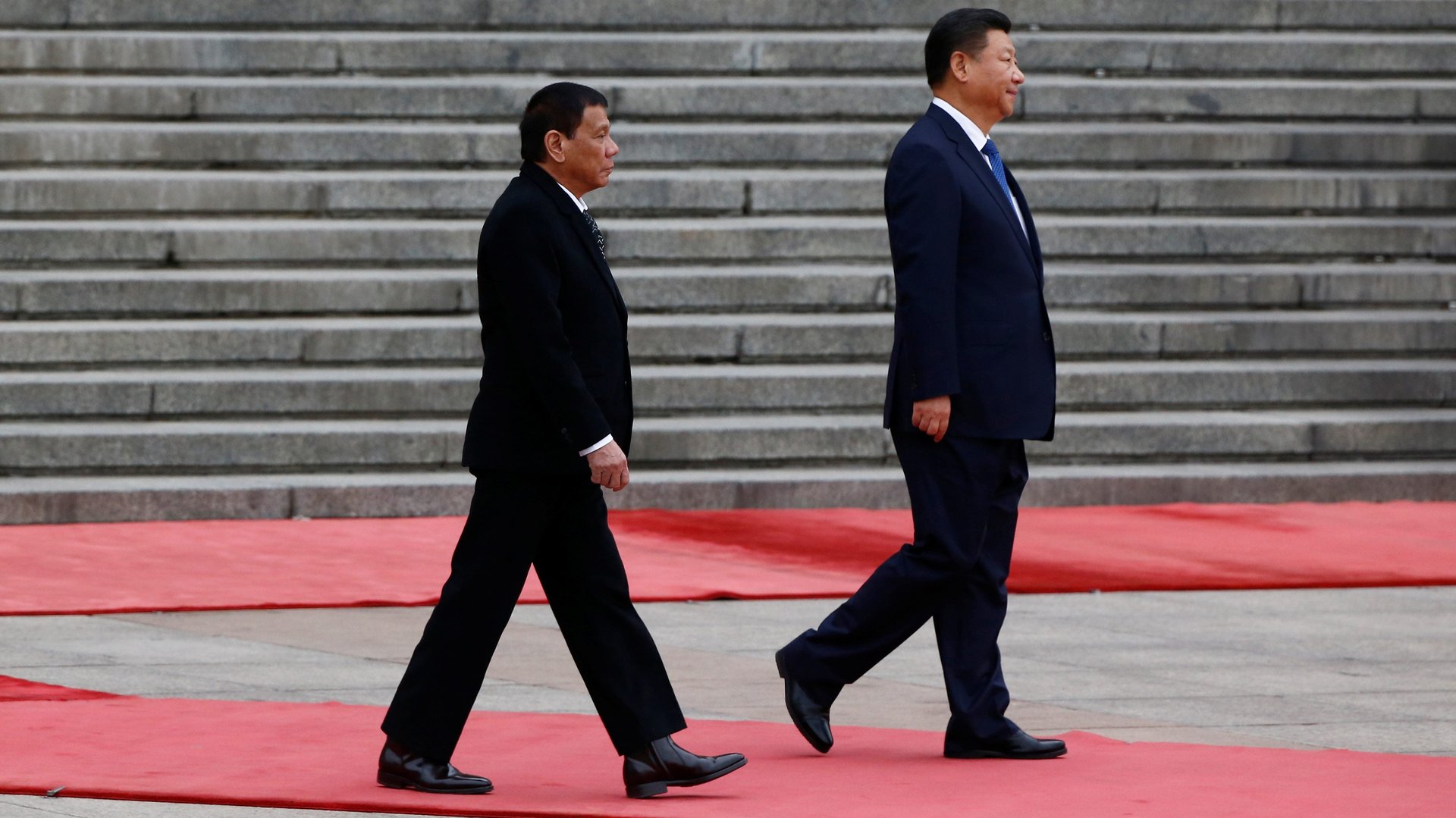

Last week—about 90 days after coming to power—Duterte made his first state visit to a major country. Not surprisingly, it was China. Actually it was surprising, to those unaware of what Duterte’s intentions were all along, because traditionally a state visit to longtime ally the United States would come first. But it was not surprising to anyone who saw the segment on CCTV—a state broadcaster controlled by Beijing.

Many have supposed that Duterte moved away from the US and toward China because of US criticism over Duterte’s bloody war on drugs, with its flagrant human rights violations and extrajudicial killings. But as the CCTV segment suggests, Duterte was leaning toward China regardless.

Duterte seems more concerned with getting help from Beijing with developing infrastructure, including railways, than with defending his nation’s legal rights in the South China Sea. Indeed last week he suggested the tribunal ruling was nothing more than a “piece of paper with four corners”—dismissing the ruling much as he did the case earlier this year.

“Multilateral or bilateral, it’s the same,” he said in the CCTV interview in May. “We have to talk and what I need from China is not anger. What I need from China is help to develop my country.”

And as for Scarborough Shoal, Duterte didn’t seem interested in challenging China on seizing that in 2012 and making it off-limits to Filipino fishermen. Instead he said he “may” be able to get access to it again. (It would likely be conditional access at best.)

That’s as close as Duterte can legally get to basically letting China keep the reef it seized. Under the Philippine constitution it would be an impeachable offense for Duterte to give up the nation’s sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal (called Panatag Shoal in the Philippines).

And indeed, in exchange for agreeing last week to the bilateral talks Beijing wanted all along, Duterte scored billions of dollars worth of soft loans and credit facilities from China, and signed 13 memorandums of understanding, including one related to transportation and infrastructure projects. He also put pressure on Japan, already the top investor in the Philippines, to invest even more in his nation. (He followed his state visit to China with one to Japan.)

But China illegally seized Scarborough Shoal for a reason—not just for the fish, but because of its location. By building a militarized island there, as it’s done atop other reefs in the South China Sea in recent years, it could form a strategic triangle for monitoring and controlling the entire sea, and turning it into, as some analysts fear, a “Chinese lake” subject to the will of Beijing.

That would be good for neither international law, global and regional trade, nor, in the long run, the Philippines—no matter how many new trains or soft loans China provides.