On the TV show Westworld, when the character of William arrives, he’s thrust into a lawless environment loosely based on the old American West where people live out their deepest, darkest, and most depraved fantasies with robotic “hosts.” Such an experience does not come cheap in the HBO show. Early on, William’s friend mentions in passing that they are each paying a cool $40,000 a day for their once-in-a-lifetime trips.

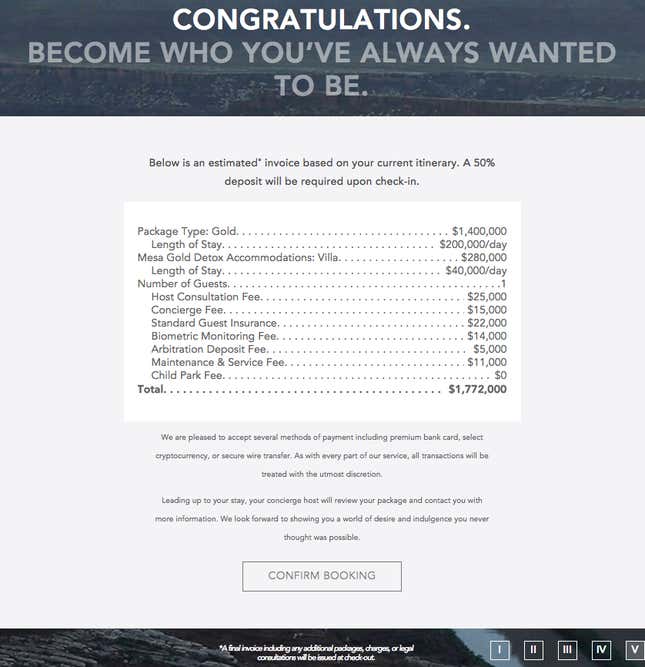

In fact, that’s just the base rate. HBO had some fun promoting the series with an impressive website called Discover Westworld, where guests could book trips to the fictional park. (The terms and conditions state that you’re not allowed to sue if you die from autoerotic asphyxiation—or the hosts attacking you.) It turns out that the fictional Westworld offers three different packages, each with a minimum one-week stay:

- Standard, starts at the beginning of the park with a private consultation during which guests pick their hats and weapons: $40,000 per day

- Silver, allows guests to bypass standard game play and move further into the park more quickly: $75,000 per day

- Gold, offers access to secret paths that bring guests straight to the outer fringes of the park: $200,000 per day

Ed Harris’s Man in Black—who (spoiler alert!) may in fact be William and might even own the park—likely took the gold package as he tries to get to the center of the maze.

But this got us thinking: if you tried to make a Westworld today, how would go about it? Westworld may be pure fantasy, a souped-up dude ranch. But—murderous self-aware AI robots aside—it’s the way that attractions, theme parks, and recreational experiences are going. The old-fashioned theme park is becoming immersive.

‘Exploring what stories are’

New technology has enabled theme-park and attraction owners like Disney, Warner Bros., and Universal Studios to recreate some of today’s most popular films and creative properties in the real world.

In 2012, Warner Bros. used many of the props and sets from the Harry Potter movies to build an immersive tour near the London film studios where the iconic movies were made, which offered the full Hogwarts experience. Visitors can get a Butterbeer, fly on broomsticks, and drink Gillywater—regular old bottled water that references the films. Universal Studios recreated the Wizarding World, too.

And it’s true of another rapidly expanding universe based in a galaxy far, far away. Disneyland’s largest single-themed expansion—ever— is an upcoming, 14-acre immersive Star Wars land that will feature the Millennium Falcon, introduce park goers to new worlds, and possibly even allow them to engage in lightsaber battles that look and feel real.

It’s a long way from the Disney’s first Star Wars attraction from 1987—a simulator ride called “Star Tours” that took passengers on a virtual journey to the forest moon of Endor.

But perhaps the coolest variation on the theme has been the immersive theater company Secret Cinema. The London-based cinema stages massive events that build worlds around famous films, in which theatergoers actually dress up and participate in a story.

For example, for a 2015 production of The Empire Strikes Back, Secret Cinema transformed an old newspaper factory in East London into a cargo hangar that was used to transport theatergoers, who played refugees of the Clone Wars, to the rebellion. The event culminated in a screening of the movie. Tickets were not cheap—starting at £75 ($94 at the time)—but it was extremely popular. More than 100,000 people participated during the show’s four-month run.

In 2014, it actually reconstructed the main town square from the Back to the Future films.

Fabien Riggall, the creative director at Secret Cinema, tells Quartz he remembers going to a local theater in Morocco as a child and buying a ticket for the Sergio Leone gangster epic Once Upon a Time in America. He was 11, about the same age as the main character, and he became completely engrossed in it. ”I became the central character,” he reminisces. “That was for me the moment when I really, really got passionate about going to see movies.” That began a lifelong fascination with trying to change the way people experience cinema—to make them feel as though they’re apart of it.

“What if you could essentially live the movie?” he thought to himself, which was the initial concept of Secret Cinema. ”We know exactly what we want the audience to feel, what we want them to explore, what we want them to go in.”

“It’s very much about knowing exactly what the audience is going to be doing,” he added, sounding very much like a kinder, gentler version of Anthony Hopkins’s malevolent Robert Ford on Westworld.

Like the HBO show, Secret Cinema sells tickets to its events through a digital portal where guests are assigned roles to play. (In Westworld, visitors pick their roles.) Both concepts also have story loops—Secret Cinema holds multiple showings of its productions, of which there have been more than 40, and the hosts in Westworld repeat their narratives each time they re-enter the park. Those storylines keep visitors rooted in their respective worlds.

“When I saw the TV show,”said Riggall of Westworld, ”I just thought it’s a really interesting, really unusual form of storytelling. It’s exploring what stories are and the way that stories are told.”

For the record, his team has no plans to do a version of the show. But what if someone tried to create the world of Westworld now? Given that theme parks and attractions are advancing everyday, it’s conceivable that a company could build a Westworld-like experience in real-life at this point in time. It’d just be an enormous, time-consuming, and expensive undertaking.

The Quartz guide to making Westworld real

Firstly, guests would have to follow some of the show’s protocols—they would have to check all anachronistic technology at the door and need clothing, accessories, and money that fit with the time period. You’d also have to limit the number of guests. After all, there are no queues in Westworld.

“You would want to eliminate anything that takes you out of the experience,” said Craig Hanna, chief creative officer at Thinkwell Group, a creative agency that plans and develops attractions like the Warner Bros. Studio Tour.

You would need a controlled environment, like a closed-off area in the desert or a cruise ship. You’d have to fill it with actors, sets, and props. It would take months or years of careful preparation, production, and scripting. (Each of Secret Cinema’s productions take six to nine months of preparation, for example.)

Disney reportedly shelled out an estimated $500 million to build an immersive recreation of Avatar’s Pandora, which is slated to open next year. The first section of Universal Studios’ Wizarding World of Harry Potter reportedly cost $250 million to build, and the add-on that houses Diagon Alley cost an additional $400 million—which is connected by train, much the same way the the different parts of Westworld are. And Disneyland’s new Star Wars land is part of an estimated $3-4 billion expansion that also includes changes to the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and other parts of the park. Secret Cinema won’t say how much its events cost.

Something like Westworld would likely cost even more because of the scale and complicated logistics behind it. “That’s probably why this hasn’t happened yet,” said Hanna at Thinkwell. “The only people who could pull it off are major corporations and they’re all beholden to boards and shareholders.”

All of whom would also be put off by how much sex there is in Westworld. As Quartz’s Allison Schrager wrote about in a series on the economics of a high-end chain of Nevada brothels, where the prostitutes can make six-figures a year, a real-life sexual encounter would not come cheap. The “girlfriend experience” (of which there are admittedly few on the show) costs about $1,000 an hour, if our real-life Westworld was to be truly authentic.

There’s another hurdle that would be difficult to overcome without the fictional technology that enables the park’s hosts. ”Westworld’s only difference is that you get to wreak havoc in it,” said John Gerner, a longtime theme-park consultant and managing director Leisure Business Advisors. “It’s much more visceral.”

You wouldn’t be able to provide a good substitute for maiming and killing. Modern animatronics are not yet good enough. With actors playing the hosts, visitors couldn’t physically harm them. Gunslingers could be given props for staged shootouts, but there would have to be rules to prevent people from getting in fist fights, or worse. It could be fairly easy to do a more violent, non-lethal version of paintball, however.

To capture the real Westworld vibe, the experience would also have to last more than one day, which is rare for attractions. Secret Cinema’s events, for example, last about four to six hours, including the movie. But in Westworld, visitors remain in the park, sleeping in saloons or on train cars, for the duration of their stay. Disney offers accommodations on site, and rooms at one of its swankiest resorts in Orlando, Florida start at $574 per night, for comparison. A luxury cruise can cost $400-$900 per person per day.

This would require about three actors for every role, Hanna estimated, to keep the show running 24/7. Assuming the park has a five-to-one ratio of hosts to visitors, which seems about right based on the show, that’d be about 4,500 cast members for every 300 guests. That’s not cheap.

Character performers on Disney Cruises make about $65.75 per day, according to Glassdoor. That’s a low estimate considering the extensive training the actors in a Westworld-like scenario would need, but using that figure, it’d round out to about $300,000 per day in running costs just in actors. That’s not including the numerous behind-the-scenes production personnel who—unlike Bernard—can’t yet be robots.

Add in the set maintenance, fake bullets, explosions, and buckets and buckets of fake blood—and the experience would be even more costly.

HBO’s own $400,000-plus price-tag per week to truly live out one’s fantasies in the park doesn’t seem that unreasonable compared to what it would cost a consumer to do it properly today, without Westworld’s advanced technology.

And, much like the human characters of the show, there may be a market among the ultra-rich for such an experience—even at those prices. Gerner and Hanna both compared it to Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, which sold hundreds of tickets starting at $250,000 paid upfront—before ever launching a single customer into orbit—for three days of training and less than three hours in space. “There’s clearly an echelon of people in this world that can afford to do this stuff,” Hanna said. “If you said, live out your fantasies and you were able to do what Westworld does.”

He added: “I think you’re going to get a lot of people saying, how much is that going to cost? I’m in.”