China’s anti-corruption agency just released a TV series about corruption in the agency

The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) of the Chinese Communist Party is the agency that steers president Xi Jinping’s ruthless anti-corruption campaign that has netted thousands of party officials in the past years.

The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) of the Chinese Communist Party is the agency that steers president Xi Jinping’s ruthless anti-corruption campaign that has netted thousands of party officials in the past years.

But the graft-buster is itself corrupt.

A new TV series, titled To Forge Iron, One Must be Strong—a phrase Xi used when he vowed to wage war against graft when he took office four years ago—details for the first time the corruption cases of former senior anti-graft officials. The three-part TV series is co-produced by the CCDI and state broadcaster CCTV. The first episode, broadcast on CCTV last night (Jan. 3), features the confessions of three of the 10 corrupt CCDI officials starring in the series. The video and its full script are available (link in Chinese) on the CCDI website.

The TV series comes on the eve of a key meeting of the CCDI that kicks off on Jan. 6 (link in Chinese). It also isn’t the first time Chinese viewers have been able to enjoy a series about China’s anti-corruption campaign. In October, an eight-part series featuring dozens of corrupt officials called Always on the Road was broadcast ahead of the party’s sixth plenum meeting.

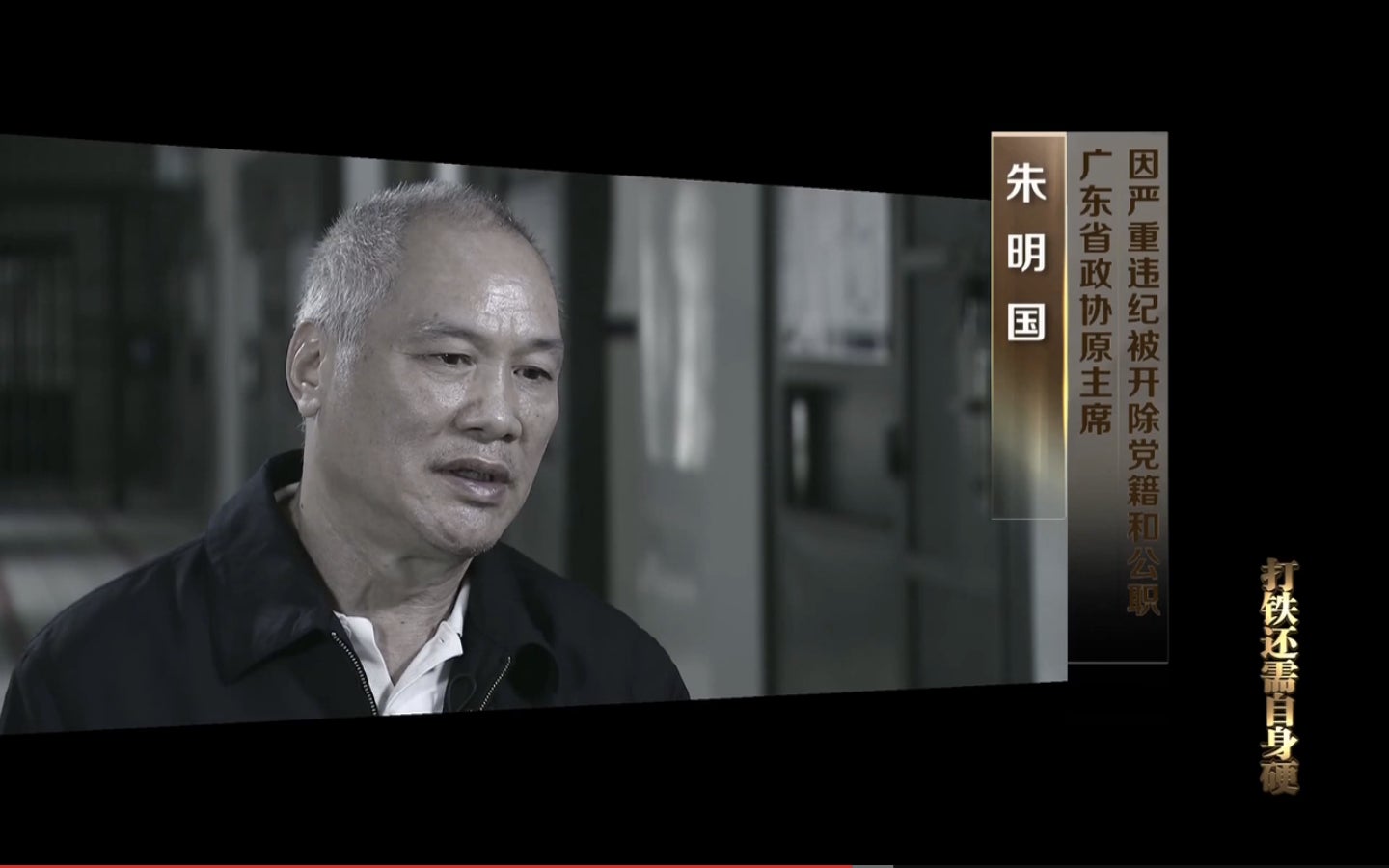

The three anti-graft officials featured in the pilot episode of the latest series include Wei Jian, who oversaw corruption cases in the state-owned financial sector; Luo Kai, who was in charge of investigations of corrupt officials in local governments, and Zhu Mingguo, former CCDI head in Guangdong province who recently received a suspended death sentence for taking bribes. The trio confessed on camera that they accepted bribes including gold, booze, and property.

The message of the series is that the CCDI, left unchecked, ends up wielding too much power in China’s anti-graft drive—and thus becomes corrupt itself.

“A CCDI secretary’s view of a cadre or a party member can decide whether he gets promoted or demoted in his life, or at least for a period of time,” said Zhu the former Guangdong CCDI boss, explaining why his power extended so far. “So ordinary officials are afraid of the CCDI. This is for sure.”

Luo compared the CCDI’s role to the “investigating censors” in imperial China, who controlled all officials, inspected local authorities, and directly reported to the emperors, and said that they were ”three ranks higher” than officials who were nominally on the same level as them.

In 2014, the CCDI established a sub-office to investigate corruption among its own officials. A recent report from Human Rights Watch exposed first-hand accounts of torture in an extra-judicial detention system used by the CCDI and its local bureaus to coerce confessions.