Compared to the panoply of problems companies could face, stockpiling too much cash is perhaps the least troublesome. But it is trouble, nevertheless.

Don’t get us wrong, corporations are designed to make money, and when a company spews giant plumes of cash—like Apple has over the last few years—it’s usually a much better indicator that things are going well than many of the mushy metrics in a quarterly financial statement.

The problems start when managers decide to keep that money in the corporate coffers and not return it to the people it belongs to: the shareholders. That’s been the consensus for decades among scholars of agency theory, a branch of economics that studies the relationship between corporations and the managers that run them. In theory, corporations exist to enrich shareholders. But in practice, managers are subject to incentives that don’t necessarily align with those of shareholders.

Cash piles are a textbook example. CEOs tend to want to keep cash under their control—it gives them flexibility and puts them in a strong position to make growth-based investments. Often this doesn’t really work out well for shareholders. As the Journal’s Jason Zweig put it in a column (paywall) a while back:

Excess cash can goad chief executives into making impulsive acquisitions at high prices, splurging on palatial headquarters or overfunding underwhelming projects. In fact, academic research shows that companies with the highest levels of cash go on to become less profitable in the long term; one recent study found that high-cash firms earn future profit margins 1.5 percentage points lower than those that carry the least cash.

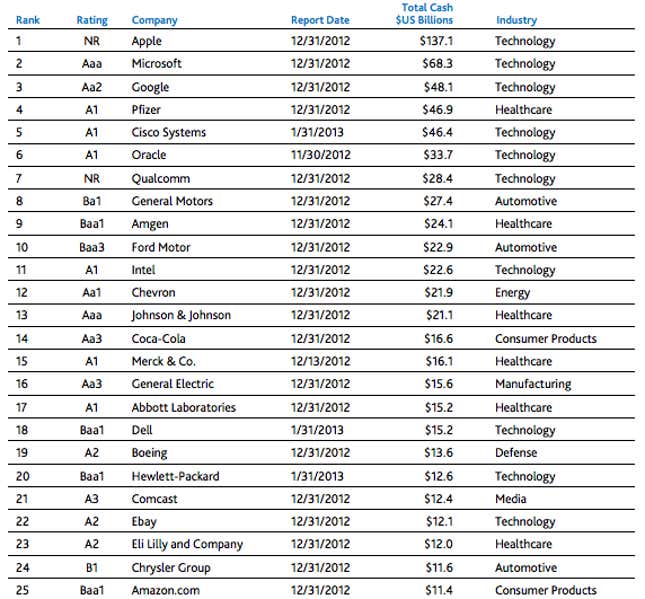

So, the question is: What companies could be at risk of such dynamics? Not too long ago, Moody’s cobbled together this list of the largest cash holdings among US nonfinancial companies at the end of 2012. Here’s the top 25:

Both Apple and Microsoft are handing buckets of money back to investors via their dividend programs. That leaves Google as the outlier. The search giant hasn’t paid a dividend since its 2004 IPO. Now, don’t get us wrong. Google is a tremendous company. Earnings have been good. Share are up 25% so far this year. But in the context of agency theory, Google’s forays into wearable computing, driverless cars and efforts to wire all of Kansas City, Mo. look somewhat scattered.

And if Google skirts dividends for too long, activist investors are sure to start agitating for shareholder payouts. Just look at what David Einhorn did to push Apple to create a new class of preferred stock.