Much has been said about the original iPhone’s success factors: an innovative multi-touch interface, a never-seen-before combination of cell phone, iPod, and internet “navigator.” All good, but missing one crucial element: removing the carrier’s control on the iPhone’s features and content.

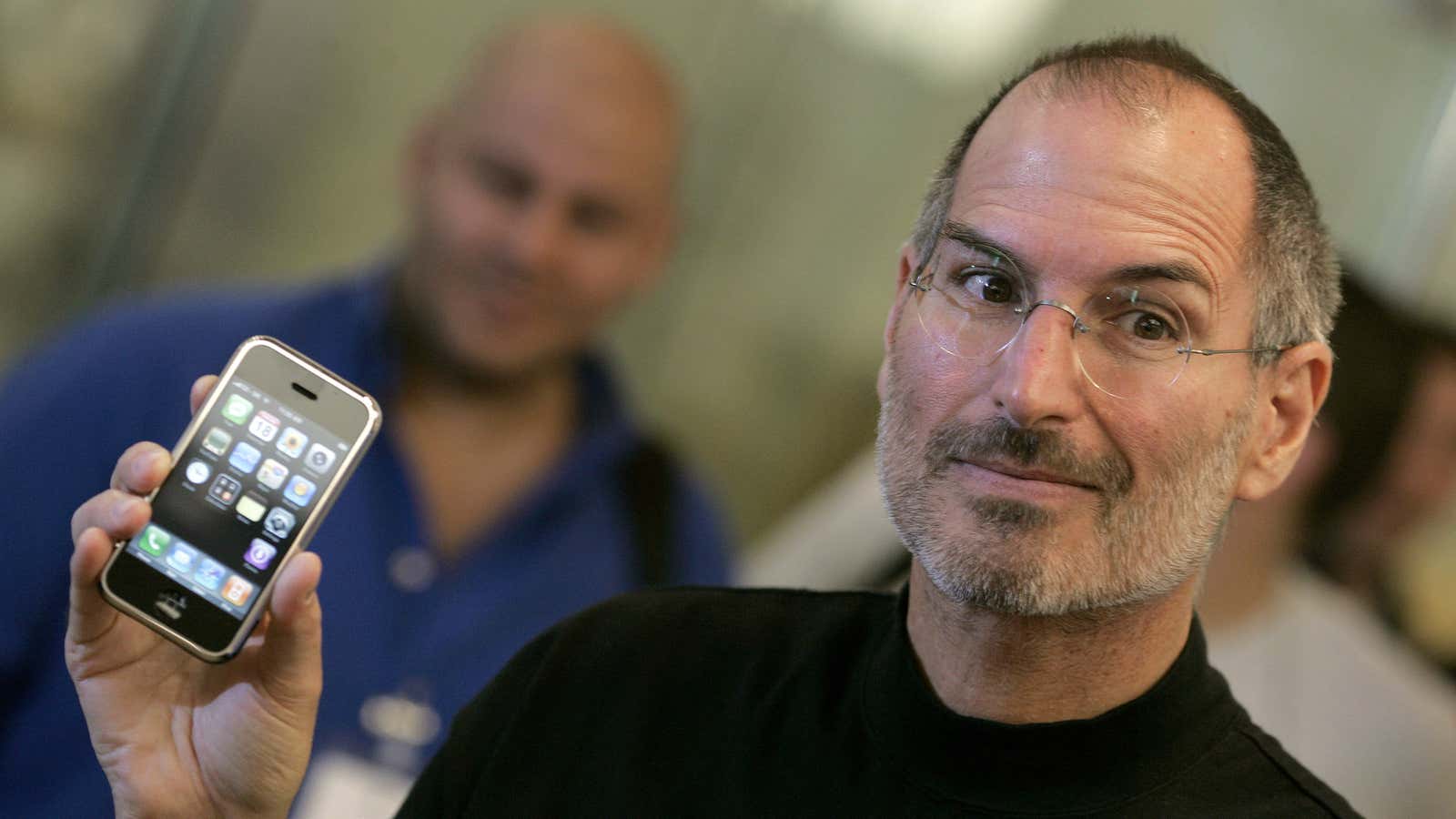

The iPhone’s 10th birthday was a happy opportunity to look once again at Steve Jobs’ masterclass in storytelling and positioning, and to contemplate, with incredulous gratitude, the enormity of the consequences. As Horace Dediu, our nonpareil tech historian and poet, recently remarked with his trademark humor, “The First Trillion Dollars is Always the Hardest“ [as always, edits and emphasis mine]:

In its first 10 years, the iPhone will have sold at least 1.2 billion units, making it the most successful product of all time. The iPhone also enabled the iOS empire which includes the iPod touch, the iPad, the Apple Watch and Apple TV whose combined total unit sales will reach 1.75 billion units over 10 years. This total is likely to top 2 billion units by the end of 2018.

[…] iOS will have generated over $1 trillion in revenues for Apple sometime this year.

In addition, developers building apps for iOS have been paid $60 billion. The rate of payments has now reached $20 billion/yr.

No one saw it coming, Apple execs included. For their part, the high tech incumbents made many infelicitous statements, only to be steamrolled when the iPhone and, later, Android changed everything. The Smartphone 2.0 wasn’t just a one-to-one communication device, it influenced media creation and consumption, transformed everyday commerce with in-phone wallets and touch ID, turned social networking into a ubiquitous tool. It even forced Enterprise information systems to completely rethink and retool their infrastructure — this wasn’t simply a computer with a “smaller form factor.”

In retrospect, the ascendency of Smartphone 2.0 and the way it has shaped our culture seems obvious and natural. But the celebration and contemplation overlooks a crucial sine qua non, a necessary (but not sufficient) condition: Unlocking the carriers’ grip on handset specifications, marketing, and content distribution.

More specifically, we owe Steve Jobs an enormous debt of gratitude for breaking the carriers’ backs (to avoid a more colorful phrase).

Before the iPhone, handsets received the same treatment as containers of yogurt in a supermarket chain. The central purchasing office told the yogurt makers which flavors to ship, when, where, at what price, with payment at some point in the future after we’re sure there are no more returns. And don’t forget to send your people to make sure the labels line up on the shelves..

Carriers were no less imperious in their treatment of handset makers. They ran the show, never letting anyone forget the Hollywood “Content is King, but Distribution is King Kong” adage. Life was orderly, everyone in the cellphone ecosystem knew their place.

This was anathema to Jobs, himself notoriously control-hungry. He wasn’t going to allow mere carriers to control what the iPhone did and contained. Although the iPhone boasted only Web apps at the announcement, there were native apps, an iPhone SDK, and the App Store gestating and waiting for the freedom to deploy. Letting a carrier dictate — or, worse, design — the apps that would run on the iPhone and manage content… that was unthinkable.

How did Jobs and his team manage to hypnotize AT&T’s execs into giving up their birthright, their control, in exchange for five-year exclusivity on an unproven device they weren’t even allowed to see? But why should we be surprised? Apple’s CEO had performed a similar feat with iTunes back in the iPod days. He convinced publishers to sell music “by the slice,” one song at a time vs. the established album format, and he convinced credit card companies to accept $.99 micropayments.

(In more ways than one, the iPod feels like a large scale rehearsal for the iPhone: hardware miniaturization, supply chain management, content distribution, business model. In addition, the iPod gave the then-beleaguered Apple an aura of success. The company was winning again.)

Having wrested control from AT&T, Jobs could run the table, retain sole control over what was in the box and on the screen, over media distribution, software updates, and, in 2008, the App Store that made the iPhone an immensely flexible app phone. As a result, there’s no crapware on the screen, iOS updates are quickly adopted, and security holes are more rapidly plugged.

After AT&T’s capitulation, the other carriers soon followed. They didn’t like the loss of control and they complained about subsidies even as they signed up more and more subscribers, all leading to Horace’s $1 trillion number.

To be sure, Jobs’ way isn’t the only path. Carrier control over Android handsets didn’t prevent the Google platform from becoming wildly successful…and wild it has been: The Android proliferation comes with fragmentation and low adoption of fresh versions and security fixes. For example, the most recent Android version (last May) had 7.5% adoption versus 84% for iOS 9.

In addition to a “free” business model that gets nowhere near Apple’s revenue numbers, Google has long been frustrated by the slow, carrier-throttled updates and crapware: “This is not how Android should be deployed.” In reaction, Google has sold a succession of “pure” Android phones, the latest being the Pixel device, and they’ve experimented with Project Fi experiment, a sort of MVNO (Mobile Virtual Network Operator) that straddles cellular and WiFi. Where Project Fi will lead is unclear, but there would be dancing in the streets if Google or Apple offered a nationwide, no-small-print, cleanly priced network.

Standing atop its $1 trillion mountain in a saturated smartphone market, Apple is now seen as having run out of growth prospects, at least without a new product to ride to new heights. The consensus among today’s observers is that Tim Cook’s recent “the best is yet to come“ statement should be shrugged off, something he had to say rather than a hint that Apple is sitting on a portfolio of to-be-unveiled magical products.

Add a classic PC segment in decline, a Watch that so far hasn’t moved the needle, and a confused Internet of Things with more hyperbole than stable business models, and the sum doesn’t even come close to providing another “2007 iPhone” growth engine.

But we’ll see…anticipating Apple’s doom has never been a safe bet.

In the meantime, let’s have another grateful thought for what Steve Jobs did to keep carriers from messing with the iPhone.