Why worse-than-expected German unemployment could be a good thing for the euro zone

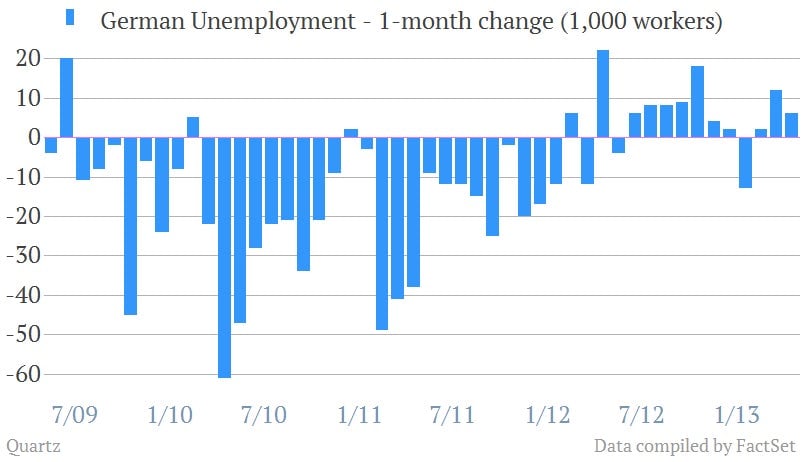

The fourth consecutive monthly rise in German unemployment hints that the gap between the euro zone’s core and its periphery might be slowly closing. Some 21,000 more workers went jobless in May (pdf), in seasonally adjusted terms—four times more than economists expected, based on Bloomberg estimates.

The fourth consecutive monthly rise in German unemployment hints that the gap between the euro zone’s core and its periphery might be slowly closing. Some 21,000 more workers went jobless in May (pdf), in seasonally adjusted terms—four times more than economists expected, based on Bloomberg estimates.

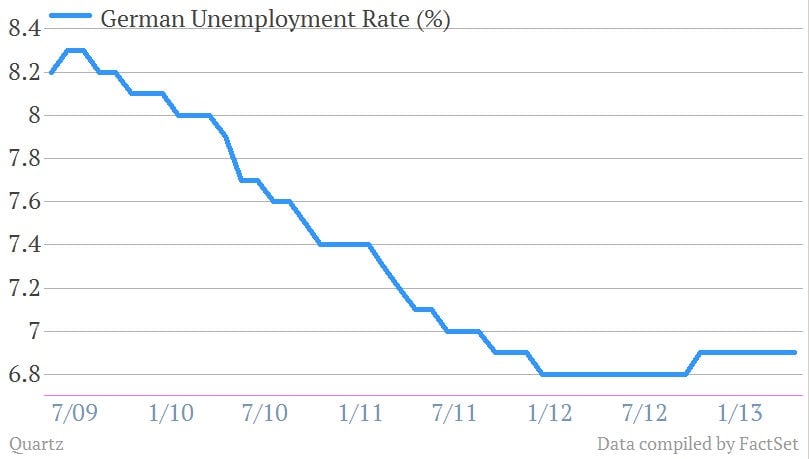

With 2.96 million without work, Germany’s unemployment rate still remains at a relatively low 6.9%, as you can see:

And here’s a look at the uptick in workers without jobs—again, based on seasonal adjustments. (In unadjusted terms the unemployment rate is 6.8%, down from 7.1% in April, and with a net of 83,000 workers actually gaining jobs; but that’s because of the seasonal cycles in the labor market.)

Germany’s GDP increased a mere 0.1% in Q1 of 2013, after having contracted 0.7% in the last quarter of 2012. That’s in no small part due to the withering fortunes of its fellow EU countries, to whom Germany typically sells some 60% of its exports. Though recent business activity data have suggested that the German economy has been stabilizing of late, and business confidence is on the rise as well, the slower-than-expected demand for labor suggests that the recovery is still on shaky ground.

For those who aren’t jobless Germans, though, this could be a good thing. My colleague Simone Foxman recently argued that a softer German economy could help the euro zone as a whole by making German policymakers a bit more tolerant of other countries easing up on austerity measures. And indeed, the European Commission indicated earlier today that it may allow France, Spain and the Netherlands to miss their budget deficit limits (paywall).

Rising German unemployment could also be one step toward rebalancing the euro zone, suggested economist Michael Pettis recently. This is because the origins of the euro-zone crisis lie in Germany’s excess savings relative to its consumption; it exported excess savings and production to neighboring countries, whose own economies ended up being thrown out of whack. Since laid-off German workers have nothing to sock away, but still must consume, this will cut down on Germany’s net export of goods and services, and help correct the imbalance.