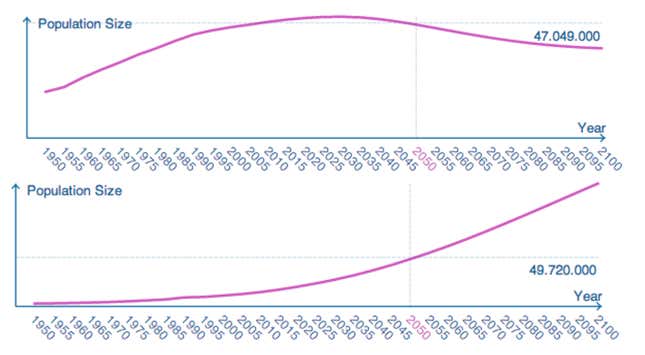

South Korea has way too many old people—and that problem, as we’ve written, is only getting worse. It needs workers to support these seniors. But at its current birthrate, it’s not churning out enough babies to do that.

Malawi doesn’t have that problem. In fact, it has the opposite one. Its population is taking off—it will more than double within the next 30 years—but jobs aren’t keeping up with population growth, so much so that something like 80% of high school graduates can’t find steady work.

That might make a recently-announced South Korean plan to take 100,000 young Malawian workers to staff low-skilled jobs sound like a great idea.

But not to everyone, it seems. The deal sparked outrage among Malawian opposition politicians. And though Joyce Banda, Malawi’s president, says the deal was hammered out back in February, the South Korean government now denies that any such plan is in the works.

Malawi’s government, however, says the deal’s done. That makes sense—South Korea has been aggressively pursuing bilateral deals for recruiting migrant workers. Immigrants now make up 2.8% of the population; the government says it expects them to make up 6% by 2030. Just last year, South Korea unveiled a migrant worker program involving 15 countries, including relatively “young” countries like East Timor and Nepal.

But while some Malawian opposition politicians liken the deal to “slave labor,” others worry about thinning the country’s talent pool.

“We always cry about brain-drain and encourage Malawians in the diaspora to come back home and yet here we are exporting the cream of our labour force abroad,” opposition politician Stevyn Kamwendo said in parliament last week.

Though “slave labor” might be a tad over-the-top, the concern about brain drain isn’t. An exodus of highly skilled medical workers costs sub-Saharan Africa $2 billion per year. Malawi took a big gamble recently, putting its international funding into paying public health workers more as HIV ravaged the country. Fewer nurses are leaving their jobs and many more are enrolling. But in rural areas, the shortage of medical workers is still acute. And a drop-off in foreign aid and in output from Malawi’s tobacco industry have drained government coffers, as a recent currency devaluation causes the cost of living to soar.

The brain-drain complaint could also seem silly given that South Korea is (allegedly) recruiting for low-skilled factory jobs. But the deal would pay workers $1,380 a month, alongside free housing and electricity. (Although accounts differ, there are reports that workers will get only about $125 of that, with the rest deposited in Malawi as savings). Compare that with an entry-level nurse’s wages of $60-150 a month in Malawi. Even if the jobs in Korea are low-skilled, the high wages could attract talented Malawians who would otherwise train as medical workers back home. Already, 15,000 have applied for the program, says the Malawian labor minister.

Given that Malawi says 300 workers will “leave very soon,” South Korea needs to straighten things out fast. Even if the entire thing is a misunderstanding, allaying the “slave labor” fear will greatly brighten the prospects of its expanding its guest worker program to Africa—and that would help a lot to soften the impact of its ageing crisis.