Monterrey, Mexico

The help wanted sign outside Carrier’s plant in Monterrey is openly defying US president Donald Trump’s “America First” motto.

“Join this great team!” it insists. “Competitive salary. Transportation. Training. Very good work environment.”

Trump claimed credit for brokering a tax deal last year to keep the air-conditioning and heating company’s factory in Indianapolis from closing. But many of its jobs are nonetheless moving to Mexico, and Carrier’s existing four factories in Monterrey, the country’s northern industrial hub, are hungry for workers. I saw plenty of other hiring notices as I drove around Monterrey’s industrial parks earlier this year.

Why is this little-known (to Americans, anyway) city plucking jobs out of the American Midwest? As a Monterrey native, I have an idea—and it’s not just because of low wages.

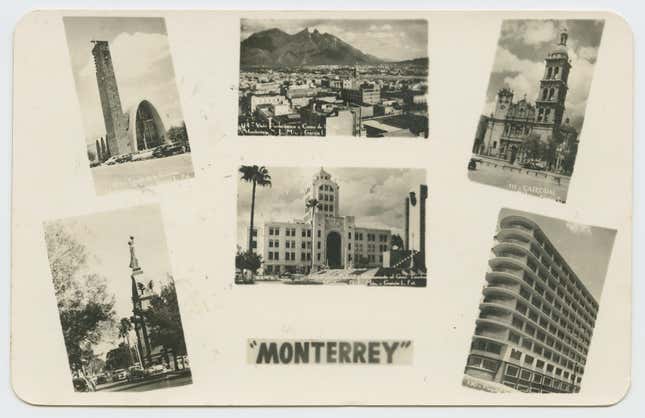

Just 150 miles (240 km) south of the border, Monterrey is in many ways more attuned to the US than the rest of Mexico. There are no grand colonial buildings or ancient ruins to be seen. Its sprawl, like that of many US cities, is of a more recent vintage and dotted with the same American franchises.

Growing up, I learned math and science in English instead of Spanish. Like me, many regiomontanos—as locals are known—travel to Texas more often than to Mexico City. The Dallas Cowboys football team has a huge and devoted following.

This predisposition to look north goes back generations, scholars tell me, and has made regios naturals at globalization. Well before the term was coined, the city’s early industrialists were deep in business deals with American companies. By the time the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) came around, in 1994, the city had accumulated decades’ worth of expertise on how to draw foreign companies.

This week the US, Mexico, and Canada launched into a renegotiation of Nafta, prompted by Trump, who has called it the “worst deal ever.” But it’s going to take much more than changes to a treaty or Trumpian bullying to erase the lead Monterrey has developed not only over Mexican cities farther south but also over the American Rust Belt communities that voted heavily for Trump.

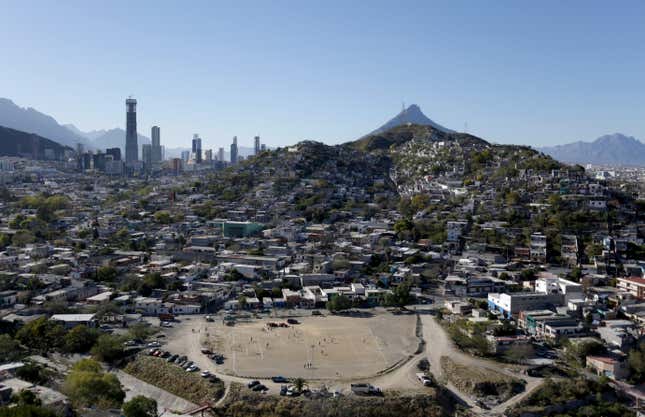

Yet if Monterrey looks like a winner in the globalization game, the yellowish haze hovering over the city and the haphazard development swallowing up its hilly terrain are reminders it’s a big loser as well. Its experience offers a lengthy list of do’s and don’ts for other places struggling to spread the benefits of an integrated global economy more evenly.

Globalization pioneers

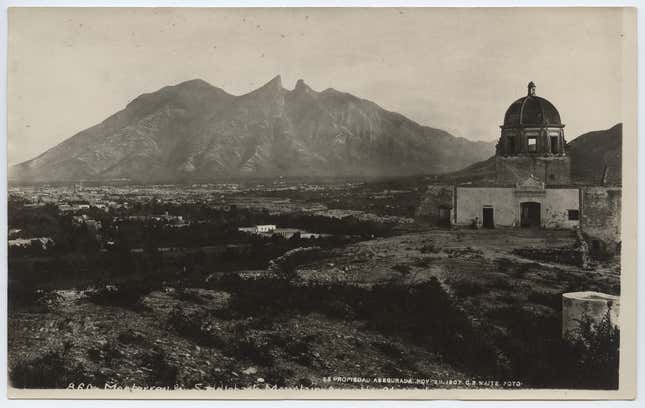

The metropolitan city of our lady of Monterrey was founded in 1596 by a Spaniard accompanied by 12 families in what was then the New Kingdom of León, the wild frontier of Spain’s colony in Mexico. What happened in the following 250 years can be encapsulated, as I learned in school, in the slimmest of textbooks.

Existence in the early days was harsh and precarious, marked by floods and scuffles with local indigenous tribes. Monterrey remained very much an outpost until the middle of the 1800s, when the US invasion of Mexico (1846-48) redrew the international boundary between the two countries along the Rio Grande. Suddenly, Monterrey found itself bordering a burgeoning global power, closer to the US than to Mexico’s capital city.

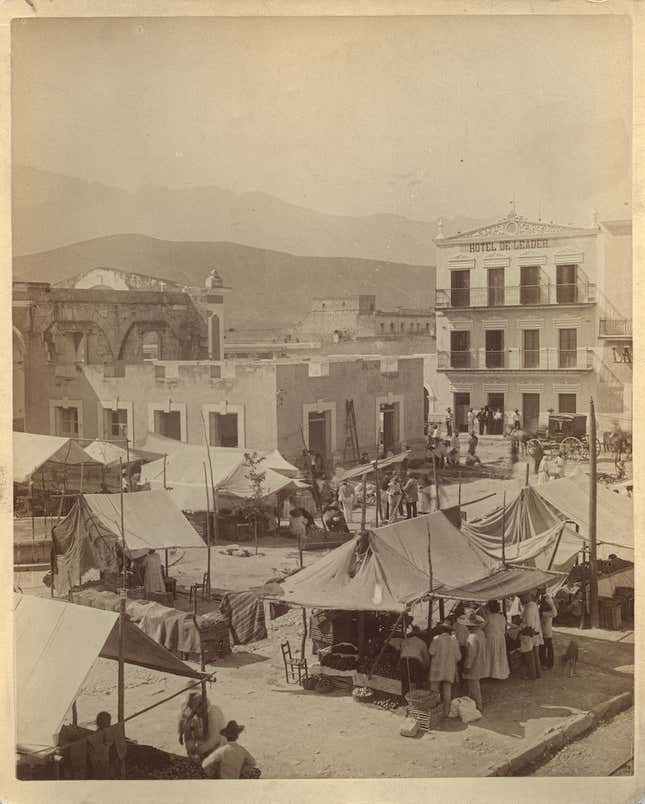

Back then it was the Mexican government that embraced a protectionist bent. The prohibitively high tariffs it set for cheaper American goods produced a profitable smuggling network to sneak them south of the border. The trafficked cargo, including cattle, also flowed north, wrote Patricia Fernández de Castro in a 1994 article (Spanish, pdf) published by the Northern Border College, a research university.

But in the early 1860s, with the Mexican federal government ensnarled in a messy power struggle, the governor of Nuevo León, the state where Monterrey sits, assumed control of the border and opened it up to international trade.

The start of the American Civil War in 1861 multiplied trading opportunities for entrepreneurial regiomontanos. After Union forces blocked southeastern ports, northern Mexico became the main route for Confederate cotton. Monterrey emerged as a major stop along the way.

Local fortunes were also built on selling gunpowder to the Confederate army and food to warn-torn areas. The growing trade between the US and Mexico generated a mule-powered logistics industry that hauled merchandise back and forth.

You could call it the beta edition of Nafta.

After war subsided in the two countries, the Mexican federal government once again took over trade policy. But Nuevo León’s ties with the US remained. The city’s first rail line in 1882 linked it not to the Mexican capital but to the border with Texas. The metal foundries established in Monterrey in the late 1800s to feed American factories helped jumpstart Monterrey’s own industrialization process.

Those kind of connections opened up an alternative business front to local and national markets that the city’s business class still benefits from, according to Mario Cerutti, a professor at Nuevo León’s Autonomous University who has studied the city’s industrial history. They not only favored “a rapid accumulation of capital, but fostered entrepreneurial experience and an ease in relations with the US that would become fundamental in later decades,” he wrote in a book about the economic history of Mexico published by Colombia’s EAFIT University last year.

By the 1960s (pdf), some Monterrey companies were partnering with American firms to make products. Carrier, whose latest Monterrey venture generated so much political angst during the US’s 2016 presidential election, opened its first plant in Monterrey in 1969.

Many more American companies have followed, including two other Trump targets. Last year, Mondelez International moved its Oreo-cookie production from Chicago to the edges of the Monterrey metro area—prompting then-candidate Trump to permanently shun the two-colored cookie in protest. As president-elect, he criticized ball-bearing maker Rexnord’s decision to move production from Indianapolis to Monterrey. (Many Monterrey companies, too, have ventured abroad, creating jobs in Europe, Latin America, and yes, even the United States.)

By 2010, the year of Mexico’s latest census, the inhospitable kingdom of Nuevo León was a bustling state with 4.6 million inhabitants, the vast majority of them in Monterrey’s metropolitan area.

A hefty springboard

Monterrey’s sudden proximity to the US was a windfall that can’t be easily reproduced, but regiomontanos made their own luck as well.

They had much bigger reasons to fear the country across the Rio Grande than Trump does today to fear Mexico. American soldiers invaded and occupied their city (Spanish) in 1846 during the US-Mexican war. Instead of a threat, however, many locals saw the US as rich source of opportunities, and went after them.

The local business elite, some of them European immigrants, built a well-capitalized and diversified corporate apparatus that could quickly adapt and respond to big market changes. They were early adopters of the cluster, or concentration of related businesses—a concept that some prescribe as a globalization survival strategy today. For example, the local beer company, founded in 1890, a few years later formed a glass company to make bottles (with an Ohio-registered patent) and another firm to manufacture bottle caps. In the late 1970s it would start a ubiquitous convenience-store chain that sells, among other things, beer.

Regios were an entrepreneurial bunch too, using family capital and business expertise to branch out into brand-new areas. When Monterrey’s iconic steel company, a mainstay of the local economy since the early 1900s, collapsed in 1986, the rest of the city’s industrial base withstood the shock. A few years later, a batch of newer companies, including auto-part makers, food-processing plants, and telecom operators, had picked up the slack. Meanwhile, the foundry’s rusty carcasses had been repurposed, among other things, as rave dance floors by techno-loving teens.

An MIT for Monterrey

The city’s industrialists were clannish, reshuffling the same last names as scions married other scions, Cerutti’s research shows. But they were also devoted to raising up the rest of the city’s residents, if nothing else to staff their hulking business holdings.

Fundidora, the defunct steel company, started its Steel Schools to educate workers’ children in 1911. A group of entrepreneurs, led by the heir to another industrial empire, founded a new university in 1943. It was modeled after his alma mater (Spanish), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cerutti describes the Technological and Higher Studies Institute of Monterrey, which locals call just the “Tec”, as a human-resources factory that continues to churn out managers and engineers.

It also fosters its founders’ entrepreneurial spirit. The lessons start early, as I an attest. As a high-school student at the Tec, I had to compete in a teenage version of the reality show Shark Tank in which would-be CEOs compete over funding. In our case, the prize was an “A” in an obligatory business course. My collapsing clothes hanger project (very practical for turtlenecks) didn’t propel me into a career of entrepreneurship, but the program (Spanish) which is also offered at the university level, has some impressive results: Five years after graduation, 38% of Tec alumni have been or are partners in a business, and 25 years after graduation the rate goes up to 62%. That penchant for business ownership is also a big part of Monterrey’s job-generating ecosystem.

Decades after its creation, the Tec kept ahead of the times. In 1990, it started an international trade major (Spanish). A freshly-minted batch of graduates was ready to hit the job market just as Nafta was rolled out.

Nafta winnings

The free-trade agreement only intensified Monterrey’s cross-border activities. Not everyone benefitted as Mexico’s new American partners ratcheted up competition. Whataburger swallowed up Mexico’s Burger Boy (Spanish), a childhood favorite where all the sandwiches were dinosaur-themed. Blockbuster—and pirated American cable—displaced (Spanish) the top Mexican video rental chain. Nafta also badly hit the chivera profession (Spanish) the successor to Monterrey’s old-time smugglers. Suddenly the Pampers and Velveeta cheese they trafficked in from the US could be easily found on supermarket shelves—at a lower price than they had charged for it.

But overall, the advantages of the region’s proximity to the US overshadow the losses from the trade deal. In Nafta’s first 10 years, northeastern Mexico, which includes Nuevo León and the three other Mexican states bordering Texas, saw its GDP jump by 57% in real terms, compared to the national average of 36%. Its share of national GDP climbed from 16% in 1993 to 18.6% in 2004, according to a study by Ismael Aguilar, a professor at the Tec.

Nafta winners started emerging within a growing number of industrial parks in the outskirts of town. Between 1999 and 2016, Nuevo León absorbed more than 12% of the country’s foreign direct investment in manufacturing, and 32% of investment in machinery and equipment, according to Aguilar’s calculations.

Under Nafta, Monterrey also plunged deeper into its Americanization. While much of the city still bears the telltale signs of a developing economy—stray dogs, street-invading taco stands, and smog-spewing clunkers are still common—less adventurous expats can totally avoid them by sticking to its most developed areas. There they can find state-of-the-art hospitals, US-accredited schools, and plenty of regios fluent in the language of international business—a marked contrast with Mexican cities farther south. “Culture counts a lot,” says Aguilar. “American investors feel at home here.”

A Korean investment

The Monterrey area now draws investors far beyond the US. Korean automaker Kia recently opened a $3 billion manufacturing facility in the municipality of Pesquería. Until recently, the small community 20 miles east of Monterrey was a handful of city blocks around a small town square.

It’s now an unlikely industrial mecca anchored by Kia’s gigantic facility, which appears to have been teleported from South Korea. From above, its interconnected plants look like a circuit board, one that stretches over 700 soccer fields and is built to churn out a sedan every 53 seconds. Eventually, it will employ 14,000 workers, or the equivalent of 67% of Pesquería’s population.

And that’s just Kia and its direct suppliers, which are embedded in the “circuit board.” Its massive operation has also attracted suppliers of suppliers. Earlier this year, Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto opened a new power plant (Spanish) to feed the area’s bulging industry.

You don’t need econometric formulas to notice Kia’s ripple effect within and outside Pesquería. Just ask a local. Alberto Narvaez used to sit in traffic for two hours on his way to a warehousing job in Monterrey. It now takes him 15 minutes to get to work at a local company that’s part of the Kia production chain. Humble farmers are suddenly wealthy landowners due to exploding real-estate prices, he says. New subdivisions in the area tout their many amenities—in Korean. There are new restaurants, catering to both Koreans and newly-affluent locals.

Some eight miles from Pesquería, tucked in a strip mall near Monterrey’s international airport, is a sleek coffee shop selling scrumptious Japanese and Korean pastries. Its owner, Inwoo Lee, is one of many Koreans lured to Monterrey by the juicy business opportunities that usually sprout around a Kia plant. Business at Lee’s Mad Coffee is good enough for him to consider opening a second shop, this one in a fancy mixed-use development that wouldn’t be out of place in Los Angeles.

Monterrey is not as developed as Seoul, but Lee can imagine how the knowledge transfer from Korean companies could eventually lead Mexico to develop its own industrial giants like Kia or LG.

Can globalization survive?

But globalization is not a self-fulfilling prophecy. Monterrey’s model is under attack from a variety of fronts. If Nafta were canceled, as Trump threatened at one point, Monterrey-made products would become more expensive in the US. Americans might not be as keen on buying a Forte, the main car produced at Kia’s Pesquería plant, if its price were 20% higher. Mexicans’ spending mood would also sour if the domestic economy shrinks—another hit to the demand for Fortes and other items produced locally by the likes of LG and Whirlpool.

The same trend that’s been killing jobs in the US, automation, could also hurt Monterrey’s economy. Hyper-precise robots already do most of the molding and welding at Kia’s factory, for example.

The demise of globalization, though, could also be self-inflicted. While Monterrey has proved to be a master at racking up Nafta winnings, it’s been pretty incompetent at administering them. Lee himself pinpointed a big part of the problem as we chatted over Mad coffee. The Kia plant hasn’t brought the local economy such big benefits in Monterrey as in other places because, instead of cascading down, some of the investment is getting tangled up in corruption, he says.

His diagnosis is not far-fetched. The governor (paywall) who signed off on the Kia deal, a member of Peña Nieto’s party, the PRI, is under investigation for mismanagement of state resources (Spanish). (He denies any wrongdoing.) The new governor, an independent known as “El Bronco,” called his predecessor’s incentives to attract Kia “an exaggeration that threatened the state’s dignity.” He has scaled them down (Spanish).

Whether due to corruption or ineptitude, Nuevo León officials have not been able to spread the benefits of the state’s brisk economic growth. From 2005 to 2015, the state’s GDP expanded by an annual average of 4% in real terms; omitting the 2008 recession, which was brutal for the local economy, the average pace of growth was 5.5% a year.

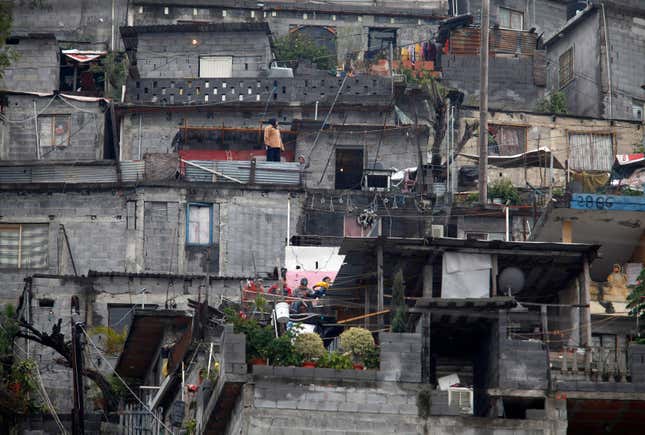

The state’s per-capita income, however, has tumbled in roughly the same period, according to the Mexican agency that monitors poverty, Coneval, and the percentage of people who can’t afford a basic basket of goods has risen (Spanish), though both measures have improved slightly since 2014.

As a sign of this, Mexico’s Nafta showcase is still fertile ground for shanty towns. I visited a relatively new one. The residents, migrants from the southern state of Oaxaca, had assembled a lane of shacks, their makeshift courtyards perfumed with plants from back home. A dusty donkey stood nearby, tied to a shrub. Just a few years ago, these people would have continued north to the US. Nuevo León’s robust economy now offers them a way to make a living, if not a good one. For now, all the government provides are periodic water deliveries.

Bad air

Much of that kind of haphazard development is tucked away out of sight, but there’s one consequence of the city’s unruly administration that everyone in town, rich or poor, can experience: the air. Because house prices have climbed so much, Monterrey’s growing workforce has been forced to move farther and farther away from the city’s core. They now ride in and out every day in worsening traffic.

On a recent afternoon, Monterrey’s chiseled mountains—the only defining feature in what is otherwise a nondescript city—looked blurry behind a thick haze from the 27th floor of the state government’s office tower. “I can measure pollution from here,” joked Alfonso Martínez, the state’s head of environmental protection.

The fact that Martínez, a scientist who was part of a citizen watchdog group fighting for better air quality, now occupies that office is a promising sign. “El Bronco,” the state governor, whose real name is Jaime Rodríguez, was elected in 2015 on the back of frustration over corruption. Since he took office, there’s been a big push to clean up the city’s air by raising public awareness and writing rules to keep industry in check, says Martínez. He believes those and other changes will eventually lift the haze from Monterrey’s scenic hills.

If, that is, Nuevo León’s residents don’t revolt before then. Rodríguez’s approval ratings are even lower than Trump’s. Only one third of the state’s residents approve of the job he’s done so far, according to a January poll by Consulta Mitofsky. After security, their top worry is the economy.

It doesn’t sound that different from Trump voters’ concerns, and it’s not hard to imagine how the kind of working-class rebellion that helped propel Trump to the White House could engulf Monterrey as well. But unlike Trump supporters, regios are so far holding on to the historic openness that set their city on a path to globalization more than a hundred years ago. More than geographic location, a good education system, or cheap wages, it’s that international mindset that seems most essential for communities to stand a chance—never mind win—in a globalized economy.