US president Donald J. Trump has won preliminary approval to register three dozen new trademarks in China covering everything from bars and hotels to child-care and massage services, raising further concerns over potential conflicts of interest.

The Chinese government has granted preliminary approval to 35 new Trump trademarks, according to two documents published by China’s Trademark Office in recent weeks. The Associated Press first reported on the registration status.

Trump’s lawyers applied for a trove of new trademarks in China last April, as Trump bashed China for currency manipulation and stealing American jobs during his electoral campaign. The Chinese trademark office gave preliminary approvals for nine of the marks on Feb. 27 and for another 26 on March 6, according to Quartz’s examination of registration information published via the agency’s website. It rejected seven.

The 35 trademarks will go into effect after three months, if no one objects. Since 2005, Trump has filed for 126 trademarks in China for his business empire, and as recently as June 2016, his lawyers applied for three new marks in clothing and footwear, which are still under examination. Trump already has 77 trademarks in effect in China, while four were earlier rejected.

Of the 112 trademarks formally registered or pre-approved, more than half of them use “Trump” or “Donald Trump,” and their Chinese translations. Those include two different translations of Trump’s surname—川普, or 特朗普. (Here’s what they sound like.)

They mainly focus on industries that include finance, construction, entertainment and advertising, while a few relate to less predictable areas like photographic equipment and luggage.

In China, a registered trademark is initially valid for 10 years. Most of Trump’s 77 marks in use will be up for renewal in the last year of his term, in 2020.

Special treatment?

The question at the heart of Trump’s latest rounds of trademark approvals is whether the US president has received any special treatment from the Chinese government, and if so whether that would reach the level of a violation of the “emoluments clause,” of the constitution. The clause bars someone who holds office in the US from receiving gifts or fees from a foreign state without the consent of Congress. Some legal experts have noted that they’ve never seen so many trademarks being approved by Chinese authorities in such a short period of time. But the suggestion of special treatment has been disputed by China’s foreign ministry and Trump’s business associates, as well as China-focused IP lawyers. Instead, he may have benefited from reforms China has made to its trademark law in recent years.

Article 28 of China’s trademark law (pdf, p.9) states that the trademark office shall complete the examination of a trademark registration application within nine months from the filing date. In Trump’s case, it took about 11 months. Chinese IP lawyers say Trump’s examination time is not an outlier from that seen in other applications.

“The same publication pages show marks filed by other applicants around the same time,” said Hu Mimiao, an IP lawyer with Orrick in Beijing, referring to the official documents on Trump’s trademark approvals. She added that some cases in the documents did take longer to review, but that’s because they were preliminarily refused, she said, “and then applicants overcome the refusal through subsequent administrative review or even court appeal proceedings.”

Trump’s IP interests in China first raised eyebrows when he obtained a trademark for construction services this February, after a pre-approval for the mark from the Chinese government in November. The decision overturned previous court rulings (link in Chinese) in favor of a Chinese man named Dong Wei, who had registered the “TRUMP” mark for construction services in 2006.

But Dong still owns the right to use “TRUMP” for mining and drilling services, which are included in the broad classification of construction services in international IP standards, according to an earlier decision from the trademark office’s review board. As Matthew Dresden, an IP lawyer with Harris Bricken in Seattle, noted in this blog post, that’s because Trump, presumably, was unable to show that he is well-known for those two services in China. Bricken noted that Trump’s case, as well as a similar case that involved Michael Jordan, are only “partial victories” when it comes to foreigners protecting their name rights in China.

Still, lots of copycats

It’s not unusual for Western brands to come up against unexpected IP challenges in China—and lose. Here’s a roundup of the most recent China vs. foreign trademark disputes, which show mixed results.

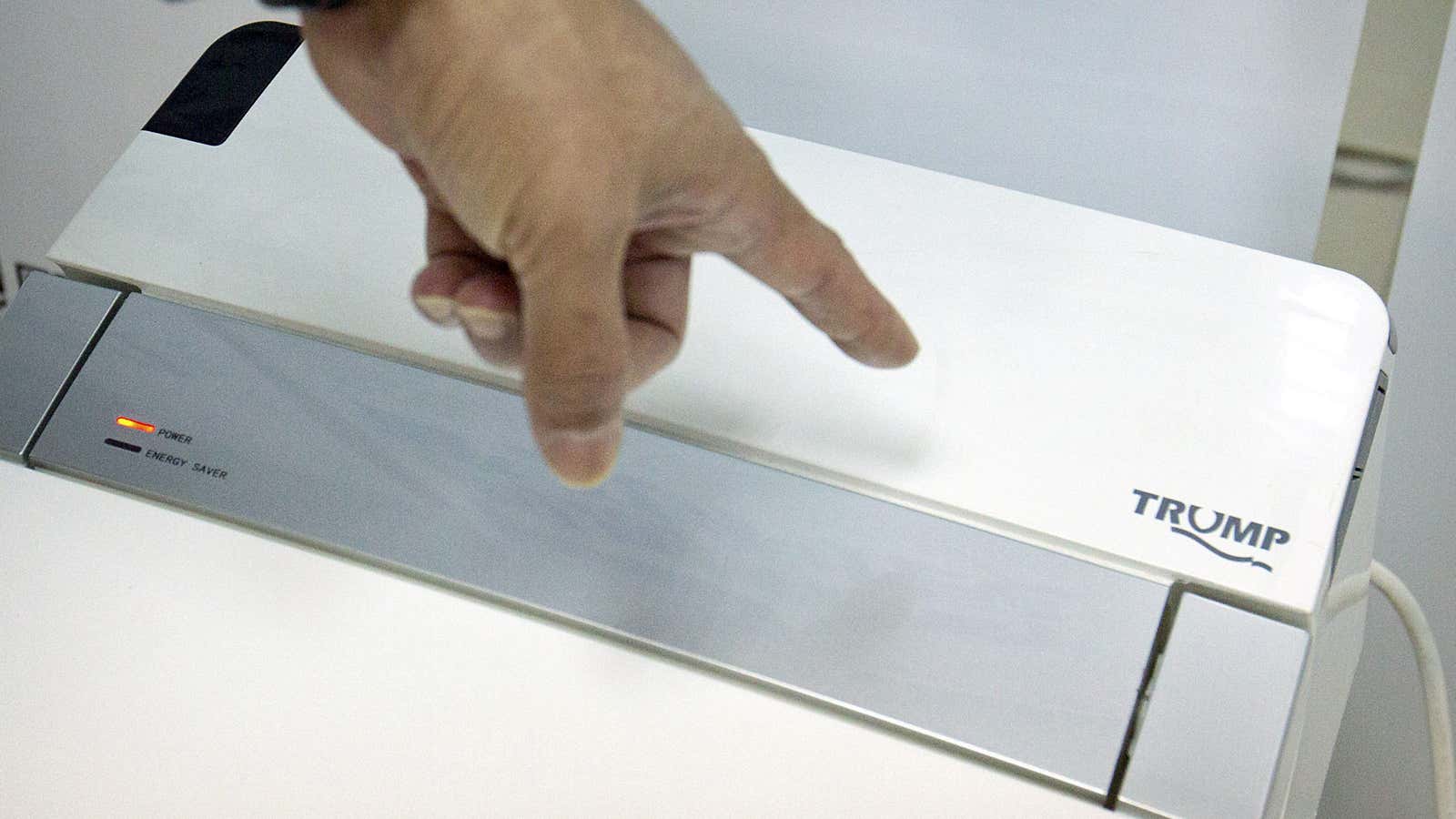

Trump’s names have appeared in China on everything from toilets that can offer pregnancy tests to condoms to pacemakers—without his permission. The founder of a Chinese high-tech toilet brand called “Trump” said in a recent interview with the New York Times that he had never heard of the name of the American property mogul when he registered his name as a trademark in 2002.

A search of “川普” on the trademark office’s website leads to 169 results, of which only 35 are trademarks owned by Trump. Of course, it’s true that “川普” can carry some general meanings in Chinese, but it’s almost certain that many of those applicants ripped off the US president’s name intentionally. For example, a farm product sales firm in Chongqing applied to use the name of “川普老爹” (which means Daddy Trump) to sell fruits and nuts, two days after Trump won the election, while another applicant from central Henan province went with “川普大叔” (which means Uncle Trump) for tea, honey and candies almost around the same time. Both applications are now pending under review.

It is difficult for Trump to sue people who have already managed to register his name as trademarks in China, particularly those not related to his core real-estate businesses, as Trump has to prove that his name was already famous in China in those areas at the time the application was filed. In any case, it’s possible that Trump doesn’t intend to turn his latest batch of trademarks into real businesses in China, but instead hopes to prevent others from stealing his name for profit. Trump’s legal representative in China has previously said that she encourages such a “defensive strategy.”