Nick Hayek wants Swatch to roll out its own smartwatch OS rather than use Android Wear. This is a grave mistake that shows little understanding of smartwatch success factors and of competitive software engineering cultures and their ecosystems.

Lebanese-born and Europe-schooled, Nicolas Hayek père was a genius.

In 1983, two venerable but mortally ailing Swiss watch industry companies, ASUAG and SSIH, called Hayek to their bedside to perform the last rites and liquidations. The companies had been unable to withstand competition from Japanese quartz watch manufacturers such as Seiko, Casio, and Citizen. It was the humane thing to do.

But rather than pull the plug, Hayek demonstrated his unique combination of management, technology, and marketing savvy by making a counter-intuitive decision: In the middle of the “quartz crisis,” Hayek refused to give up on traditional mechanical designs. He merged the two entities and adopted a project from subsidiary ETA SA, whose CEO, Ernst Thomke, and two engineers, Elmar Mock and Jacques Müller, had come up with a simplified mechanical design that used only 51 pieces when 150 was considered the minimum.

Thus the Swatch was born.

Hayek found investors for the merged company, placed himself at the helm, took the new company private, and, in 1986, renamed it Société de Microélectronique et d’Horlogerie (SMH).

SMH wasn’t just a company, it was a Swiss federation of parts manufacturers, component engineers, watch assembly companies, and brand organizations (Omega, Blancpain, Bréguet). Under Hayek’s leadership, the conglomerate arose from its sickbed and manufactured the Swatch in numbers that repelled the Japanese invasion. A less precise mechanical watch had beaten the ultra-precise quartz time pieces.

Swatches were fun, inexpensive, European, and fashionable. They were a kind of costume jewelry that was constantly iterated, they possessed the soul that the Japanese watches lacked. Showing a keen understanding of his wide range of customers, Hayek also revived articles of mechanical pride such as the delightfully complicated Bréguet wristwatches.

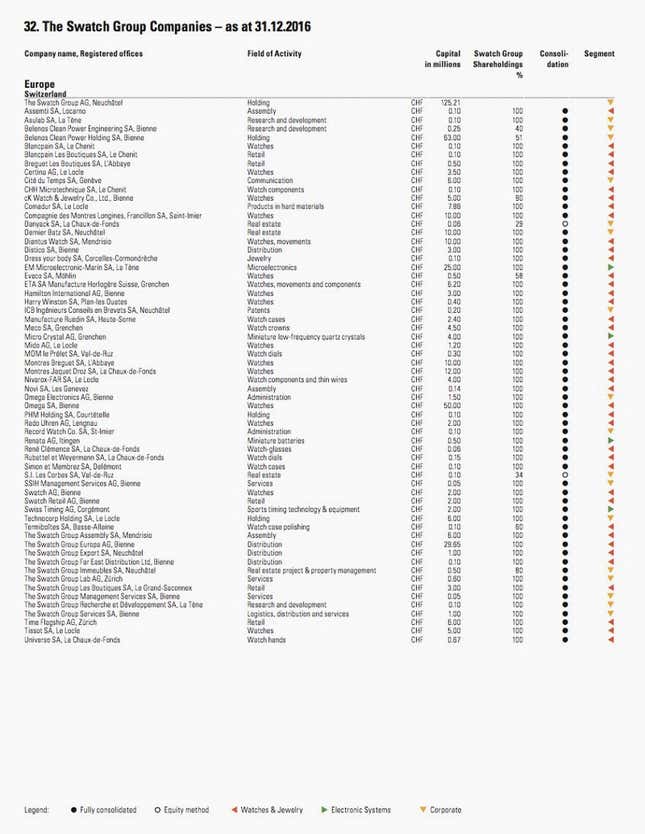

Such was the impact of the simplified mechanical watch in the conglomerate’s success that, in 1998, SMH was renamed Swatch Group. It is now a federation of more than 70 companies:

I had the opportunity to meet Nicolas Hayek in the late nineties. Energetic and hard-spoken, he proudly wore two watches, one of which the original Swatch with its blue plastic band. He passed away in 2010 at the age of 82.

The Hayek family has maintained bloodline control of the Swatch dynasty. His daughter Nayla chairs the Swatch AG Board, his son Georges Nicolas (a.k.a. Nick) is the CEO, and grandson Marc is also on the Extended Group Management Board and CEO of Jaquet Droz and other group brands.

But succeeding a man such as Nicholas Hayek isn’t easy. This was never more apparent than when, in 2013, Hayek fils publicly pooh-poohed smart watches:

Personally, I don’t believe it’s the next revolution…Replacing an iPhone with an interactive terminal on your wrist is difficult. You can’t have an immense display.

(A contemporaneous and not entirely laudatory Monday Note comment can be found here.)

His skepticism may have stemmed from Swatch’s short-lived flirtation with Microsoft’s SPOT (Smart Personal Objects Technology) platform in 2004–2005. The SPOT-powered Swatches quickly disappeared with the platform.

Much has happened since Nick Hayek’s infelicitous words.

On Sept. 9, 2014, Apple unveiled its smartwatch. The global span of the event and imprimatur of fashion world luminaries created heightened expectations. But Apple’s diffident refusal to release unit and revenue numbers after the device started shipping in April 2015 provoked critics to label the Apple Watch a disappointment, even as competing smartwatches weren’t doing so well.

In Sept. 2016, the Watch Series 2 was announced, concurrent with improvements and a price reduction for the earlier model (now starting at $269). Perhaps more important, the fashion and luxury angles were replaced by an accent on health and fitness, highlighted by the Apple Watch Nike+.

Apple still refuses to release Watch numbers, but the device is estimated to have had a successful Holidays quarter. The Canalys research firm (all caveats hereby stipulated) pegs unit sales at six million for the quarter with a revenue of $2.6 billion—that’s 80% of the total smartwatch market. Apple CEO Tim Cook, known for the reliability of his public statements, calls sales growth “off the charts.” If the numbers are accurate, Apple has become the second largest watchmaker by revenue, right behind Rolex.

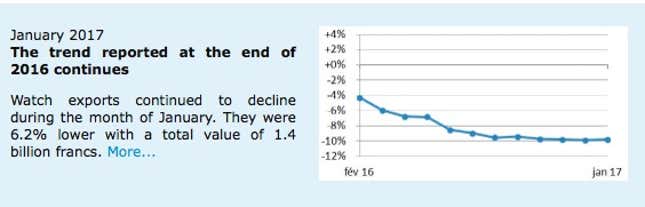

In the meantime, the Swiss watch industry continues its decline (from the very precise Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry (FH)):

A look at the 2016 annual report for the Swatch Group shows an even more accentuated revenue decline; they lost 10.6% last year:

This leads us to Nick Hayek’s latest pronouncement: In collaboration with with renowned Swiss research institute CSEM, Swatch will write its own smartwatch OS [as always, edits and emphasis are mine]:

[CSEM and Swatch are working to] launch an ecosystem for connected objects by the end of 2018 [that will] offer absolute data protection and ultra-low energy consumption and [will] not need regular updates.

Hmmm…

Allow me to play angel’s advocate for a moment and imagine what Nick Hayek sees and wants to achieve. The ultra-low energy consumption part might be connected to the recent CSEM announcement of the world’s smallest Bluetooth chip (5M transistors on a 5mm2 chip) that they created in collaboration with the Swatch Group:

It is—first and foremost—the smallest Bluetooth chip on the market. The ultra-miniaturization of electronic components is crucial for the densification of functions in portable electronic devices and for the Internet of Things.

It has the lowest energy consumption—compared to its competitors—for different scenarios of use, thus increasing the autonomy of connected objects, an essential factor in this field.

Its high-speed start-up capability is unparalleled, which makes it possible to improve the reactivity and the lifetime of, for example, electronic beacons.

Indeed, extremely low power Bluetooth connections would open up a universe of opportunities for connected objects.

But I have to return to form and wonder about the wisdom of the SwatchOS project.

First, we have to question this umpteenth evocation of a bright Internet of Thins (IoT) future. The competing cries for openness and privacy demand the participation of strong ecosystem players—companies that are able to (slowly) grow and enforce standards that are technically competent and secure. Does Swatch have the resources to be a leader in this cause? Swatch Group net 2016 sales were about $7.5 billion, net income a modest 7.9% of sales, and its cash position about $1.1 billion. (I’ve used a 1 CHF = $1 exchange rate.)

Second, anybody can write an operating system (yeah, I know…), but it’s a much more difficult task when the creator declares that the OS won’t need regular updates. This is extremely bizarre. What about bugs fixes, security updates, more/better functionality?

Third, what about third-party applications? Creating an operating system is one thing; building an ecosystem of developers around it is a much more difficult task. Does Swatch assume there won’t be any third-party apps, that only Swatch can write code for Smart Swatches?

Lastly, the “end of 2018” time frame. Assuming the project stays on schedule (it always does, of course), Apple will have launched two new Watch models and countless watchOS updates by the 2018 Holiday quarter. Android Wear will also go through major iterations with its hardware partners.

Nick Hayek’s father triumphed against Japanese quartz watch makers by playing on his own turf. Trying to defeat the established smartwatch players by playing their game won’t work. Is there something in Swatch Group’s culture that predisposes it to be competitive with Google and Apple software engineers?

Just as Nokia should have embraced Android in 2010, riding on its proven combination of design, supply chain, and carrier distribution prowess to keep a leading role in the smartphone revolution, Swatch could use its native—but circumscribed—cultural and technical skills to create beautiful, fun smartwatches…that run on Google’s software. But just like Nokia’s culture and success prevented it from seizing the Android moment, similar factors will keep Swatch from being a powerful player in the smartwatch world.