In the United States, the number of books translated into English is low: roughly 3% for fiction and poetry (although that may be improving). In children’s literature, it’s even more minuscule. American parents, it seems, aren’t keen on buying their kids books with unfamiliar settings and experiences, and publishers aren’t jumping to spend the money to bring them over.

“Remember that in a lot of children’s literature, the parent is the consumer,” says Porter Anderson, editor and chief executive of Publishing Perspectives, which focuses on international publishing. “While some parents may want to open their kids’ minds to an international sense–particularly in this time of deeply disturbing nationalism in many parts of the world–others simply aren’t as comfortable with this.”

Despite US president Donald Trump’s promotion of “America First,” we here at Quartz believe the future is more multicultural than the past, and that a world with lower borders is one worth working toward. To that end, there’s a danger in telling children stories with just one worldview.

When author Chimamanda Ngozie Adiche realized that American and British children didn’t have a monopoly on the childhood story, her perception of the world changed. As she says in “The danger of a single story,” “I realized that people like me, girls with skin the color of chocolate, whose kinky hair could not form ponytails, could also exist in literature.”

So there’s power in difference. But so too is there power in discovering what makes us similar. Kids all over the world are concerned with counting, getting lost, imitating animals, making friends, and dealing with new family members, and those commonalities connect us across borders. Indeed, the best kids’ books work around cultural barriers by including characters who are stripped of identity and gender—they’re animals, shapes, or alien forms—so that any kid can imagine themselves in the story.

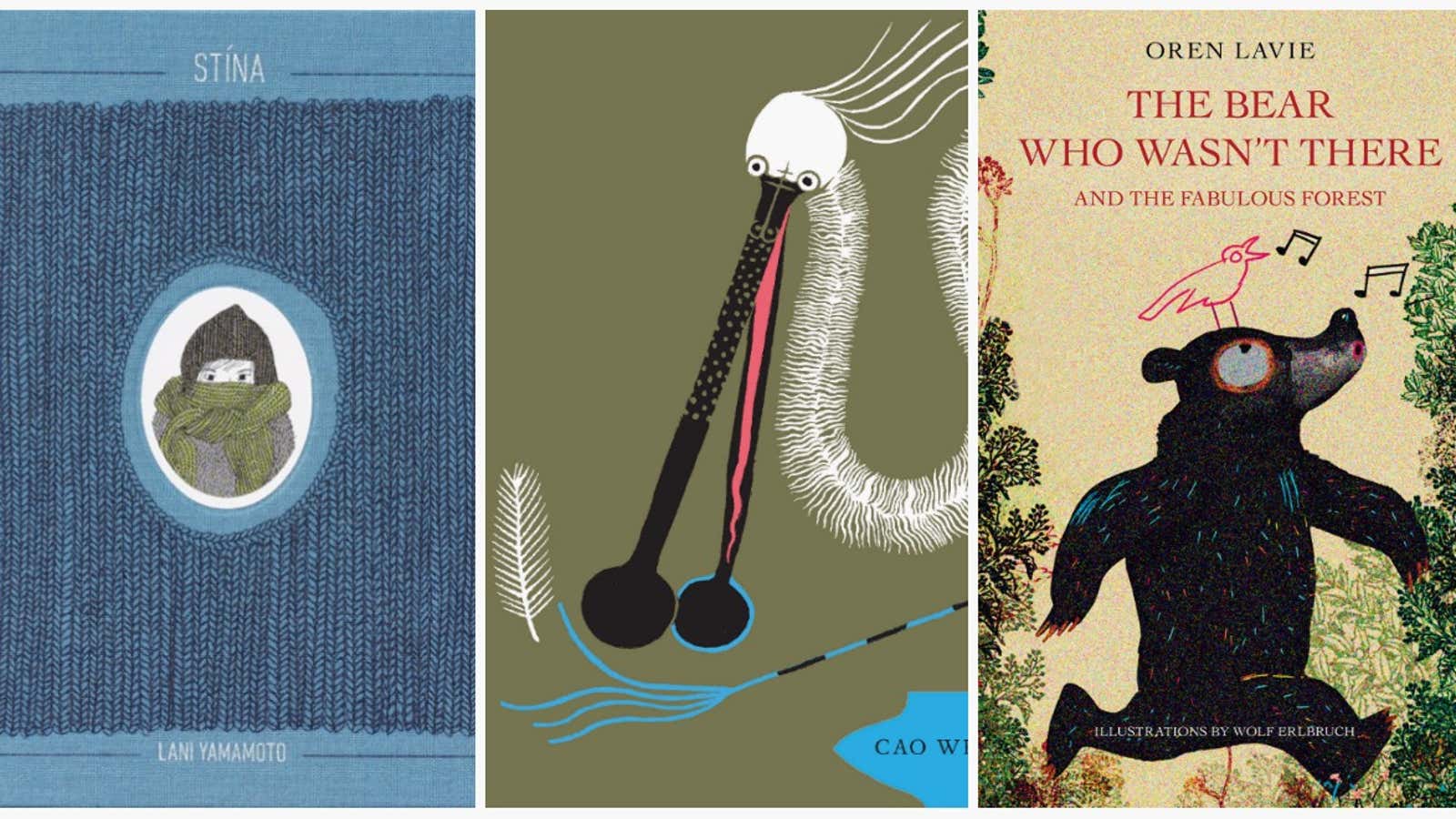

Beyond the European classics of Babar, Tintin, and The Little Prince, here are some of the best contemporary picture books translated into English:

Denmark

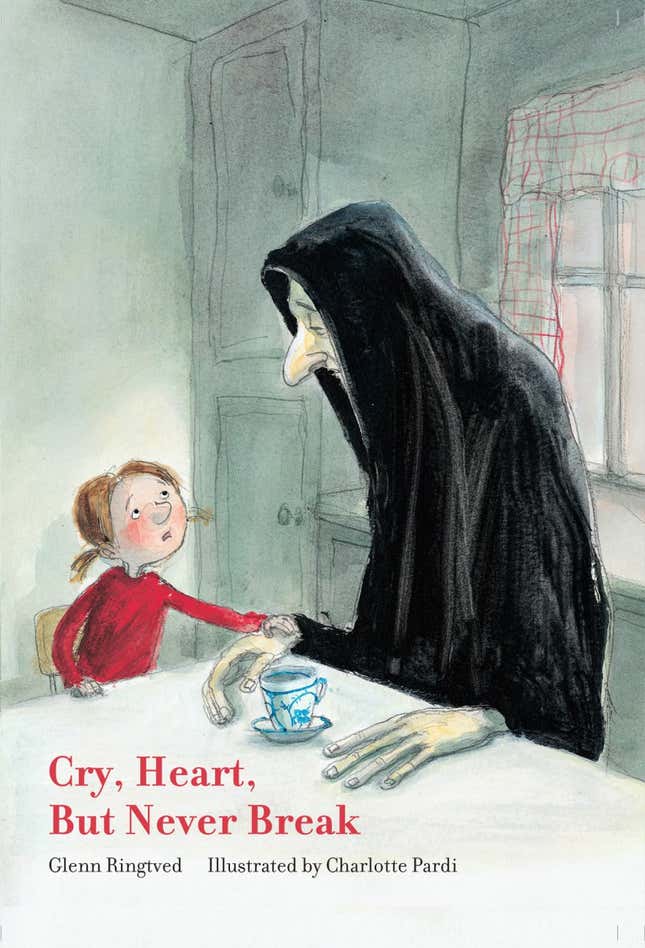

Cry, Heart, But Never Break, by Glenn Ringtved, illustrated by Charlotte Pardi, translated by Robert Moulthrop

In this gloomy book, four children get a visit from a tall cloaked Death, who arrives for tea as their grandmother is dying upstairs in their house. Ringtved refrains from glossing over reality with euphemism, and the despondent people gathered around a table as their loved one dies nearby may look miserably familiar to adult readers.

Japan

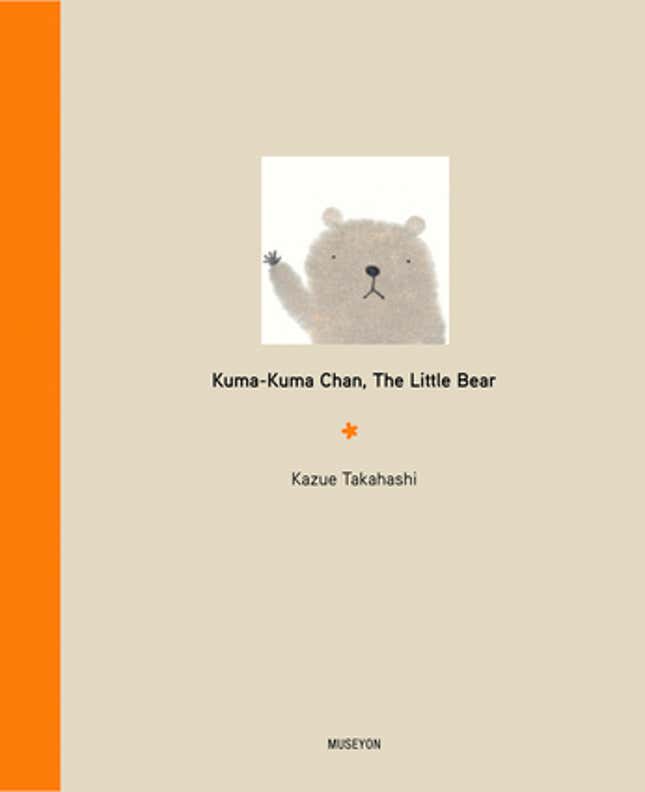

Kuma-Kuma Chan, The Little Bear, by Kazue Takahashi

In this book of simple drawings, lone bear Kuma-Kuma Chan does lone-bear things: He naps, makes salad, cuts his fingernails, and looks at the clippings. Written and illustrated by Takahashi, the book is the first in a series about Kuma-Kuma, who loves to sit at the top of mountains, drink coffee and “listen…to stars.” The lone bear is a hero for all introverted, self-entertaining children.

Iceland

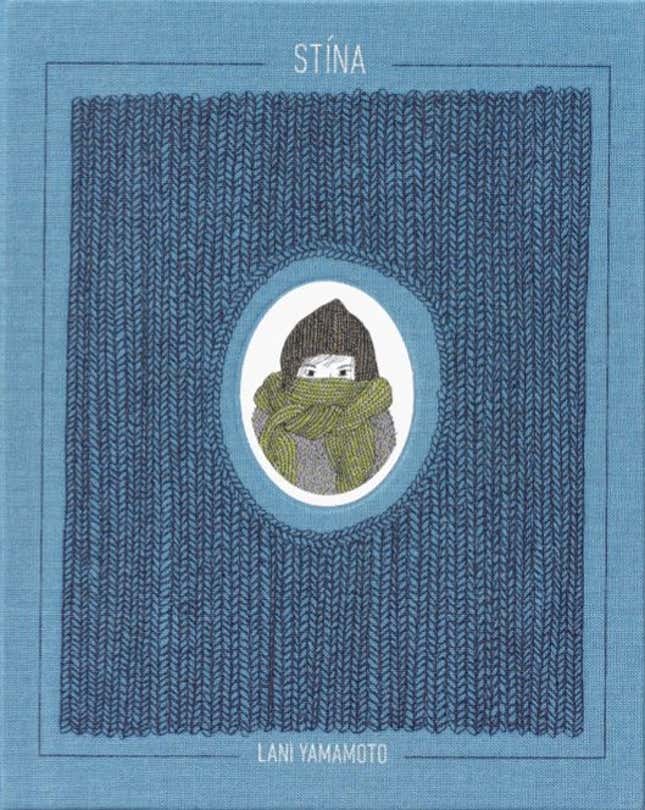

Stina, by Lani Yamamoto

In Stina, the titular heroine battles the cold. She huddles inside, knitting herself a protective duvet-cave, until one day two children bust into her house, warm from playing outside, and she has to rethink her isolation. Yamamoto, a transplant to Iceland from Boston, translated the book herself after it was originally published in Icelandic. A lovely story for teaching kids ingenuity, inner courage, and the joy of knitting.

Germany

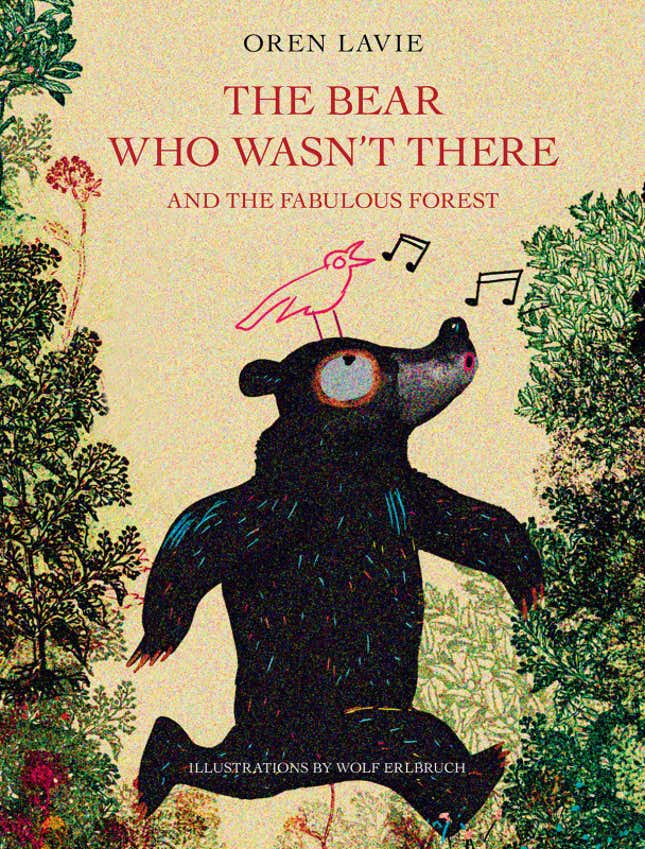

The Bear Who Wasn’t There, by Oren Lavie, illustrated by Wolf Erlbruch

In the sumptuously illustrated Bear Who Wasn’t There, a bear faces a Lewis Caroll-flavored crisis: He has forgotten who, and what, he is. Piecing himself back together, the bear wanders the forest and meets Convenience Cow and Penultimate Penguin. The story was originally written in English by Israeli musician Oren Lavie, but was published first in German. It enjoyed a multilingual journey—with editions in Italian, French, and Dutch, among others—before it came to English readers.

Brazil

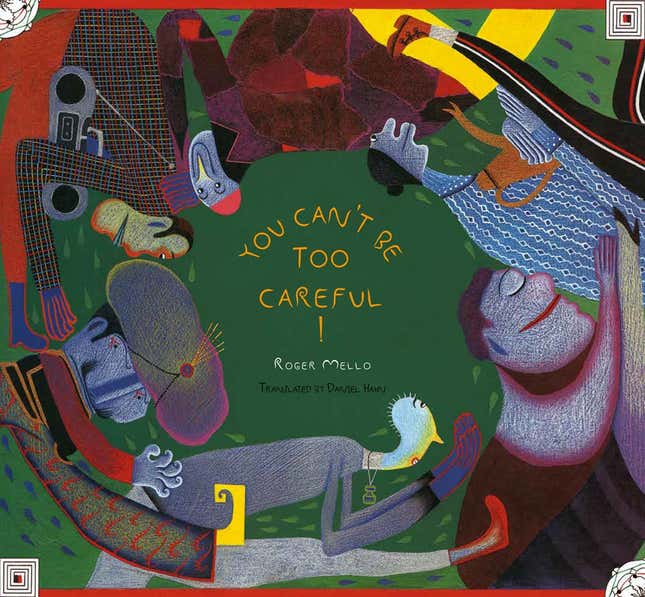

You Can’t Be Too Careful! by Roger Mello, translated by Daniel Hahn

Complex and dizzying, You Can’t Be Too Careful! features a vast set of characters whose actions and inactions are all tightly knit together. The book is a dramatic lesson in logic and consequence. A love letter gets lost because of a man’s ridiculous mustache; a man who’s on the verge of death lives—because his monkey ran away from the circus, because the world fell on the floor. See what I mean?

Tanzania

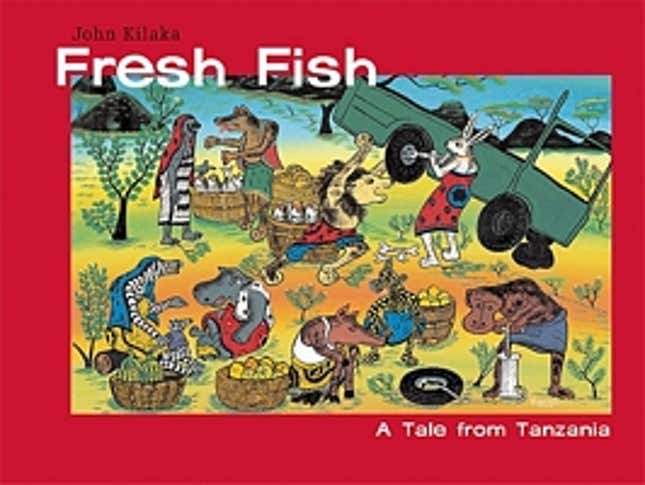

Fresh Fish, by John Kilaka

In Fresh Fish, Sokwe, a chimpanzee, encounters the shifty Dog, who is trying desperately to pilfer fresh-caught fish from his friend. Patterned animals, drawn in the Tanzanian Tingatinga painting style, dance and party, and Dog is put on trial. The book was first published in German in Switzerland, before it was translated into English.

France

Press Here, by Hervé Tullet

This interactive book’s bare pages contain yellow, red, and blue dots that “change” when you press them or when you shake the book. Press Here has been massively popular since it came to the US in 2011, and has delighted children across the world.

China

Feather, by Cao Wenxuan, illustrated by Roger Mello, translated by Chloe Garcia Roberts

In this picture book, Feather is a feather. It wanders the earth, blown by the wind, and wonders where it came from. As Feather encounters different kinds of birds, it asks, “Am I yours?” The beautifully detailed illustrations, by the author of You Can’t Be Too Careful!, accompany Feather on its disheartening journey to a violent climax. The book comes out in September in the US, but it’s worth the wait.

Mexico

Salsa, by Jorge Argueta, illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh, translated by Elisa Amado

A bilingual book, Salsa is another in a series of “cooking poems” by Argueta. Flat, earth-colored illustrations show a brother and sister learning about the history of salsa and how to make it, while using cilantro and tomatoes like musical instruments in their edible orchestra.

Iran

The Little Black Fish, by Samad Behrangi, illustrated by Farshid Mesghali, translated by Azita Rassi

In this new translation of Behrangi’s beloved 1968 Persian book, a small black fish finds the meaning of freedom in a vast and exciting—but dangerous—sea. The fish leaves his family in his tiny pool to explore, and meets powers much greater than him. The book was considered a political allegory at the time it came out, and was reportedly banned in pre-revolutionary Iran.