It’s a strange time for Japan to commemorate its post-Second World War pacifist constitution, which turns 70 today (May 3).

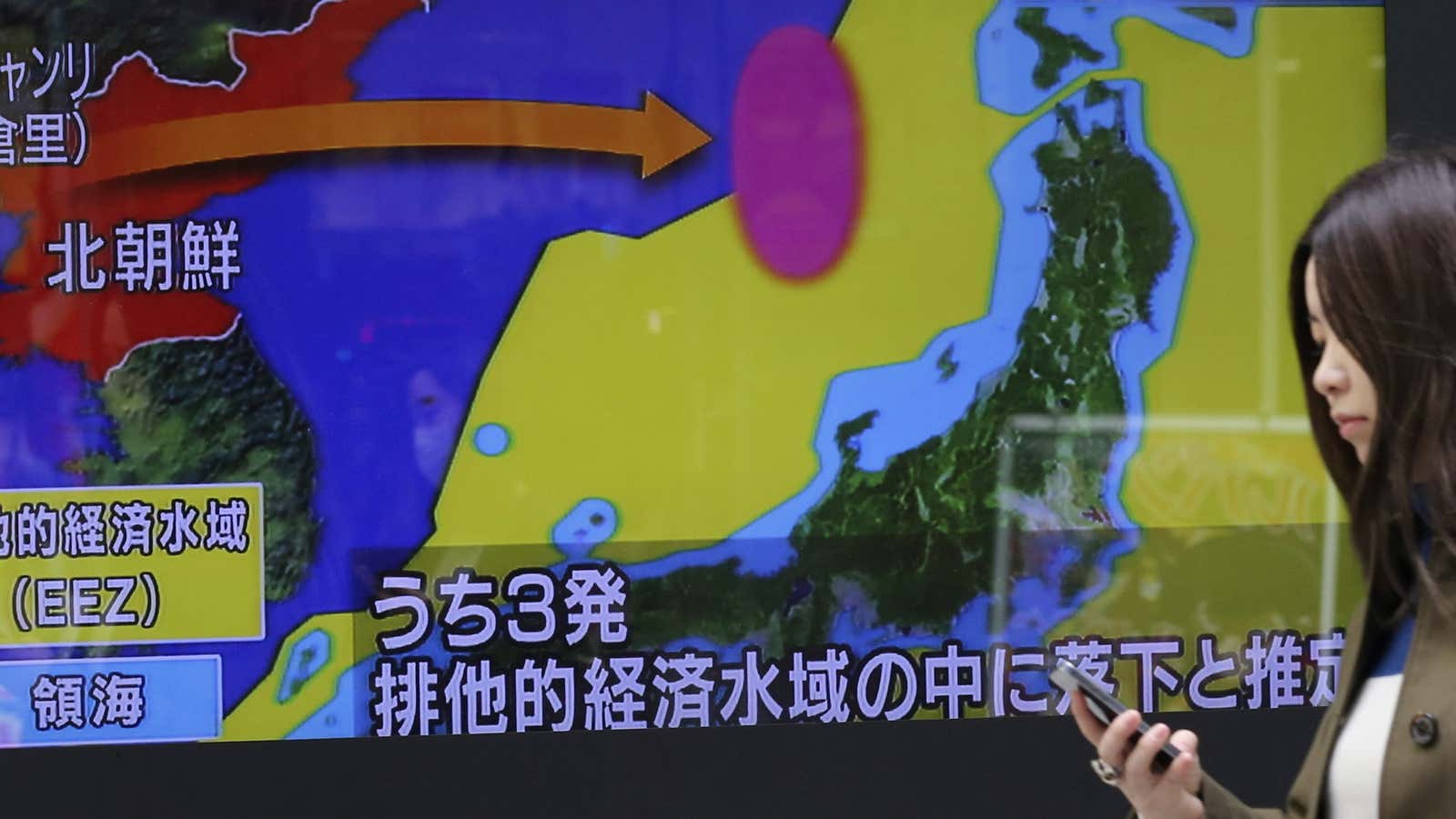

This week, Tokyo’s subway system was briefly halted as North Korea test fired a missile. Schools in one prefecture have sent letters to parents warning them of the potential threat of ballistic missiles. And the Japanese government is mulling evacuation plans (paywall) of Japanese citizens from South Korea in case of an emergency.

All this raises the question of whether it’s time for Japan to rethink its constitution, in particular Article 9 of the document, which forbids Japan from using military force for offensive purposes, an atonement for its wartime aggression. Reforming the constitution is a long-held dream of prime minister Shinzo Abe—who is the grandchild of Nobosuke Kishi (paywall), a former prime minister who was accused of war crimes and dreamed of remilitarizing Japan.

“We will without fail take a historic step toward the goal of changing the constitution in this anniversary year,” Abe said on Monday (May 1).

Some recent polling might give Abe a shot in the arm. According to a poll conducted by Kyodo News agency and released on April 29, 49% of respondents said that Article 9 must be revised, compared to 47% who opposed changing it. A previous poll conducted by Kyodo in October found that 45% supported a revision, while 49% of people didn’t see a need to revise Article 9. In another poll (link in Japanese) released yesterday (May 2) by the left-leaning Asahi newspaper, 63% said they didn’t want to amend Article 9, down from 68% last year, while those agreeing with a revision increased to 29% from 27%.

Japan enacted its current constitution in 1947, after its surrender in the Second World War. Many conservatives in Japan decry that the constitution was forced upon the country by occupying US forces. Supporters of the constitution believe that it has allowed Japan’s economy to develop under the umbrella of America’s protection, and also prevents Japan from being drawn into another war. Instead of a “proper” military, Japan has a Self-Defense Force (SDF), while a treaty with the US promises defense from adversaries.

Some have accused Abe of drumming up hysteria over the threat from North Korea to further his own political agenda—a tactic that, if true, seems to be working, judging by persistently high public support for Abe’s cabinet. Toshio Tamogami, a SDF general known for his nationalist views, said in a tweet (link in Japanese) that the closure of the Tokyo subway was an overreaction. South Korea’s government also said that Abe’s government is exacerbating tensions on the Korean peninsula.

There is also concern that the SDF has become less “defensive” over the years. Members of the SDF recently served in a United Nations peacekeeping mission in South Sudan, but the mission was recently called off in part due to criticism that Abe was using it as an opportunity to expand Japan’s military role overseas. Abe has also refused to cap military spending at 1% of GDP. This week, Japan said it would send its biggest warship to escort a US supply ship, the first such operation conducted by the SDF during peacetime, and one made possible by legislation that was passed (paywall) in 2015 allowing the SDF to take part in combat missions overseas.

For now, Japan remains constrained to be pacifist not just because of its constitution, but because of a military that, while one of the most sophisticated in Asia, lacks offensive weapons and pilots who could fly F-15 fighter jets loaded with bombs into North Korea. Ultimately, Japan must rely on Article 5 of its constitution, which stipulates that the US comes to Japan’s defense.

And even with a two-thirds majority in both houses of Japan’s Diet, Abe’s goal still seems out of reach. His party is in a coalition with the Komeito—a small party linked to a Buddhist sect that advocates pacifist principles—which could act as a brake on Abe’s aspirations. Should Abe decide to call a general election this year while the opposition lies in tatters, constitutional revision isn’t an issue that “voters are particularly keen on” as past elections have shown, said Ian Neary, a professor in Japanese politics at Oxford University. “What most voters are much more concerned about is the economy and whether Abenomics is working.”