Last week, the US Federal Reserve roiled markets with the suggestion that it plans to slow its program of quantitative easing—the flood of bond purchases intended to hold down long-term rates and boost the economy—sometime toward the end of 2013. But the so-called “taper” of QE may be further off than markets believe.

Yesterday the researchers who measure economic activity for the US government delivered a final reading on GDP growth for the first quarter of this year. Rather than the sunny 2.4% annualized growth that had previously been reported, the figure is 1.8%. The changes came largely from over-estimating consumer spending on services, which was likely lower due to tax increases at the start of the year, and lower exports, perhaps attributable to a strengthening dollar.

The Fed and its chairman, Ben Bernanke, last week made it clear that bond-buying will only slow if the economy continues to improve as the central bank had forecast: namely, at 2.3%-2.6% growth and less than 7% unemployment. Even at the time, some thought that premature. For instance, James Bullard, a member of the Fed’s board who dissented from last week’s Fed policy statement, argued that the bank had tailored its forecast of coming conditions to ensure that QE would start to wind down this year.

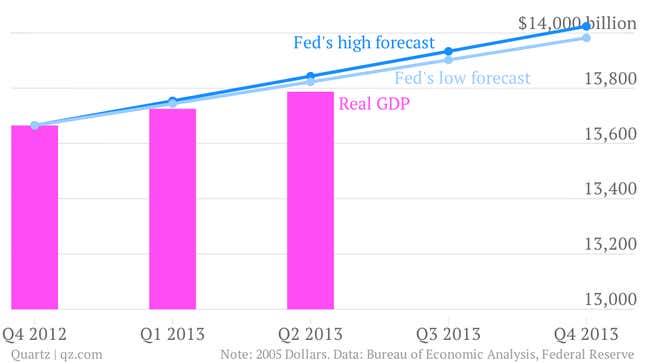

Today’s revised growth figure suggests that even after Bernanke downgraded the Fed’s typically optimistic growth expectations—which he did at last week’s meeting—they’re still too high:

The chart above was inspired by an analysis at Calculated Risk, which notes that economic growth, unemployment, and inflation are all likely to fall short of the Fed’s expectations. In the past this has led to the extension, not the reduction, of “unconventional” monetary policy such as QE.

So if the central bank’s decisions are as data-based as it officially assures us, growth is going to have to accelerate quite a bit for the rest of this year for the tapering of QE to begin as early as, say, September (which is the date some think the Fed’s members had in mind). Otherwise, Bernanke will have to do a lot of explaining to convince markets, and his own board members, that monetary policy isn’t being set to the calendar.