To save itself, Uber is ready to throw its star engineer under the bus

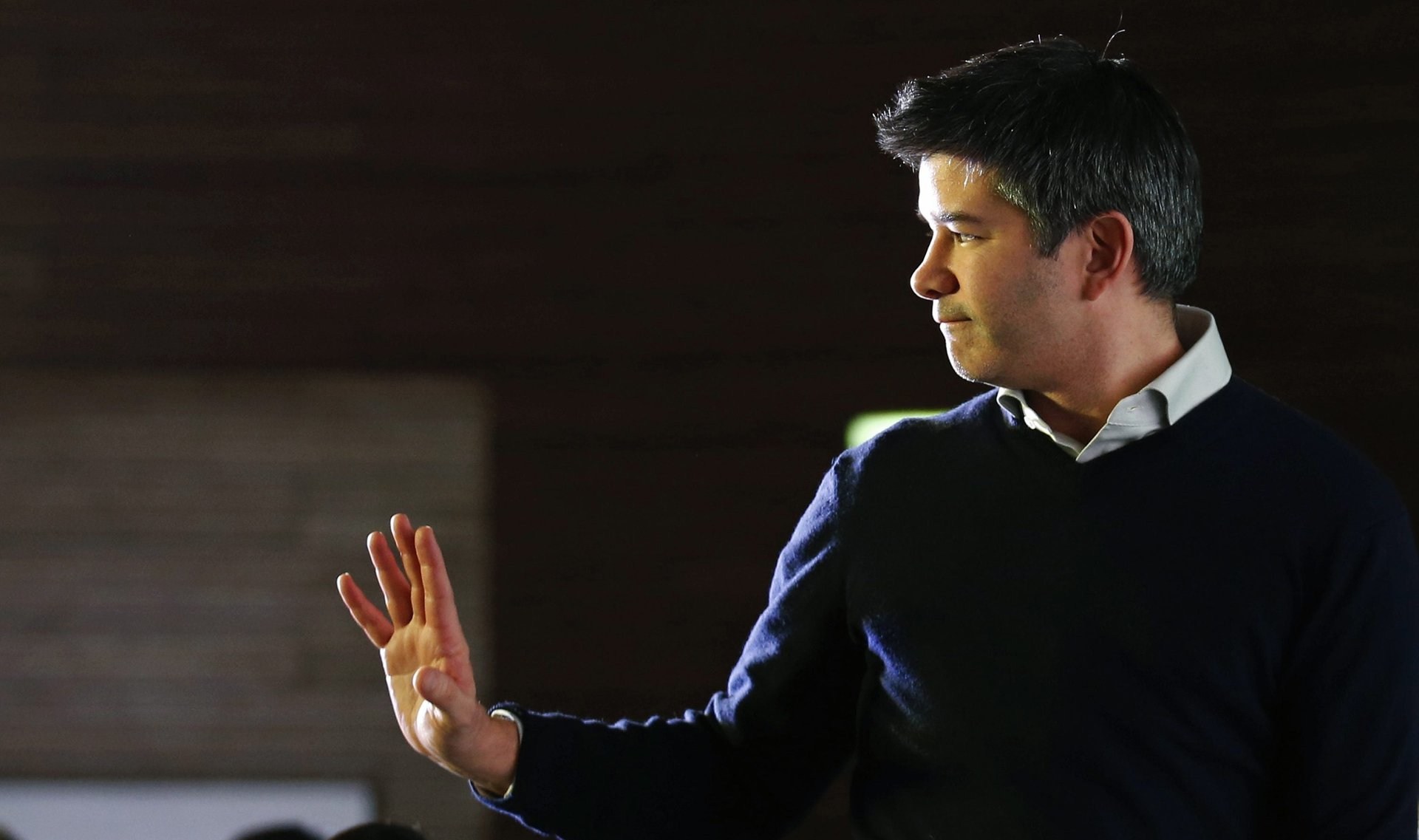

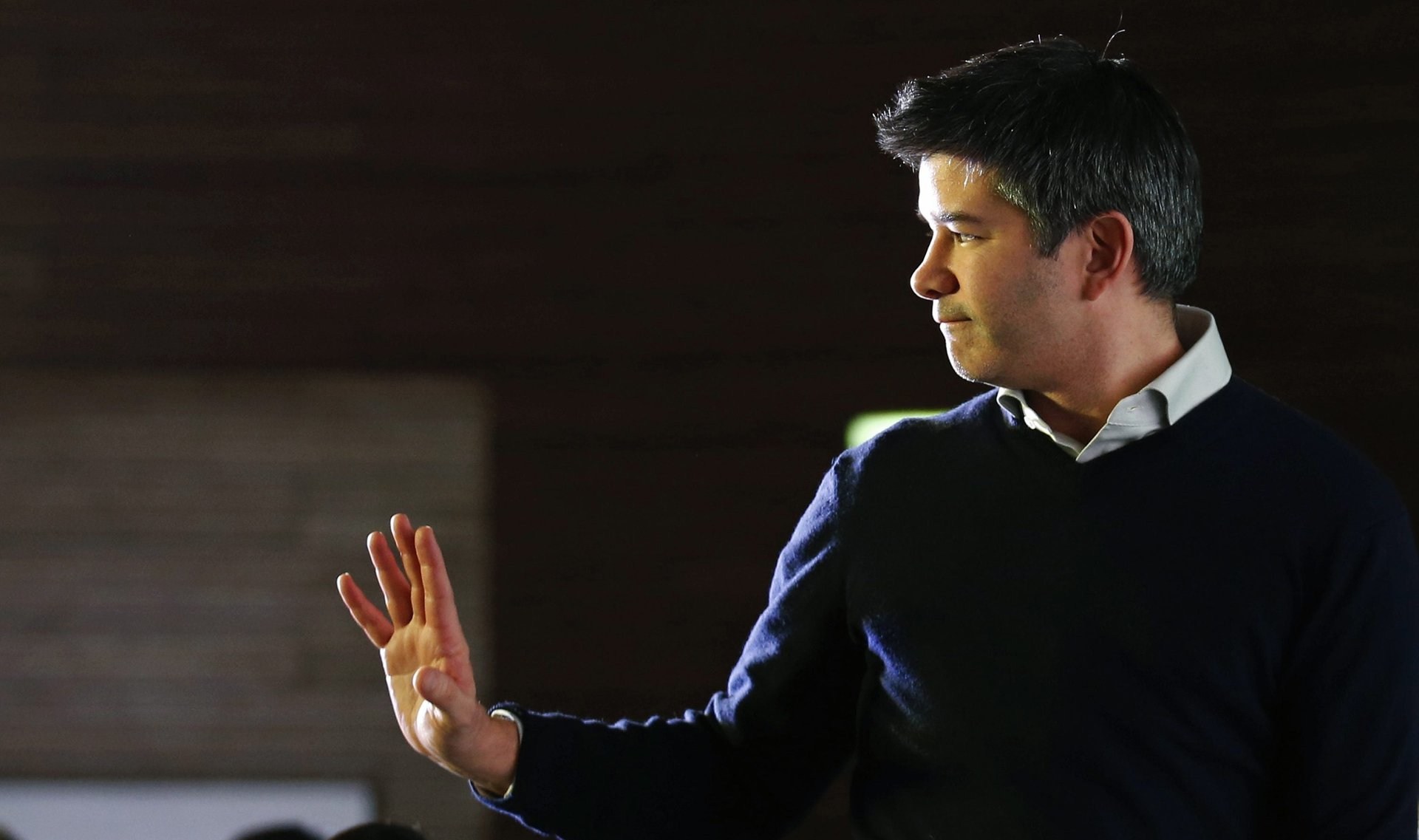

Uber paid $680 million to make Anthony Levandowski the head of its self-driving car program. The ride-hailing juggernaut acquired his driverless trucking startup, Otto, with its small team of ex-Waymo engineers and proprietary lidar technology, in August 2016 to reinvigorate its own efforts to develop autonomous vehicles. “I feel like we’re brothers from another mother,” the company’s CEO, Travis Kalanick, said.

Uber paid $680 million to make Anthony Levandowski the head of its self-driving car program. The ride-hailing juggernaut acquired his driverless trucking startup, Otto, with its small team of ex-Waymo engineers and proprietary lidar technology, in August 2016 to reinvigorate its own efforts to develop autonomous vehicles. “I feel like we’re brothers from another mother,” the company’s CEO, Travis Kalanick, said.

Nine months and one explosive lawsuit later, Uber is prepared to fire Levandowski to save itself. In a sternly worded letter on May 15, the company demanded Levandowski hand over thousands of files he has been accused of stealing from his former employer, Waymo, and provide a detailed accounting of anyone he ever shared or discussed those files with. Uber sent its letter on the same day a federal judge ruled that Waymo, the self-driving car maker spun out by Google parent Alphabet, had shown “compelling evidence” that Levandowski downloaded 14,000 confidential files before leaving the company in January 2016.

The allegations against Levandowski are the centerpiece of a trade secrets lawsuit that Waymo filed against Uber in February, a dispute that could threaten Uber’s driverless car ambitions not to mention its long term survival. The case is headed for a public trial after William Alsup, the federal judge overseeing it, last week denied Uber’s bid to move the proceedings to private arbitration. Alsup has also referred the matter to the US attorney, a “rare if not unprecedented” step that could lead to criminal charges or even jail time for Uber executives.

Since the litigation began, Levandowski has avoided answering questions about his work at Uber by invoking the Fifth Amendment, which protects against self-incrimination. (“He took the Fifth on virtually everything of substance in his deposition,” Charles Verhoeven, a lawyer for Waymo, complained in a hearing earlier this month.) Uber has similarly refused to turn over certain documents that might incriminate him. On May 15, Alsup ordered Uber and Levandowski to return the files.

The partly granted injunction also bars Levandowski from any work on liar technology—light radar that helps a self-driving car “see”—and instructs Uber to log his lidar-related communications at the company. Alsup told Uber it should do “whatever it can” to ensure that the conditions of the order are met, even if that includes firing Levandowski. “If Uber were to threaten Levandowski with termination for noncompliance, that threat would be backed up by only Uber’s power as a private employer,” he wrote. “Levandowski would remain free to forfeit his private employment to preserve his Fifth Amendment privilege.”

Uber has since told Levandowksi he must comply with the requirements outlined in its letter as a condition of his employment, which could mean waiving protection under the Fifth Amendment. “If you do not agree to comply with all of the requirements set forth herein, or if you fail to comply in a material manner, then Uber will take adverse employment action against you, which may include termination of your employment and such termination would be for Cause,” Uber general counsel Sally Yoo wrote.

“While we have respected your personal liberties, it is our view that the Court’s Order requires us to make these demands of you,” Yoo added. “Footnote 9 of the Order specifically states that ‘in complying with this order, Uber has no excuse under the Fifth Amendment to pull any punches as to Levandowski.’”