Warby Parker, every American hipster’s favorite eyeglasses retailer, is unveiling a new mobile app that allows users to check their prescription at home, without visiting a doctor or an optician’s.

The new app, which rolled out yesterday (May 23), will surely please glasses wearers who dread getting their eyes checked. It’s also alarming optometrists, the doctors who specialize in correcting vision, who depend on a stream of patients making office visits. By offering eye exams online, Warby Parker is giving wearers one more reason to skip their brick-and-mortar competitors—some of whom offer vision exams from in-house optometrists—and buy glasses online.

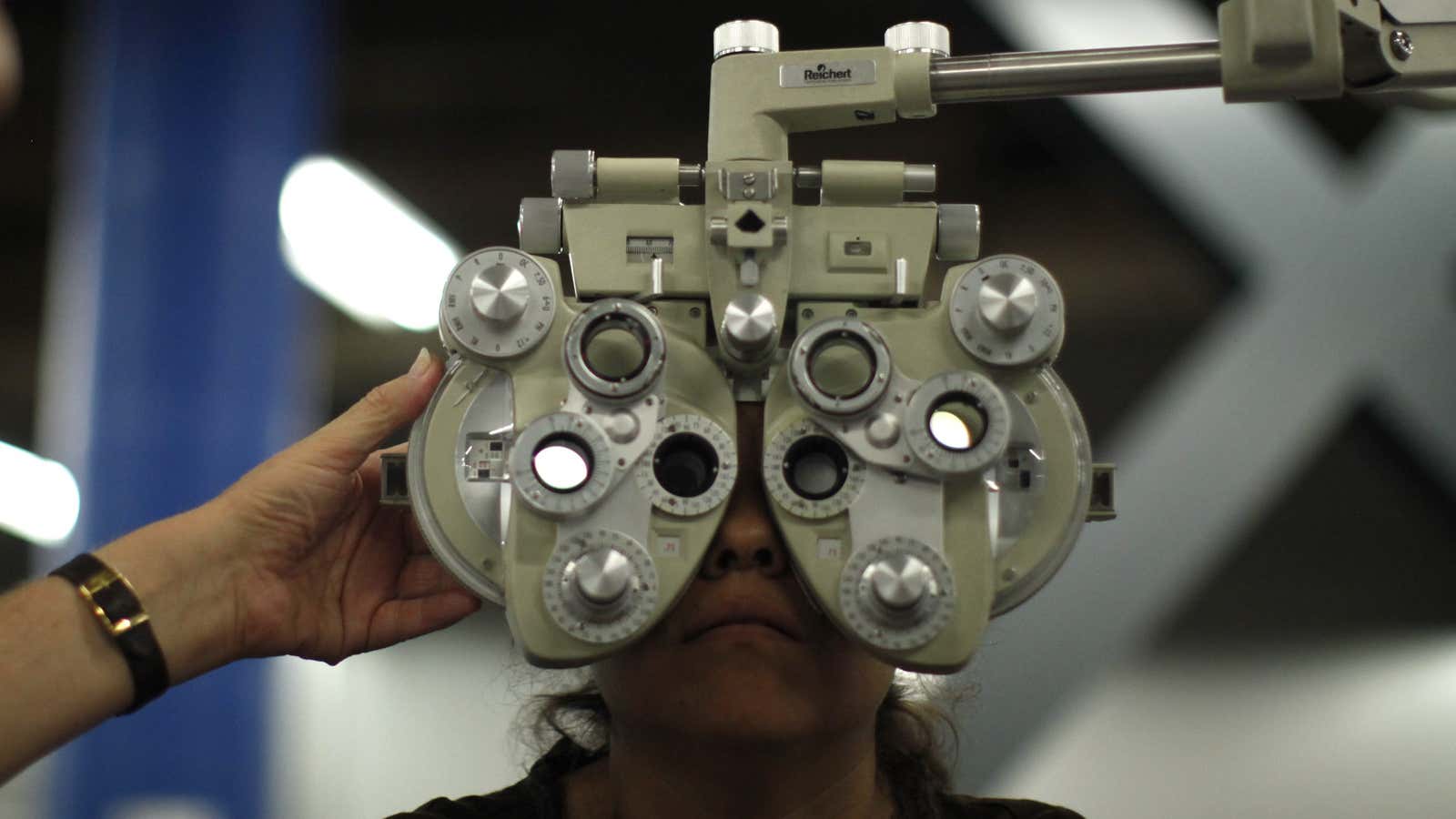

The app helps the user pace off the right distance to conduct the equivalent of the familiar Snellen eye exam (the one with the big E) on a computer screen. A doctor reviews the results, and if there’s no change in eyesight, the user can get an updated prescription. Otherwise, she may be directed to get a more thorough exam from a doctor in person. So far, it’s only available in California, Florida, New York, and Virginia, with more states to come.

With the app, Warby Parker is employing a strategy in some ways similar to that of Uber and Airbnb: using technology to take on a heavily regulated industry with high barriers to entry. Writing prescriptions is the province of medical professionals, who are both burdened and shielded by a slew of licensing requirements that drive up fees. By giving users the tools to conduct their own exam, Warby Parker’s app means far fewer doctors are necessary, which could dramatically reduce cost.

While Uber and Airbnb’s strategy was to roll out its product, develop a market, and only then worry about the regulators, Warby Parker said in an email that it paved the way for its app by first lobbying state lawmakers. It also won’t offer the app in states where the service is banned by law, such as Georgia, Indiana and South Carolina.

Optometrists recognize that technology advances and that online eye exams will only get better and more popular, said Jan Dorman, executive director of the New York optometrist’s industry group. But if Warby Parker is writing prescriptions, it will need to follow the same rules as doctors, such as the federal laws governing patient records and privacy, he said. “We’re not trying to turn back the clock, we’re going to try and level the playing field.” (Warby Parker says it “has worked with legal experts in a number of different fields to ensure that we’re complying with various state and federal laws.”)

There are also concerns that by relying on the app, patients will forgo more through eye exams that can reveal more serious problems like glaucoma, Dorman said.

Even if lobbying from optometrists does saddle Warby Parker with more regulations, it likely won’t dim its enthusiasm for the product. The service is free for now, but it’s a lucrative market. More than 114 million Americans spent $6 billion getting their eyes checked last year, according to the Vision Council, an industry group. That’s a big incentive for Warby Parker to stick it out.