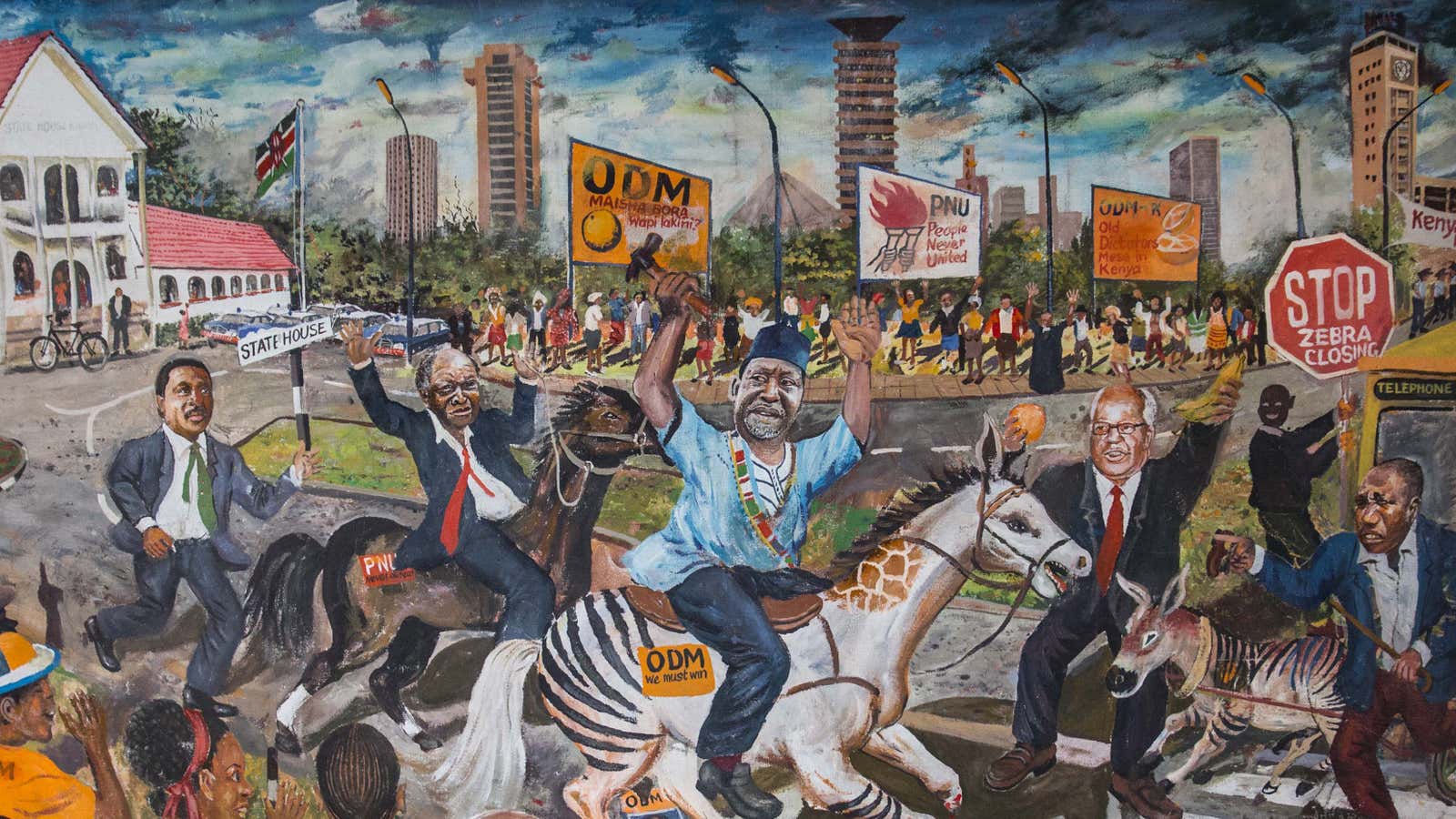

There’s a general misconception that whatever passes for popular art in Kenya are the curios sold to tourists or the murals that hang in restaurants and airport lounges.

But as a new book shows, nothing could be further from the truth. In over 600 pages, Visual Voices presents over 400 pieces from 57 different contemporary artists in Kenya, showcasing a vibrant, edgy, and growing art scene. The artists in the collection use various methods including paintings, sculptures, murals, photography, glassworks, and furniture, besides on-site installation projects.

Issued by the Nairobi-based independent publisher Footprints Press, the book was curated by Susan Wakhungu-Githuku, a prominent Kenyan entrepreneur and a former executive with Coca-Cola in Africa. When she set out to compile the book, Wakhungu-Githuku said she wanted to present as a whole what Kenyan art looked like, and not just the oft-touted images of masks, tribal figurines, and bucolic scenes showing landscapes and wild animals.

The weighty book also displays art’s vital role in documenting the social, political and cultural experiences in Kenya from the 1970s till today. By including young, middle-aged and older artists, the collection shows the changing tastes, styles, and narratives—and by extension, how the conversation about art and its function has shifted with time. The surrealist swirling dreamscapes, the semi-impressionistic paintings, and the sculptures made out of discarded woods and sheets of scrap metal all combine to speak to an artistic sophistication that has evolved consistently and upwardly over the decades.

Over the last few years, Kenya has cashed in on the “art boom” that Africa has been experiencing, especially in major cities like Lagos and Cape Town. And as the global art world wrestles with just how disruptive art fairs have become the traditional business model of galleries marketing art and artists, in Africa, they’re opening up a new market. The international interest is evident in the rising number of visitors, sponsors, and collectors attending art fairs like Art X Lagos or museums the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa.

In Kenya, the surge in interest has come as the political space has opened up to allow for freedom of expression. There’s also the availability of workshops and training programs in centers like Kuona Trust and Dust Depo, which give artists the chance to develop their skills and experiment with new concepts. Young artists, mostly in urban areas, are also working in multiple mediums to explore issues related to their childhood memories, complex social interactions besides racial, ethnic, and religious identities.

The growing appetite for art in the country is also manifested in the growing lists of art acquisitions; Kenya hosted its first major auction in late 2013. Given all these reasons, Wakhungu-Githuku says it is “an exciting time” for Kenyan contemporary art which might “be well at an inflection point.”

The artists featured in Voices include Anthony Okello, whose Masquerade series that explored issues of human and racial identity, is also the book’s cover. There’s also Joseph Bertiers, whose pieces use humor and physical interpretation to document daily events. Rahab Tani and Fred Abuga’s highly vivid and idiosyncratic pieces are also included, both of whom depict a true reflection of society by focusing on people going about their daily lives.

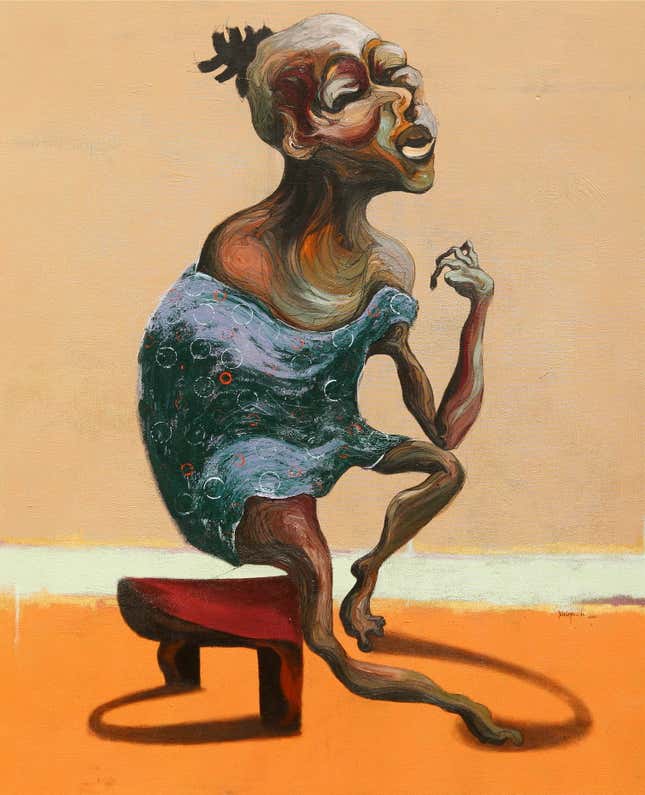

Boniface Maina, one of Kenya’s rising artists, also features acrylic canvasses that defy emotion and arouse thought, anger—and in some cases, confusion. Alex Mbevo, whose work resembles realistic photo projects, is the first artist presented in the book. Mbevo’s oil on canvas paintings capture poverty, droughts, and urban problems, and his Bike Series, capture the joy of children on bicycles.

Michael Soi’s futuristic The Three Musketeers and Peter Ngugi’s Barracuda also present visual masterpieces that are both futuristic and complex. Paul Onditi also reintroduces “Smokey,” a character that appears in various of his paintings and through which he interprets the vagaries of the human condition. Veterans like painter Tabitha wa Thuku and the sculptor and painter Sudan-born Eltayeb Dawelbait are also featured in the collection.

In the introduction to the book, Wakhungu-Githuku writes that she sees the pieces as “voiceless conversations that hopefully will demand countless encores.” Art in Kenya, she argues “is currently galloping and that despite strong influences here and there, in the absence of a truly dominant aesthetic, artists are exercising latitude, freely mixing genres, debunking traditional templates, eschewing predictable cages and experimenting with abandon.”