Over three thousand years ago, a man named Paneb was one of the most accomplished workmen in a town of artisans who chiseled the pharaohs’ tombs. Yet, his corruption and treatment of women made him insufferable and may have cost him his job. It is one of the earliest known cases of powerful men brought down by charges of sexual misconduct.

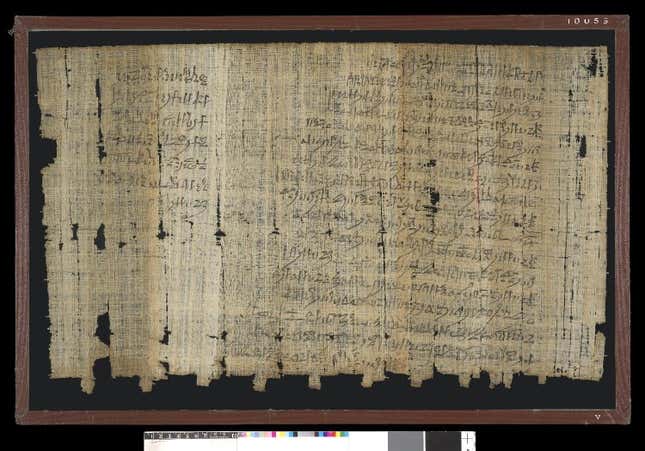

The story of Paneb isn’t new and was revisited recently by Narratively. Paneb’s been dubbed a “bad boy”of ancient Egypt, but reassessing the story in the age of #MeToo changes this glib description of ancient “villain.” The account of his misconduct was recorded on the Papyrus Salt 124, in the possession of the British Museum since the early 19th century when Egyptologist Henry Salt brought it from Egypt.

The papyrus, dating back to around 1200 BCE, is a written complaint by a man name Amennakht and addressed to the Vizier Hori about the conduct of Paneb, the chief workman in Deir el Medina, a community of artisans who built the tombs of Thebes. Paneb is believed to have stolen what was meant to be an inherited position by bribing the vizier at the time.

The earliest translation of this story dates back to 1870, but a more detailed translation (PDF, paywall) by Jaroslav Černý in 1929 gives a laundry list of Paneb’s bad behavior. It focuses on how Paneb stole Amennakht’s job and lists the various items he raided from tombs.

He is accused of stripping a woman named Yeyemwaw, throwing her against a wall and violating her. Lower on the charge sheet and listed as a single crime are the string of women he “debauched,” giving some clue to the weight of these crimes in ancient Egyptian society compared to grave-robbing. What’s more, it may have taken a string of these kinds of allegations for it to be taken seriously (sound familiar?). Still, it is remarkable that it was pointed out as a crime in the first place and that all his victims are named.

Previous studies of the Papayrus Salt 124 have not focused on sexual misconduct either, but in the post-Weisntein era calling for zero-tolerance of sexual assault, there is no implicit tolerance for Paneb’s behavior.

“Even more interesting than what’s in the document is what is left out—namely, the question of consent—which raises fascinating questions not just about ancient Egypt but about the modern world as well,” wrote historian Carly Silver.

The use of the phrase “debauched” leaves some ambiguity, as ancient Egyptians considered adultery within marriage unacceptable, while unmarried Egyptians had no similar expectations, explains Silver. The specific account of one woman as a single charge, however, shows the significance of this particular crime.

It is unclear what became of Paneb once the vizier dealt with his case and how much of the current record is based on his accuser Amennakht anger over losing his job. Centuries later it remains a lesson in how society treats powerful men accused of sexual misconduct.